1.3 Health Status

Sections:

1.3.1 Health and Wellness

I. Definitions

While health is the outcome of an interest or a goal, wellness includes the process needed to achieve health. However, there may be social or cultural challenges to supporting wellness and upholding a prevention approach. In addition to cultural challenges, behavior change is complex, and compliance with wellness habits and programs is poor (Reif et al., 2020). Therefore, a culture that empowers employees or patients to make wellness a part of their routine and builds awareness of the multidimensional value of wellness may encourage progress.

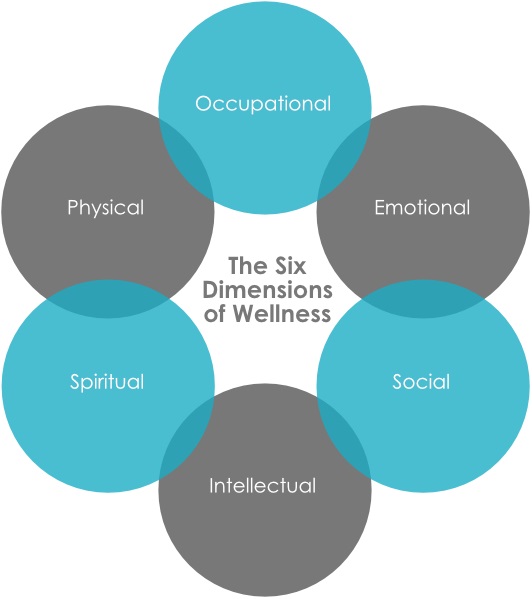

To achieve wellness, a person must be healthy in six interconnected dimensions of wellness (Fig. 1-3): emotional, occupational, physical, social, intellectual, and spiritual (National Wellness Institute [NWI], 2022). Learning about these Six Dimensions of Wellness can help a person choose how to make wellness a part of everyday life. In addition, wellness strategies are practical ways to start developing healthy habits that can positively impact physical and mental health. According to NWI (2022), The six dimensions of wellness are:

1. Emotional: The degree to which one feels positive and enthusiastic about oneself and life. In this dimension, it is important to be aware of and accept one’s feelings & take an optimistic approach to life.

2. Occupational: Satisfaction in one’s work. In this dimension, it is important to seek out a career whichis consistent with one’s personal values, interests, and beliefs. Individuals are encouraged to develop functional, transferable skills through structured involvement opportunities, and to remain active and involved.

3. Physical: A focus and emphasis on movement, fitness, sleep, relaxation, and maintaining a healthy lifestyle, including the consumption of foods and beverages that enhance rather than impair good health.

4. Social: Making contributions to the common welfare of one’s community and thinking of others. In

this dimension, it is important to live in harmony with others and the environment.5. Intellectual: Life-long learning that stretches one’s thinking and challenge one’s mind in both intellectual and creative pursuits, in addition to Identifying potential problems and choosing appropriate courses of action based on available information.

6. Spiritual: Being true to oneself, living each day in a way that is consistent with one’s values and beliefs, going beyond faith and religion to ponder the meaning of life, and be tolerant of the beliefs of others.

Figure 1-3

Six Interconnected Dimensions of Wellness

(NWI, 2022)

Review fact sheet (NWI, n.d.): Six Dimensions of Wellness Model

Then, download and take (NWI, 2022): The NWI_Six-Dimensions-of-Wellness-Self-Assessment_2022

II. Investment in Health

Mortality rate

- Heart disease

- Cancer

- COVID-19

- Accidents (unintentional injuries)

- Stroke (cerebrovascular diseases)

- Chronic lower respiratory diseases

- Alzheimer’s disease

- Diabetes

- Influenza and pneumonia

- Nephritis, nephrotic syndrome, and nephrosis

These ten leading causes accounted for 74.1% of all deaths in the United States (U.S.) in 2020. The following report from the National Center for Health Statistics presents 2020 mortality data on deaths and death rates by demographic and medical characteristics.

Review report (CDC, 2021): NCHS Data Brief – Mortality in the United States, 2020

Productivity

Review infographic (Integrated Benefits Institute, 2019): The Cost of Poor Health

Workplace health programs can increase productivity. In general, healthier employees are more productive (CDC, 2016):

- Healthier employees are less likely to call in sick or use vacation time due to illness.

- Companies that support workplace health have a greater percentage of employees at work every day.

- Because employee health frequently carries over into better health behavior that impacts both the employee and their family (such as nutritious meals cooked at home or increased physical activity with the family), employees may miss less work caring for ill family members.

- Similarly, workplace health programs can reduce presenteeism — the measurable extent to which health symptoms, conditions, and diseases adversely affect the productivity of individuals who choose to remain at work.

