1.1 Historical Background

1.1.1 Medical Training

In the early years of the United States (U.S.) being a formal country, medical care largely lacked a firm foundation in scientific knowledge and principles. As a result, many treatments caused more harm than benefit to the patients (Rothstein, 1987). For example, physicians frequently used techniques now considered barbaric: bleeding, induced vomiting, and treatment with harmful agents such as mercury (Parascandola, 1976).

Before the mid 1800s, medical training was much less formal than the large academic institutions of today, with most physicians being trained as apprentices (Rothstein, 1972). By the mid-1850s, physicians started opening medical schools in affiliation with nearby universities, increasing the number of formal medical schools from only a small number to more than 40 by the mid-1850s (Rothstein, 1972). However, though the number of formal medical schools increased, the quality of education needed to be improved, and many medical schools needed more resources for medical education (Starr, 1982).

Through most of the nineteenth century, many different types of practitioners in the U.S. competed to provide care, much of which was of poor quality (Starr, 1982). In addition, physicians typically had neither particularly high incomes nor social status. This situation changed only gradually towards the beginning of the twentieth century with the confluence of various factors. These factors included a more scientific basis for medicine, improvements in medical training, improvements in the quality of hospitals, and consolidation of competing physician interests under the auspices of local (county) and state medical societies and nationally through the American Medical Association (AMA).

The 1910 publication of the Flexner Report represented a turning point in U.S. health policy. Commissioned by the Carnegie Foundation, the report provided a detailed account of the poor quality of most U.S. medical schools at the time. The report eventually led to improved medical school curricula, increased length of training, and stringent admission to training – as well as the closure of some of the worst medical school facilities. As a result, individuals faced higher barriers to entering the field.

Today, besides requiring a bachelor’s degree, physicians and surgeons typically need either a Medical Doctor (M.D.) or a Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine (D.O.) degree. No specific undergraduate degree is required to enter an M.D. or D.O. program. However, applicants to medical school usually have studied subjects such as biology, physical science, or healthcare and related fields. Some medical schools offer combined undergraduate and medical school programs that last six to eight years. Schools may also offer combined graduate degrees, such as dual Doctor of Medicine-Master of Business (M.D.-M.B.A.), dual Doctor of Medicine-Master of Public Health (M.D.-M.P.H.), or dual Doctor of Medicine-Doctor of Philosophy (M.D.-Ph.D.). After medical school, almost all graduates enter a residency program in their specialty of interest. A residency usually takes place in a hospital or clinic and varies in duration, typically lasting from three to nine years, depending on the specialty. Subspecialization, such as infectious diseases or hand surgery, includes additional training in one to three years of a fellowship. (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2022). According to the Association of American Medical Colleges (2021), as of 2020, there were 155 accredited MD-granting institutions and 41 accredited DO-granting institutions in the U.S.1.1.2

1.1.2 Hospitals

Hospitals in the early years were actually almshouses. Almshouses were simply housing facilities for chronically ill, older adults, those with severe mental illness, individuals with cognitive disabilities, and orphans (Rothstein, 1987). Later, pest houses were created to isolate healthy individuals from those infected with smallpox and other communicable diseases. Caring for the sick was a secondary goal of the pest houses, the primary goal being the isolation of healthy individuals (Rothstein, 1987). Due to the insufficient care provided by almshouses, physicians started calling for independent hospitals to be established in large cities. This call resulted in the establishment of Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia, Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, and New York Hospital in New York City. For example, Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia was founded in 1751 as the nation’s first institution to treat medical conditions. Unfortunately, though, these first hospitals fell short of their goals and merely supplemented the work of the almshouses rather than replacing them (Rothstein, 1987). During the early part of the nineteenth century, only poor, isolated, or socially disadvantaged individuals received medical care in hsopital institutions. When middle- or upper-class became sick or needed surgery, they were routinely taken care of in their own home (Rosenberg, 1987).

Hospitals changed dramatically during the latter part of the nineteenth century and the first part of the twentieth century. Previously their reputation was poor; they were places to be avoided by those who had alternatives (i.e., people who could afford it received care in their homes), and they mainly served the poor. However, as the scientific basis of medicine improved, facilities were enhanced and physicians became better trained – the hospital was transformed. The modern hospital evolved into a not-for-profit organization wherein physicians were granted clinical privileges to treat their patients.

Definition: Clinical privileges are permissions to provide medical and other patient care services in the granting institution, within defined limits, based on the individual’s education, professional license, experience, competence, ability, health, and judgment (Military Health System, 2013).

