1.2 Organization & Regulation

1.2.1 System Organization

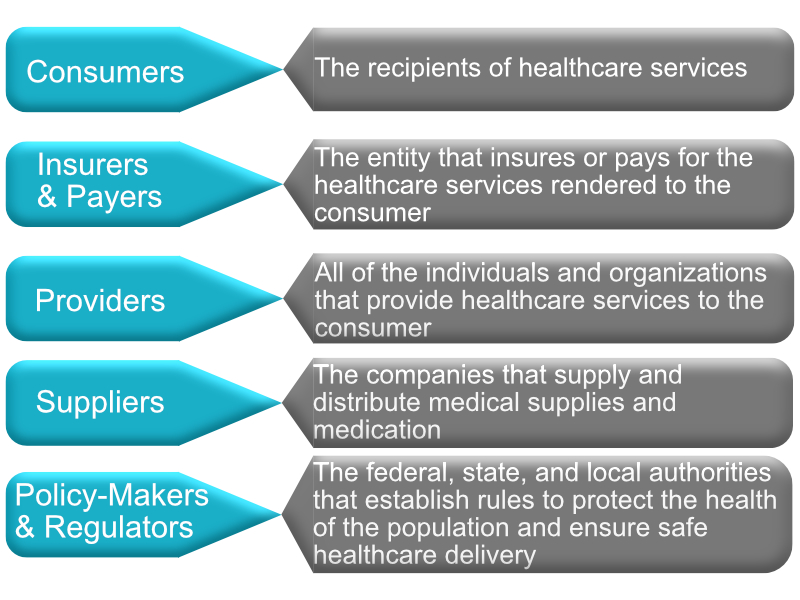

The U.S. healthcare system is not a fully coordinated system. Merriam-Webster’s (2023) dictionary definition of a system is “a regularly interacting or interdependent group of items forming a unified whole.” However, the healthcare system in the U.S. is made up of loosely structured insurance, delivery, payment, and financing networks. According to Lübbeke et al. (2019), five key stakeholders comprise the U.S. healthcare system: the healthcare consumers, insurers and payers, healthcare providers, medical suppliers, and policy-makers and regulators (Fig. 1-2).

Figure 1-2

Components of the U.S. Healthcare System

(Lübbeke et al., 2019)

I. Consumers

Healthcare consumers are the individuals who receive healthcare services (Institute of Medicine, 2010). They are also referred to as patients. Although consumers play a major role in healthcare decision-making, consumers typically depend on the advice of healthcare professionals for medical decisions. However, they may be unaware of the underlying financial obligations. For example, a patient may elect to undergo a medical procedure with an in-network provider, a provider who has negotiated rates with the insurance company to provide specific services at a designated rate (Institute of Medicine, 2010). However, unbeknownst to the consumer, the provider may have an out-of-network staff, for instance, an anesthesiologist, that charges full prices for the services provided, leaving the consumer with an expensive, out-of-pocket bill. Therefore, the consumer must be completely aware of their medical decisions and inquire about fully in-network providers and options.

II. Insurers and Payers

Healthcare financing depends on collecting money for healthcare services and the reimbursement of health providers for the rendered services. The payers include the private sector (insurance companies), the public sector (government and state agencies), and the consumers (out-of-pocket expenses) that share responsibility for the financing functions (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2020). The third-party payer is any organization that pays or insures healthcare expenses for the healthcare consumer. Each service provided to a consumer has a designated fee called a charge (set by the provider) or a rate (set by a third-party payer). Healthcare providers often rely on the patient’s insurance to obtain payment for rendered services which controls how much the provider is paid for his/her services. Financing makes access to healthcare easier, thereby increasing the demand for healthcare services. The U.S. is a multi-payer financing system. Unlike most developed countries with a single-payer system, where national health insurance programs are run by the government and financed through taxes, the U.S. healthcare system is comprised of a complicated mix of public and private, for-profit and non-profit insurance and providers (Donnelly et al., 2019).

III. Providers

Healthcare providers include all individual providers and organizations providing healthcare services to consumers.