The cost savings of providing a workplace health program can be measured against absenteeism among employees, reduced overtime to cover absent employees, and costs to train replacement employees (CDC, 2016).

III. Health Indicators

“Health indicators attempt to describe and monitor a population’s health status. The reason indicators are used in public health is to drive decision-making for health. The ultimate objective is to improve the health of the population and reduce unjust and preventable inequalities” (Pan American Health Organization, 2018). Three common health indicators include life expectancy, deaths from cancer, and infant mortality.

Life expectancy

Overall, compared to other high-income countries, life expectancy in the U.S. is lower and mortality is higher. The following report provides data and trends on the performance of the U.S. compared to health systems in OECD countries and key emerging economies:

Review report (OECD, 2021): Health at a Glance 2021: OECD Indicators – Highlights for the United States

However, there is disagreement over whether or not this relatively poor performance on mortality is due to structural problems with the healthcare system. According to the CDC (2022a):

Life expectancy at birth in the United States declined nearly a year from 2020 to 2021, according to new provisional data from the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics. That decline – 77.0 to 76.1 years – took U.S. life expectancy at birth to its lowest level since 1996. The 0.9 year drop in life expectancy in 2021, along with a 1.8 year drop in 2020, was the biggest two-year decline in life expectancy since 1921-1923. More specifically:

- In 2021, life expectancy at birth was 76.1 years, declining by 0.9 years from 77.0 in 2020.

- Life expectancy at birth for males in 2021 was 73.2 years, representing a decline of 1.0 years from 74.2 years in 2020.

- For females, life expectancy declined to 79.1 years, decreasing by 0.8 years from 79.9 years in 2020.

- Excess deaths due to COVID-19 and other causes in 2020 and 2021 led to an overall decline in life expectancy between 2019 and 2021 of 2.7 years for the total population, 3.1 years for males, and 2.3 years for females.

- The declines in life expectancy since 2019 are largely driven by the pandemic. COVID-19 deaths contributed to nearly three-fourths or 74% of the decline from 2019 to 2020 and 50% of the decline from 2020 to 2021.

- An estimated 16% of the decline in life expectancy from 2020 to 2021 can be attributed to increases in deaths from accidents/unintentional injuries. Drug overdose deaths account for nearly half of all unintentional injury deaths.

- Other causes of death contributing to the decline in life expectancy from 2020 to 2021 include heart disease (4.1% of the decline), chronic liver disease and cirrhosis (3.0%), and suicide (2.1%).

Review report (CDC, 2022a): Provisional Life Expectancy Estimates for 2021

Deaths from cancer

Cancer was the second leading cause of death in the U.S. in 2020. In 2020, there were 602,350 cancer deaths; 284,619 were among females and 317,731 among males. In the past 20 years, from 2001 to 2020, cancer death rates decreased 27%, from 196.5 to 144.1 deaths per 100,000 population (CDC, 2022b).

Advancing age is the most important risk factor for cancer overall and for many individual cancer types, although cancer can be diagnosed at any age (National Cancer Institute, 2021). Lung cancer was the leading cause of cancer death, accounting for 23% of all cancer deaths. Other common causes of cancer death were cancers of the colon and rectum (9%), pancreas (8%), female breast (7%), prostate (5%), and liver and intrahepatic bile duct (5%). Other cancers individually accounted for less than 5% of cancer deaths. Bone cancer is most frequently diagnosed in children and adolescents (i.e., people under age 20), with about one-fourth of cases occurring in this age group (National Cancer Institute, 2021). Previous research suggests that trends in cancer death rates reflect population changes in cancer risk factors, screening test use, diagnostic practices, and treatment advances (CDC, 2022b).

Review report (CDC, 2022b): CDC – An Update on Cancer Deaths in the United States

Infant mortality

The infant mortality rate is the number of infant deaths for every 1,000 live births. In addition to giving us key information about maternal and infant health, the infant mortality rate is an important marker of the overall health of a society. In 2020, 19,578 infant deaths were reported in the U.S., a decline of 3% from 2019. The infant mortality rate was 5.42 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2020, a decline of 3% from the 2019 rate of 5.58 and the lowest rate reported in U.S. history (CDC, 2022c).

In 2020, the five leading causes of all infant deaths were the same as those in 2019: congenital malformations (21% of infant deaths), disorders related to short gestation and low birth weight (16%), sudden infant death syndrome (7%), unintentional injuries (6%), and maternal complications (6%). By state, infant mortality ranged from a low of 3.92 infant deaths per 1,000 births in California to a high of 8.12 in Mississippi. Geographically, infant mortality rates in 2020 were highest among states in the south (CDC, 2022c). The following report from the National Center for Health Statistics presents infant mortality statistics from 2020:

Review report (CDC, 2022c): Infant Mortality in the United States, 2020

1.3.2 Public Health

I. Key Terms:

- Clinical care: prevention, treatment, and management of illness and preservation of mental and physical well-being through services offered by medical and allied health professions, also known as healthcare.

