4.3 Quality of Care

Sections:

4.3.1 Definition and Domains of Quality

A definition of quality that has historically guided the measurement of quality initiatives in healthcare systems is based on the framework for improvement created by the Institute of Medicine (IOM). The IOM changed its name to the National Academy of Medicine (NAM) in 2015. The National Academy of Medicine further defines quality as having the following properties or domains (AHRQ, 2020b):

- Safe: Avoiding harm to patients from the care intended to help them.

- Effective: Providing services based on scientific knowledge to all who could benefit and refraining from providing services to those not likely to benefit (i.e., avoiding underuse and misuse).

- Patient-centered: Providing care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions.

- Timely: Reducing waits and sometimes harmful delays for both those who receive and those who provide care.

- Efficient: Avoiding waste, including waste of equipment, supplies, ideas, and energy.

- Equitable: Providing care that does not vary in quality because of personal characteristics such as gender, ethnicity, geographic location, and socioeconomic status.

This framework continues to guide quality improvement initiatives across America’s healthcare system. The evidence-based practice (EBP) movement began with the public acknowledgment of unacceptable patient outcomes resulting from a gap between research findings and actual healthcare practices. For EBP to be successfully adopted and sustained, it must be adopted by healthcare team members, system leaders, and policymakers. Regulations and recognitions are also necessary to promote the adoption of EBP. For example, the Magnet Recognition Program promotes nursing as a leader in catalyzing the adoption of EBP and using it as a marker of excellence (Stevens, 2013).

4.3.2 Quality Improvement Methods

Healthcare differs from other industries that rely on labor in that it is more difficult to achieve increased productivity. Effective performance improvement methodologies in healthcare have been slow to adapt. Healthcare providers are increasingly challenged to provide improved patient services at a faster pace. The traditional physician-centric model of healthcare must change. The following are four widely utilized improvement methodologies to improve processes and quality: 1) Plan-Do-Study-Act, 2) Six Sigma, 3) Lean, and 4) Lean Six Sigma.

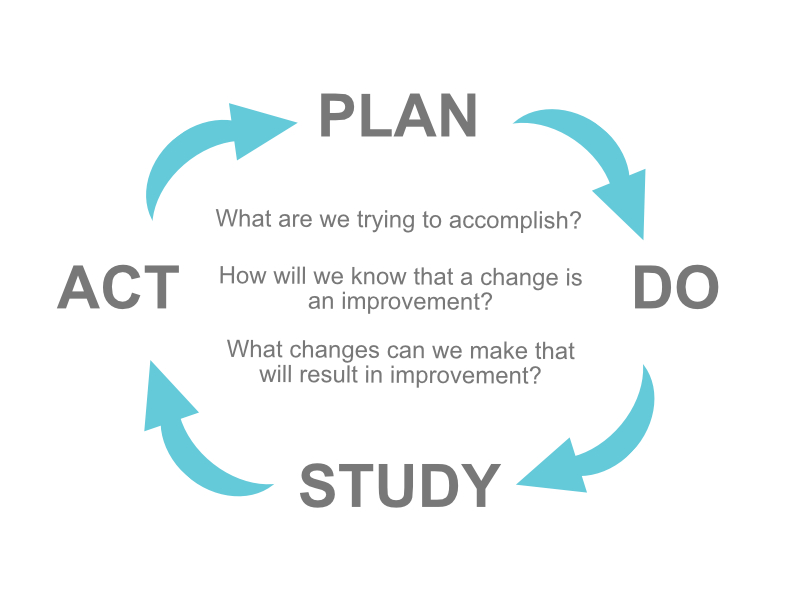

I. Plan-Do-Study-Act

One of the most commonly used improvement methods is the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle (Fig. 4-3). PDSA was developed in 1986 as a more effective alternative to a precursor method known as Plan-Do-Study-Check. Since quality improvement projects are typically team-based, PDSA places great emphasis on including the right people for success (Langley et al., 2009). Planning can be the most important part of a successful project. Change should be monitored and adjusted as needed. The cycle of PDSA allows for refinement of the change to implementation on a broader scale after successful changes have been identified (Langley et al., 2009). The following two documents review the steps associated with each phase of the PDSA cycle and examples in a healthcare setting:

- The PDSA Cycle Step by Step (Administration for Children & Families, 2018)

- Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) Directions and Examples (AHRQ, 2020c)

Figure 4-3

Plan-Do-Study-Act Method for Quality Improvement

(AHRQ, 2020c)

II. Six Sigma

Six Sigma is another model for quality improvement using a measurement-based strategy for process improvement and problem reduction applied to improvement projects. The term Six Sigma derives from the Greek letter σ (sigma), used to denote standard deviation from the mean or how far something deviates from perfection. By definition, six sigma is the equivalent of 3.4 defects or errors per million (Seecof, 2013). Six Sigma models include DMAIC (define, measure, analyze, improve, control) and DMADV (define, measure, analyze, design, verify). DMAIC is used to make incremental improvements to existing processes, whereas DMADV is used to develop new processes at Six Sigma quality levels (Seecof, 2013). DMAIC is a formalized problem-solving method designed to improve the effectiveness and ultimate efficiency of the organization (Table 1).

Table 1 The DMAIC Method

| What is DMAIC? | |

|---|---|

| Define: What is the problem? |

Who wants the project, and why The scope of the project/improvement Key team members and resources for the project Critical milestones and stakeholder review Budget allocation |

| Measure: How big is the problem? |

Ensure measurement system reliability Prepare a data collection plan How many data points need to be collected How much time will data collection take What is the sampling strategy Who will collect data, and how will it be stored |

| Analyze: What is causing the problem? |

Use a variety of tools Choose the tools that best fit the improvement strategy |

| Improve: What will solve the problem? |

Gain insight into the problem's causes Control/eliminate those causes to achieve better performance |

| Control: How can the improvement be sustained? |

The best controls are those that require no monitoring |

(Ahmed, 2019)

Having arrived at one or more solutions, it is time to implement new processes or systems and monitor to ensure consistent achievement. The “control” stage is the release of responsibility from the project. Once this stage is achieved, some organizations may implement the support of a Six Sigma project team to ensure the sustainability of the improvement in the future.

III. Lean

Lean concepts can be introduced as a tool to reduce waste, including unnecessary work due to errors, poor organization, or communication. The core principle of Lean is to reduce and eliminate non-value-adding activities and waste. According to Simon (2013), the three key pillars of Lean in healthcare include (Fig. 4-4):

- Delivering value (from the patient’s perspective)

- Eliminating waste (from the patient’s perspective)

- Continuously improving processes to better serve patients

Figure 4-4

The Three Key Pillars of Lean in Healthcare

(Simon, 2013)

Lean methodology designates eight areas of waste: defects, overproduction, waiting, transportation, inventory, motion, extra-processing, and non-utilized or underutilized talent (American Society for Quality, 2023a). Some examples that may seem insignificant include the following:

- Reducing inventory, especially medical supplies that have expiration dates

- Reducing or maximizing the use of space

- Reducing wait times

- Reductions of defects, medical errors, and mistakes

- Increasing the overall productivity and utilization of employees

Value stream mapping is a technique organizations use to create a visual guide of all the components necessary to deliver a product or service, aiming to analyze and optimize the entire process. According to the American Society for Quality (2023b):

Value stream mapping is a workplace efficiency tool designed to combine material processing steps with information flow, along with other important related data. VSM is an essential Lean tool for an organization wanting to plan, implement, and improve while on its Lean journey. VSM helps users create a solid implementation plan to maximize their available resources and help ensure that materials and time are used efficiently.

Using Lean concepts can improve the quality of patient care. To illustrate, review these Lean implementation case studies (Purdue University, 2022):

Rural hospital uses Lean Daily Improvement to increase patient feedback

Primary care practice improves EHR efficiency for better physician-patient interaction

Also, consider these various scenarios:

- Providers walk down the hall to a printer. This effort is wasted motion and time. A more efficient solution may be to install a printer at both ends of the clinic.

- The new electronic health record (EHR) system is not optimized, and physicians must scroll through hundreds of diagnosis and billing codes. Consider condensing the list of available codes to the top five or ten. This small change could save them a significant amount of time and frustration.