Individual providers

Healthcare providers include practitioners, group medical practices, hospitals, nursing homes, and ambulatory facilities (rehabilitation, surgery, imaging, etc.). Because healthcare is a complex set of services provided in various settings, it is not surprising that the human resources needed to provide these services are also varied and complex. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2018a, 2018b) categorizes healthcare personnel into two main categories:

1) Healthcare practitioners and technical occupations: This first category is further divided into a) practitioners with diagnostic and treatment capabilities and b) healthcare technologists and technicians. The practitioners with diagnostic and treatment capabilities include chiropractors, dentists, optometrists, pharmacists, physicians, physician assistants, podiatrists, and registered nurses (RNs), as well as a large grouping of therapists such as occupational, physical, respiratory, speech-language, and others. In their specialized care, these therapists consult and practice with other health professionals. Healthcare technologists and technicians include clinical laboratory technologists and technicians, dental hygienists, licensed practical (vocational) nurses (LPNs), and medical record technicians. The distinction between technologist and technician involves the level of education, which is longer for technologists, and work roles, which are more complex and analytical for technologists. In addition, technologists may supervise the work of technicians.

2) Healthcare support occupations: The category of healthcare support occupations includes several types of aides (e.g., nursing, psychiatric, and home health aides) and dental assistants.

Definition: Aides are “individuals that provide routine care and assistance to patients under the direct supervision of other health care professionals and/or perform routine maintenance and general assistance in health care facilities and laboratories” (National Center for Educational Statistics, 2010).

Review webpage (National Library of Medicine, n.d.): Types of Healthcare Providers

Review webpage (National Library of Medicine, 2017): Health Occupations

Organizations

The physical facilities for healthcare in the U.S. can be placed into several categories. Primary and ambulatory care facilities include doctors’ and dentists’ offices, and community and public health buildings. Hospitals and ambulatory surgical centers are two important types of specialized ambulatory and inpatient care facilities. Institutional forms of long-term care facilities include nursing homes, while non-institutional forms include home healthcare agencies, hospices, and end-stage renal facilities. There are several other types of facilities in each of these categories. Healthcare facilities may be under public or private ownership. They may be licensed by state governments, certified by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services for the Medicare (CMS) program, and/or accredited by private agencies. Hospitals and nursing homes, for example, are licensed by each state and may receive certification from the CMS and accreditation by the Joint Commission (formerly the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations), a private not-for-profit organization. Licensing and certification require that the facility meets standards for the physical structure and the quality and safety of services provided by the facility. In addition, new building construction may be regulated by a state’s certificate of need (CON) law.

Review webpage (Joint Commission, 2023): Healthcare Settings

IV. Suppliers

Healthcare suppliers are the companies that supply and distribute medical supplies and medicine, including pharmaceutical and medical equipment companies. Healthcare suppliers play a major role in the healthcare system by providing medical supplies, such as wheelchairs, CPAP machines, oxygen, and medication that people need to live a high-quality life. Insurance companies often cover a large portion of the cost of medical supplies and prescriptions.

V. Policy-Makers and Regulators

The delivery of healthcare services is regulated by the federal, state, and local authorities that establish rules to protect the population’s health. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services provide government-subsidized medical coverage and set reimbursement standards that regulate how healthcare services are organized and delivered to ensure the safety, security, and quality of healthcare services (CMS, 2022). The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services is the government agency responsible for protecting patient privacy, combating fraudulent claims, and ensuring healthcare agencies comply with federal laws (Straube, 2013; DHHS, 2013). State medical boards are the agencies that license medical doctors and ensure medical professionals are competent, properly trained, and adhere to the highest standards of excellence (Carlson & Thompson, 2005). Agencies such as the Joint Commission monitor the quality of services by implementing a system that examines healthcare organizations based on compliance and improvement activities (Joint Commission, 2022a; Wadhwa & Huynh, 2022). The Joint Commission grants compliant healthcare organizations a seal of approval after the organization earns accreditation. These seals are important to healthcare organizations because Medicare considers these seals when determining reimbursement (Joint Commission, 2022a; Wadhwa & Huynh, 2022). The government is central to all aspects of healthcare delivery, including licensing requirements, standards for participation in government-run programs, security and privacy laws regarding patient health information, and setting standards for patient safety and quality transparency standards of healthcare organizations (Straube, 2013).