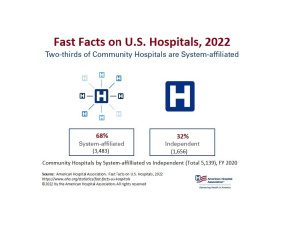

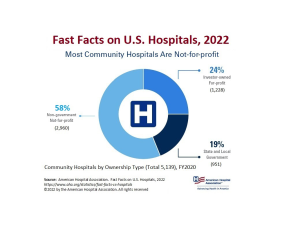

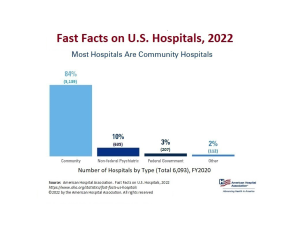

This model was particularly appealing to the medical community because physicians could avail themselves of the latest technology and a cadre of trained nurses free of charge – which has been dubbed a ‘rent-free workshop’ (Gabel & Redisch, 1979). The following infographics from the American Hospital Association (2022) includes statistics regarding the number of hospitals by type as of the year 2020:

Link to infographic: AHA – Fast Facts on U.S. Hospitals, 2022

1.1.3 Health Insurance

According to the U.S. Census Bureau (2021a), private health insurance is coverage by a health plan provided through an employer or union, purchased by an individual from a private health insurance company, or coverage through TRICARE. Public health insurance includes plans funded by governments at the federal, state, or local levels. The major categories of public health insurance are Medicare, Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), Veterans health care program, state-specific plans, and the Indian Health Service (IHS).

Private sector

The U.S. healthcare system developed largely through the private sector. The first health plan started in 1929 to serve teachers. This model served as the blueprint for the first Blue Cross plans available in the U.S. (Raffel, 1980). However, the concept of insurance coverage began as workers’ compensation, providing pay to workers who lost work due to job-related injuries or illness. By 1912, many countries in Europe had started national health insurance plans. The U.S. resisted this with its entry into World War I as national insurance was considered social insurance, strongly affiliated with German ideals (Starr, 1982).

Private health insurance in the U.S. began around the early 1930s, with the establishment of non-profit Blue Cross plans for hospital care and soon after that Blue Shield plans for physician care. The genesis of Blue Cross was a desire for hospital coverage on the part of workers and employers on the one hand, and on the other, the need for a steady stream of revenues on the part of hospitals mired in the Great Depression. The first hospital insurance plan began in 1929 in Dallas, Texas (Braveman & Metzler, 2012). In other parts of the country, hospitals banded together to provide this coverage under the auspices of Blue Cross, allowing enrollees to have the freedom to choose their hospital. These arrangements were non-profit and did not require the cash reserves typical of private insurance because hospitals guaranteed the provision of services, which was possible because of empty beds during the Depression (Starr, 1982). Near the end of the 1930s, Blue Shield plans that covered physicians’ services were established under similar principles: non-profit status and free choice of provider.

Blue Cross and Blue Shield plans began encountering competition from commercial (for-profit) insurers, particularly after the Second World War. While the Blues had, until that time, used ‘community rating’ (where all contracting groups pay the same price for insurance), commercial insurers employed ‘experience rating’ (where premiums vary based on the past health status of the insured group), allowing them to charge lower prices to employer groups with lower expected medical expenses. Eventually, the Blues had to follow suit and switch to experience rating to remain competitive, blurring the distinction between the non-profit and for-profit insurers (Law, 1974; Starr, 1982). As a result, by 1951 more Americans obtained hospital insurance from commercial insurers than Blue Cross (Law, 1974).

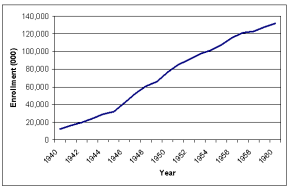

The number of Americans with private health insurance coverage grew dramatically from 1940 to 1960 (Figure 1-1). While only six million had some type of health insurance coverage in 1939, this had risen to 75 million people or half the population by 1950 which was only about 10 years (Health Insurance Institute, 1961). By the time Medicare and Medicaid were enacted in 1965, insurance coverage (public and private) had further expanded to 156 million – 80% of the population (Jost, 2007). The tremendous growth rate in private insurance during this period was partly because employer contributions to employee private health insurance plans were not considered taxable income for the employee (Gabel, 1999; Helms, 2008).

Figure 1-1

Number of Persons with Health Insurance (thousands), 1940-1960

(Health Insurance Institute, 1961)

However, there were other reasons for expanding private insurance through employment. Unions negotiated for coverage for their members, which was considered an important benefit because healthcare costs were rising at the time (Jost, 2007). There are also economies of scale involved in purchasing through a group, and premiums tend to be lower since there is less concern about adverse selection. These factors, coupled with rising incomes with the onset and conclusion of the Second World War and new organizational forms to provide coverage, also help explain the growth (Cunningham, 2000). With no systematic government program for providing coverage until the mid-1960s, this demand was partly satisfied through the employment-based system, at least for many of those in the workplace.