- A nurse performing clerical duties may need to redistribute some tasks to non-licensed employees, thus optimizing their nursing skills on more appropriate tasks.

- One floor is short-staffed, while another floor has a low patient volume. Nursing staff may need to be redistributed to help balance the workload on the other floors.

IV. Lean Six Sigma

Lean Six Sigma is a philosophy of improvement that values defect prevention over defect detection (American Society for Quality, 2023a). It drives patient satisfaction and bottom-line results by reducing variation, waste, and cycle time while simultaneously promoting process standardization and flow. The combination, Lean Six Sigma, became mainstream in healthcare by the 2000s.

Using the two initiatives together has resulted in superior results to what either program could have achieved alone. Lean creates value by minimizing waste, while Six Sigma reduces defects through effective problem-solving. In addition, Lean can accelerate the Six Sigma process, making it more efficient.

Preparing a healthcare team for change using Lean and Six Sigma requires the organization to set clear goals, communicate, establish a Lean mindset by cultivating shared leadership among the team, start small, and find a change agent. Often, the best change agent can be the provider or employee with the strongest opposition. Gaining their trust, respect, and buy-in can be the biggest asset. For example, several senior physicians in a medical practice opposed the rollout of a new EHR system. Getting the strongest opposition on board by explaining that the success of this rollout would weigh heavily on the administrator’s job performance was critical. His desire to ensure the administrator’s success in the eyes of leadership was enough to get him on board. He became the physician champion by gaining the buy-in from the rest of the providers. This step was the lynchpin in the project’s success.

4.3.3 Measures of Quality

Examples of quality measures in healthcare include the:

- Magnet Recognition Program

- Value-based reimbursement models

- CMS quality initiatives

- Accreditation review process

- Core measures

- Patient safety goals

I. Magnet Recognition Program

The Magnet Recognition Program is an American Nurses Credentialing Center award that recognizes organizational commitment to nursing excellence. “The Magnet Recognition Program designates organizations worldwide where nursing leaders successfully align their nursing strategic goals to improve the organization’s patient outcomes” (American Nurses Association, n.d.). To nurses, Magnet Recognition means education and development are available throughout their career. To patients, it means quality care is delivered by nurses who are supported to be the best they can be.

II. Reimbursement Models

Quality healthcare is also defined by the value-based reimbursement models used by Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurance companies paying for healthcare services. Reimbursement models use financial incentives to reward quality healthcare and positive patient outcomes. For example, Medicare no longer reimburses hospitals to treat patients who acquire certain preventable conditions during their hospital stay, such as pressure injuries or urinary tract infections associated with the use of catheters (James, 2012). These reimbursement models directly impact the evidence-based care nurses provide at the bedside and the associated documentation of assessments, interventions, and nursing care plans to ensure quality performance criteria are met.

There are five original value-based programs; their goal is to link provider performance of quality measures to provider payment (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2022a):

- End-Stage Renal Disease Quality Incentive Program – The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) administers the End-Stage Renal Disease Quality Incentive Program to promote high-quality services in renal dialysis facilities. The first of its kind in Medicare, this program changes the way CMS pays for the treatment of patients who receive dialysis by linking a portion of payment directly to facilities’ performance on quality of care measures.

- Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program – The Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program (VBP) rewards acute care hospitals with incentive payments for the quality of care provided in the inpatient hospital setting. The Hospital VBP Program encourages hospitals to improve the quality, efficiency, patient experience and safety of care that Medicare beneficiaries receive during acute care inpatient stays.

- Hospital Readmission Reduction Program – The Hospital Readmission Reduction Program is a Medicare value-based purchasing program that encourages hospitals to improve communication and care coordination to better engage patients and caregivers in discharge plans and, in turn, reduce avoidable readmissions.

- Value Modifier Program (also called the Physician Value-Based Modifier) – The Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) under the Quality Payment Program replaced the Physician Feedback/Value-Based Payment Modifier Program on January 1, 2019. The Physician Feedback Program provided comparative performance information to solo practitioners and medical practice groups, as part of Medicare’s efforts to improve the quality and efficiency of medical care furnished to Medicare beneficiaries.