1.2.2 System Regulation

Regulation in the U.S. healthcare system may be imposed by private or public entities at the federal, state, local county, and city levels as a response to “the constant need to balance the objectives of enhancing quality, expanding access, and controlling the cost of care” (Field, 2007). As a result, all actors in the healthcare system are subject to regulation, often from multiple government and nongovernment agencies.

I. Regulation of Third-Party Payers

In the U.S., the regulation and governance of private insurers, or third-party payers is shared by federal and state agencies. The current regulatory environment facing third-party payers has arisen primarily from three pieces of legislation: the McCarran-Ferguson Act, The Employee Retirement Income Security Act, and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA). In reaction to a Supreme Court ruling that the business of insurance was interstate commerce and therefore subject to Congressional regulation and federal antitrust laws, the McCarran-Ferguson Act was passed by Congress in 1945 to counteract the Supreme Court decision and reaffirm the power of states to regulate and tax insurance products of third-party payers (U.S. Government Accountability Office [GAO], 2005). This Act essentially reserved authority to regulate third-party payers for state authorities. Many, if not all, states have provisions in their codes to prohibit insurers from engaging in unfair or deceptive acts or practices in their states (GAO, 2005). However, in 2011, as part of the ACA, the CMS – a federal agency – took over the review of health insurance rates increasing in excess of 10% annually from some states due to a lack of or inadequate state regulation of health insurance products sold to individuals and small businesses (CMS, 2010).

The other key piece of legislation regarding the regulation of third-party payers is The Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA), enacted by Congress in 1974 (Congressional Research Service Report for Congress, 2009). ERISA is a federal law that sets minimum standards for most voluntarily established retirement and health plans in private industry to provide protection for individuals in these plans (U.S. Department of Labor, n.d.). ERISA regulations fall under the Department of Labor in the federal government, in contrast to McCarran-Ferguson’s focus on state-level regulation. They set minimum standards to protect individuals participating in most voluntarily established pension and health insurance private sector employee benefit plans (i.e., self-insured employers). ERISA does not require private employers to offer health insurance but governs the administration of these plans if employers self-insure, and defines how disputes are handled. Group health plans established by government or church organizations and plans that only apply to workers’ compensation or disability, or unemployment are not governed by ERISA (U.S. Department of Labor, 2019).

The ACA was initiated in 2010 to reform the U.S. healthcare system and expand health insurance to cover the large number of uninsured individuals. The ACA required all U.S. citizens and legal residents be covered by public or private insurance. Failure to do so would require the uninsured to pay a tax, with some exemptions, such as religious beliefs and financial hardships. However, the individual mandate was removed in 2019, and the tax penalty has been repealed. The ACA also requires insurance plans to cover young adults under their parent’s policy until they are 26 years of age (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2016). There are three key tenets of the ACA: 1) Enables states to expand Medicaid coverage to individuals with incomes 138% below the federal poverty level; 2) Establishes state-based insurance marketplaces to keep prices competitively low; 3) Emphasizes prevention and wellness efforts.

II. Regulation of Providers

Healthcare professionals

Physicians, nurses, and many allied health professionals are accredited by licensing boards in the state in which they practice. State licensing boards issue new licenses to healthcare professionals with the requisite educational credentials, renew licenses and enforce basic standards of practice through their power to suspend or revoke licenses to practice (Field, 2007). In addition to state-level regulation, the CMS regulates physicians at the federal level by imposing criteria for reimbursing providers for services rendered. For example, Medicare requires physicians to meet certain requirements, many overlapping with state-licensing requirements (CMS, 2011a). Since Medicare patients make up a significant portion of many physicians’ payer mix, the requirements for reimbursement serve as a form of provider regulation.