As a non-profit organization, the Blues gave communities access to medical care and protection against personal financial ruin by accepting all individuals regardless of health status. By the 1970s and ’80s, however, Blue plans were losing market share to for-profit insurance companies marketing to healthier populations and charging lower premiums. In 1994, the Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association’s Board of Directors voted to eliminate the membership standard that requires member Plans to be organized as not-for-profit companies. As a result, several Blue Cross and Blue Shield plans reorganized into for-profit organizations.

Public sector

No major government health insurance programs operated until the mid-1960s, and most government involvement until then was through state rather than federal regulations. Then, in 1965, the first major federal health insurance programs, Medicare and Medicaid, were established. Before their creation, various indigent and charity care programs existed for low-income patients. In one such program, begun in 1950, the federal government matched state payments to medical providers for those receiving public assistance. In another, the Kerr-Mills Act of 1960 provided assistance to states to help seniors who were not on public assistance but who required help with their medical bills (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [DHHS], 2000). Aside from the Affordable Care Act, the creation of Medicare and Medicaid is likely the most significant health policy to date.

Medicare covered Americans aged 65 and older, and Medicaid covered about half of those with low incomes. In 1972, Medicare coverage was expanded to include the disabled population and those with end-stage renal disease. Before the enactment of Medicare, it was common for elderly Americans to be without health insurance. For example, over half of Americans aged 65 and older had hospital coverage before 1963, with far fewer insured for surgery or outpatient care (DHHS, 2010a). Moreover, hospital coverage among seniors before 1963 varied by region, from a low of 43% to a high of 68% (Finkelstein, 2007). However, since Medicare was enacted, almost all Americans aged 65 and over are covered for hospital and physician care. At its inception, Medicare was divided into two parts. Part A: Hospital Insurance was social insurance in that it was funded by payroll taxes on the working population. Part B: Supplemental Medical Insurance covered outpatient and physician visits and, although voluntary, was purchased by nearly all seniors since 75% of the premiums were paid from general federal revenues. Medicaid, in contrast, reflected a welfare model in that only those who met both income and certain categorical eligibility requirements (e.g., children under the age of 18 and female adults with children) could receive the coverage, which was largely provided free of patient charges.

Passage of the Medicare legislation (i.e., Title XVIII of the Social Security Act) was difficult. Proposals to cover seniors had been before Congress for more than a decade but did not make headway in part due to opposition from organized medicine. As a result, passage of the legislation did not occur until several compromises were made, including payments to hospitals based on their costs, payments to physicians based on their charges, and the use of private insurers to administer the program. Eventually, the federal government moved to enact payment reforms to control Medicare costs. In 1983, Congress adopted the diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) system for Medicare, which changed hospital reimbursement from a retrospective system based on costs to a fixed prospective payment based on the patient’s diagnosis. Then in 1989, Congress enacted a Medicare fee schedule for physicians in the form of a Resource-Based Relative Value Scale (RBRVS) to replace the previous charge-based system, with further controls being put on annual rates of increase in aggregate program payments. The RBRVS system also aimed to reduce the gap in payments for the provision of primary care services compared to specialist services.

One notable gap in Medicare benefits was outpatient prescription drug coverage. In 1988 the Medicare Catastrophic Coverage Act was signed into law. The law added drug coverage and other provisions related to long-term care, but Congress repealed it just a year later. One reason was that the new benefit would be funded entirely by Medicare beneficiaries. Many of them, however, already had supplemental prescription drug coverage through a former employer. There was also tremendous confusion about what the law did and did not cover (Rice et al., 1990). Almost two decades later, in 2003, a drug benefit was successfully added to Medicare, effective January 2006. Beneficiaries obtain their drug coverage by purchasing it from private insurers, who compete for subscribers among Medicare beneficiaries. The benefit is subsidized in the order of 75% by general federal revenues.

In March 2010, the U.S. enacted major healthcare reform. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) expanded coverage to the majority of uninsured Americans through:

- Subsidies aimed at lower-income individuals and families to purchase coverage;

- A mandate that most Americans obtain insurance or face a penalty; (Note: Legislation passed in late 2017 ended federal penalties beginning with the 2019 tax year; however, individual states can still impose a penalty.)

- A requirement that firms with over 50 employees offer coverage or pay a penalty;

- A major expansion of Medicaid;

- Regulating health insurers by requiring that they provide and maintain coverage to all applicants and not charge more for those with a history of illness, as well as requiring community rating, guaranteed issue, non-discrimination for pre-existing conditions, and conforming to a specified benefits package.

Most of the major provisions went into effect in 2014.