- Hospital Acquired Conditions Reduction Program – The Hospital Acquired Conditions Reduction Program encourages hospitals to improve patients’ safety and reduce the number of conditions people experience from their time in a hospital, such as pressure sores and hip fractures after surgery. This Program encourages hospitals to improve patients’ safety and implement best practices to reduce their rates of infections associated with health care.

Other value-based programs include (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2022a):

- Skilled Nursing Facility Value-Based Purchasing – The CMS awards incentive payments to skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) through the Skilled Nursing Facility Value-Based Purchasing (SNF VBP) Program to encourage SNFs to improve the quality of care they provide to Medicare beneficiaries. For the Fiscal Year 2024 Program year, performance in the SNF VBP Program is based on a single measure of all-cause hospital readmissions.

- Home Health Value-Based Purchasing – The CMS Innovation Center implemented the Home Health Value-Based Purchasing (HHVBP) Model (i.e., the original Model) in nine (9) states on January 1, 2016. The specific goals of the original Home Health Value-Based Purchasing (HHVBP) Model were to provide incentives for better quality care with greater efficiency, study new potential quality and efficiency measures for appropriateness in the home health setting, and enhance the current public reporting process. The expanded HHVBP Model began on January 1, 2022 and includes Medicare-certified Home Health Agencies in all fifty (50) states, District of Columbia, and the U.S. territories. Under the expanded HHVBP Model, HHAs receive adjustments to their Medicare fee-for-service payments based on their performance against a set of quality measures, relative to their peers’ performance.

III. CMS Quality Initiatives

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) establishes quality initiatives focusing on several key quality measures of healthcare. These quality measures provide a comprehensive understanding and evaluation of the care an organization delivers, and responses from the patients who received care. These quality measures evaluate many areas of healthcare, including the following (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2022b):

- Health outcomes

- Clinical processes

- Patient safety

- Efficient use of healthcare resources

- Care coordination

- Patient engagement in their own care

- Patient perceptions of their care

These measures of quality focus on providing the care the patient needs when the patient needs it in an affordable, safe, and effective manner. It also means engaging and involving the patient, so they take ownership of their care at home.

IV. Accreditation

Accreditation is a review process that determines if an agency meets the defined standards of quality determined by the accrediting body. The quality standards vary depending on the accrediting organization, but they all share common goals to improve efficiency, equity, and delivery of high-quality care. The main accrediting organizations for healthcare are as follows:

- The Joint Commission

- National Committee for Quality Assurance

- American Medical Accreditation Program

- American Accreditation Healthcare Commission

V. Core Measures

Core measures are national standards of care and treatment processes for common conditions. These processes are proven to reduce complications and lead to better patient outcomes. Core measure compliance reports show how often a hospital successfully provides recommended treatment for certain medical conditions. In the United States, hospitals must report their compliance with core measures to the Joint Commission, CMS, and other agencies (Johns Hopkins Medicine, 2023).

In November 2003, The Joint Commission and CMS began to align common core measures to be identical. This work resulted in the creation of one common set of measures known as the Specifications Manual for National Hospital Inpatient Quality Measures. Both organizations use these core measures to improve the healthcare delivery process. Examples of core measures include guidelines regarding immunizations, tobacco treatment, substance use, hip and knee replacements, cardiac care, strokes, treatment of high blood pressure, and the use of high-risk medications in the elderly. Healthcare providers must be aware of core measures and ensure the care they provide aligns with these recommendations (The Joint Commission, 2023a).

VI. Patient Safety Goals

Patient safety goals are guidelines specifically for organizations accredited by The Joint Commission that focus on healthcare safety problems and ways to solve them. The National Patient Safety Goals (NPSG) were first established in 2003 and are updated annually to address areas of national concern related to patient safety, and promote high-quality care. The NPSG provides guidance for specific healthcare settings, including hospitals, ambulatory clinics, behavioral health, critical access hospitals, home care, laboratory, skilled nursing care, and surgery. Documentation in the electronic medical record is primarily used as evidence that an organization is meeting these goals. The following goals are some examples of NPSG for hospitals (The Joint Commission, 2023b):

- Identify patients correctly

- Improve staff communication

- Use medicines safely

- Use alarms safely

- Prevent infection

- Identify patient safety risks

- Prevent mistakes in surgery