Furthermore, the CMS does not reimburse physicians for self-referred services. The Ethics in Patient Referrals Act (also known as the Stark Law), was passed in 1989 to prohibit payment to physicians for referrals to services in which they or their family members have a financial interest (CMS, 2011b). Managed care organizations also regulate physicians. Managed care organizations are integrated and coordinated to provide care to a specific patient population. Managed care organizations regulate physician behavior through various mechanisms for controlling costs (e.g., capitation, gatekeeping, pre-authorization) and improving quality (e.g., disease management). Managed care organizations also give credentials to physicians in their network, again ensuring providers can demonstrate basic requirements to practice similar to those required by state licensing boards and the CMS.

Hospitals at which physicians practice also regulate physicians through credentialing. Hospitals oversee physician practice through review boards and can discipline physicians for substandard care by requiring additional medical education or supervision by colleagues, or suspending clinical privileges (Field, 2007). Hospital regulation in the U.S. occurs primarily via certification requirements (e.g., The Joint Commission, Det Norske Veritas Healthcare, the Center for Improvement in Healthcare Quality, and the Healthcare Facilities Accreditation Program), federal law on who must be treated at hospitals, and eligibility for reimbursement criteria imposed by the CMS. Some of the most important hospital oversight results from the self-policing role of accreditation by the Joint Commission. This organization is a nongovernmental regulatory body that collaborates with more than 4000 hospitals in the U.S. (Joint Commission, 2022b). Auditors from the Joint Commission survey hospitals unannounced and evaluate compliance with Joint Commission standards by tracing care delivered to patients, acquiring documentation from the hospital, tracking hospital quality measures, and on-site observation.

The Emergency Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA), passed in 1986, requires that all hospitals participating in Medicare provide a medical screening examination when a request is made for examination or treatment for an emergency medical condition, including active labor, regardless of an individual’s ability to pay (CMS, 2011c). After screening, hospitals are required to stabilize patients with emergency medical conditions or, if they cannot stabilize a patient (e.g., due to capacity constraints), transfer the patient for stabilization. As a result of EMTALA, the emergency department has become an access point commonly used by patients with limited access to primary care, such as the uninsured.

In 1946 Congress enacted the Hospital Survey and Construction Act, permitting State-Federal cooperation in providing needed community health facilities. This law, sponsored by Senators Lister Hill and Harold H. Burton, came to be known as the Hill-Burton Act. It authorized matching Federal grants, ranging from one-third to two-thirds of the total cost of construction and equipment, to public and nonprofit private health facilities (U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, 1965). As a result of the Hill-Burton Act, many U.S. hospitals are required to take Medicare and Medicaid patients. They are, therefore, subject to CMS eligibility criteria for reimbursement through conditions of participation (CoPs) and conditions for coverage (CoCs). As a result, the CMS is able to regulate hospital care by ensuring facilities receiving CMS reimbursement meet minimum quality and safety standards (CMS, 2011d). These conditions for participation and coverage also apply to many other health services delivery organizations, such as nursing homes and psychiatric hospitals. The conditions laid out by the CMS cover most of the essential components of hospitals or other health services facilities, including requirements for staffing, patients’ rights, and medical records.

III. Regulation of Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices

Pharmaceuticals in the U.S. are primarily regulated at the federal level by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The present-day FDA evolved from legislation adopted in 1906 in response to public health epidemics resulting from unsafe foods and drugs. The FDA approval process for new drugs or biological products consists of animal testing, and then four phases of testing in humans, three of which are completed before the drug can go on the market. The fourth phase of testing continues after the drug has been released. The clinical trials stage often takes several years, with costs largely borne by the drug manufacturer. However, for biological products, the ACA included a new statutory provision to expedite the FDA approval process for drugs that are ‘biosimilar’ with an FDA-approved biological product (FDA, 2012). The use of biosimilars is estimated to save the U.S. healthcare system approximately $44 billion between 2014 and 2024 (Boccia et al., 2017). The FDA also regulates pharmaceutical advertising through its labeling requirements and ability to penalize drug companies conducting advertising that it deems excessive or misleading. From the 1990s, drug companies started advertising directly to consumers. Among the high-income countries, the U.S. is one of the few to permit direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription-only drugs (Magrini, 2007). While no laws in the U.S. prevent drug companies from advertising prescription drugs directly to consumers, the FDA can prosecute manufacturers for false or misleading advertising.