- Determinant: a factor that contributes to the generation of a trait.

- Epidemic: an increase, often sudden, in the number of cases of a disease above what is normally expected in that population in that area.

- Health outcome: the result of a medical condition that directly affects the length or quality of a person’s life.

- Intervention: action or ministration (i.e., the act or process of ministering) that produces an effect or is intended to alter the course of a pathologic process.

- Pandemic: denoting a disease affecting or attacking the population of an extensive region, country, or continent.

- Population health: an approach to health that aims to improve the health of an entire population.

- Prevention: action to avoid, forestall, or circumvent a happening, conclusion, or phenomenon (e.g., disease).

(Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, n.d.)

II. Public Health Defined

There are clear distinctions between the practice of medicine and public health. The science, diagnostics, and treatment of diseases are at the center of the practice of medicine. Advances in medical science have created areas of practice specialization such as pediatrics, obstetrics, oncology, and geriatrics. Medical practitioners follow an ethos based on social responsibility, beneficence, gratitude, confidentiality, and humility to preserve human life and do no harm (Indla & Radhika, 2019). Dating back to 400 B.C., the Hippocratic Oath was the gold standard that physicians and medical auxiliaries followed; however, current practitioners must also consider bioethics. Medical practitioners treat individual patients and teach people how to take care of themselves. Whereas, public health professionals work to prevent the spread of communicable diseases, manage public health hazards, and respond to natural or man-made disasters.

III. Public Health Services

Control of communicable diseases is carried out by local and state health agencies in collaboration with the CDC (Salinsky, 2010). Local and state agencies conduct surveillance of communicable diseases and collect and analyze the data. Both private and state labs analyze specimens. Examples of communicable diseases of public health concern for becoming epidemics or pandemics are meningitis, West Nile Virus, Hanta Virus, influenza strains such as H1N1, the plague, and most recently the coronavirus. The CDC is notified of unusual or alarming outbreaks or trends. Control and prevention measures are then implemented by the CDC in collaboration with the affected area(s). Local public health departments offer both screening and treatment for endemic communicable diseases, such as STDs and tuberculosis (Salinsky, 2010).

Environmental hazards (i.e., non-infectious, non-occupational) are prevented, detected, and corrected by federal, state and local public health agencies or in some states by an environmental agency. At the federal level, the National Center for Environmental Health plans and directs an overall program of environmental harm reduction (CDC, 2019a). Also, the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry evaluates the risk of hazardous substances in the environment, identifies people at risk of exposure to hazardous substances, and prevents or minimizes the effects on health. The types of hazards typically controlled are air pollution, contaminated food and water, chemical spills, radon gas, mosquitoes, and other disease vectors (CDC, 2019b; Salinsky, 2010).

Efforts to prepare for emergencies, disasters, and terrorism are led by the CDC and the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response, which publish protocols for action for state and local government agencies (CDC, 2019a; Salinsky, 2010). However, each local public health agency is responsible for developing a customized plan based on CDC protocols. State governments play a key role by devoting resources to local preparedness planning (Salinsky, 2010). Preparedness and response efforts include surveillance, laboratory testing, outbreak investigation, and the treatment and quarantine of the population. In addition, plans must have a coordinated emergency medical response. In the event of an incident, state and local agencies are responsible for implementing the plan in collaboration with the CDC.

Federal and state governments fund health promotion and disease prevention services, while local health departments and community health centers provide the services. Most local public health departments provide screening and treatment for communicable diseases such as sexually transmitted diseases and tuberculosis. Many also provide services to high-risk women and children (i.e., low-income, special healthcare needs). Services may include perinatal home visits, well-child clinics, developmental screening, and nutrition counseling for women, infants, and children (WIC).

Some other prevention services include adult and childhood immunizations; screening for diabetes, cardiovascular, and other chronic diseases; smoking prevention and cessation; and prevention of HIV/AIDs, unintended pregnancy, obesity, inactivity, substance abuse, injuries, and violence. Supported educational activities include media campaigns, outreach to high-risk groups, and general population education. Some activities are conducted in partnership with non-governmental organizations, nonhealthcare-related local government agencies, or state health agencies. The amount of resources devoted to health promotion and disease prevention activities and the engagement of agencies vary by state and locality. Larger local health departments are more likely to provide a comprehensive set of services (Salinsky, 2010). Other public health services include the promotion of occupational health, surveillance of population health and well-being, screening programs, as well as mental, correctional, and child health services.