In addition to regulating pharmaceuticals, the FDA is the principal regulator of medical devices and radiation-emitting products used in the U.S. The FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) regulates firms that manufacture, repackage, relabel, and/or import medical devices and radiation-emitting electronic products (medical and non-medical), such as lasers, X-ray systems, ultrasound equipment, microwave ovens, and color televisions (FDA, 2011a). The Medical Device Amendments of 1976 to the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act established three regulatory classes for medical devices. The three classes are based on the degree of control necessary to assure the various types of devices are safe and effective (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2017).

Class I – These devices present minimal potential for harm to the user and are often simpler in design than Class II or Class III devices. Forty-seven percent (47%) of all medical devices fall under this category. Examples include enema kits and elastic bandages. The majority of Class I devices (i.e., 95%) are exempt from FDA notification before marketing. Examples of exempt devices are manual stethoscopes, mercury thermometers and bedpans. If a device falls into a generic category of exempted Class I devices, a premarket notification application and FDA clearance is not required before marketing the device in the U.S. However, the manufacturer is required to register their establishment and list their generic product with FDA.

Class II – Most medical devices are considered Class II devices. Examples of Class II devices include powered wheelchairs and some pregnancy test kits. Forty-three percent (43%) of medical devices fall under this category. Section 510(k) of the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act requires those device manufacturers who must register to notify FDA their intent to market a medical device. This is known as Premarket Notification (PMN). Under PMN, before a manufacturer can market a medical device in the United States, they must demonstrate to FDA’s satisfaction that it is substantially equivalent (as safe and effective) to a device already on the market. If FDA rules the device is substantially equivalent, the manufacturer can market the device. Most Class II devices require Premarket Notification.

Class III – These devices usually sustain or support life, are implanted, or present potential unreasonable risk of illness or injury. Examples of Class III devices include implantable pacemakers and breast implants. Ten percent (10%) of medical devices fall under this category. A primary safeguard in the way FDA regulates medical devices is the requirement that manufacturers must submit to FDA a Premarket Approval (PMA) application if they wish to market any new products that contain new materials or differ in design from products already on the market. A PMA submission must provide valid scientific evidence collected from human clinical trials showing the device is safe and effective for its intended use. Most Class III devices require Premarket Approval from the FDA.

The FDA also monitors reports of adverse events and other problems with medical devices and alerts health professionals and the public when needed to ensure the proper use of devices and the health and safety of patients (FDA, 2011b).

IV. Regulation of Patient Privacy and Human Subjects

Regulations regarding the privacy of health information in the U.S. were initiated in the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) privacy and security rules passed by Congress in 1996. The privacy component of the law provides federal protection for personal health information and gives patients rights with respect to that information (DHHS, 2011). The security portion has administrative, physical, and technical safeguards to ensure the confidentiality of patient information. The Office of Civil Rights enforces HIPAA privacy and security rules under the DHHS. The Patient Safety and Quality Improvement Act of 2005 (PSQIA) establishes a voluntary reporting system to enhance the data available to assess and resolve patient safety and healthcare quality issues. PSQIA provides federal privilege and confidentiality protections for patient safety information to encourage the reporting and analysis of medical errors (DHHS, 2011). The PSQIA requires disclosure of medical errors to affected patients while protecting those who report the errors by not allowing voluntary admissions by providers to be used against them in a court of law (Howard et al., 2010).

The Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP) within the DHHS regulates the protection of human subjects used in clinical and non-clinical research. Its purview “applies to all research involving human subjects conducted, supported or otherwise subject to regulation by any federal department or agency, and includes research conducted by federal civilian employees or military personnel and research conducted, supported, or otherwise subject to regulation by the federal government outside the United States” (OHRP, 2011). Since the vast majority of the research on health in the U.S. is funded by various government grant mechanisms or regulated by some federal agency, OHRP regulations regarding human subjects research affect much of the research involving people. In addition to the OHRP, many individual research institutions, such as universities, also have departments that verify whether human subjects research is warranted and will be conducted safely, effectively, and with dignity.