5.3 Value-Based Contracting in Healthcare

Sections:

5.3.1 Background

At its most fundamental, health risk (either clinical or financial) is a combination of two factors: the amount of loss and the probability of occurrence. Loss occurs when an individual’s post-occurrence state is less favorable than the pre-occurrence state. Financial risk is a function of loss amount and probability of occurrence, or in actuarial terminology, the frequency and severity of the loss. In the United States (U.S.), health risk has historically been the responsibility of payers (i.e., insurers, government programs, and employers). Healthcare payers have traditionally managed risk by combining pricing, underwriting, reinsurance, and claims management.

With the enactment of the HMO Act of 1973, managed care was developed in the 1990s as a series of initiatives designed to better manage the health of covered individuals and reduce unnecessary medical claims costs. The original approaches included network management, which is the process of identifying and contracting with preferred providers who offer either lower fees or lower utilization of services and steering patients to them, through benefit design or by requiring referrals. It also included utilization management through pre-authorization or concurrent review of hospital admissions.

In a quest for savings, these models devolved into restricting services and denials of care. Because of consumer reaction to the perceived restrictions and denials that resulted from these interventions, managed care plans began to seek other solutions to contain rapidly increasing costs. Techniques favored for managing utilization include implementing programs that encourage members to take responsibility for their own health. Other techniques aim to educate physicians in the most cost-effective, evidence-based treatments, such as chronic disease management and case management.

The chronic disease management programs of the early 2000s were implemented by payers and aimed to identify high-risk or high-need patients, particularly those who were not compliant with their treatments or had gaps in care. Patient management was usually performed externally, often via telephone, by nurses employed at large disease management organizations. Although attempts were made to involve the patient’s providers, providers were not party to the payer contract. This model peaked with several Medicare Coordinated Care and Support demonstration programs between 2005 and 2008 (Nelson, 2012; Peikes et al., 2008).

Because of the growth and importance of chronic disease management programs, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) established a major demonstration project, the Medicare Coordinated Care Project, to evaluate 15 different care coordination models (Peikes et al., 2008, 2009). Although the demonstration program showed some improvement in the quality of care delivered to patients, the lack of demonstrated savings led to a decline in the type of vendor-based disease management programs popular up to that time. It also led to an interest in programs that involved contracting directly with providers to take the risk for patient outcomes.

By the end of the first decade of the 21st Century, two things began to become clear: first, these programs were not containing medical costs, and second that the solution to rising costs had to include providers (Peikes et al., 2008). As a result, CMS’s attention shifted to alternative payment models incorporating providers directly and focusing on a combination of cost, quality, and patient satisfaction (i.e., the Triple Aim). This shift was a reaction to the quality of care delivered within the U.S. Healthcare system. A study by McGlynn et al. (2003) found that adults in the U.S. receive the generally accepted standard of preventive, acute, and chronic care only about 55% of the time. In addition, quality of care “varied substantially according to the particular medical condition, ranging from 78.7% of recommended care to 10.5% of recommended care for alcohol dependence” (McGlynn et al., 2003).

Pay for quality was intended to increase the frequency of these measures by rewarding physicians for their achievement of evidence-based quality measures (such as screenings, tests for patient populations, or adherence to prescriptions). The theory was that closing gaps in care and identifying health issues earlier would lead to reduced utilization of more expensive healthcare services later. The achievement of reduced cost of care in exchange for incentive payments made this a value-based initiative. Following the failure of the disease management model to demonstrate financial success, Congress passed several laws promoting different value-based initiatives, in addition to initiatives introduced by the Center for Innovation at CMS. These initiatives (in chronological order) include:

- Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act (MIPPA) 2008;

- Affordable Care Act (ACA) 2010;

- Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI and its successors) 2011;

- Protecting Access to Medicare Act (PAMA) 2014;

- The Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) 2015;

- Medicare’s direct contracting model: Global and Professional Direct Contracting Model (GPDC) 2020;

- Accountable Care Organization Realizing Equity, Access, and Community Health Model (ACO REACH) 2023.

In addition, CMS has introduced a number of alternative payment models (APMs). In these models, providers agree to accept a portion of their reimbursement, often in the form of a share of savings, based on the achievement of certain goals, including improved quality, reduced utilization, and reduced cost. APMs include Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) as well as models aimed at specific conditions or provider organizations: Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI), Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement, Comprehensive Primary Care, Comprehensive End-stage Renal Disease model, Kidney Care Choices model, and the Oncology Care Model (OCM). CMS’s stated objective is to move the entire healthcare market toward paying providers based on the quality rather than the quantity of care they give patients (Peikes et al., 2009).

5.3.2 Types of Value-Based Contracts

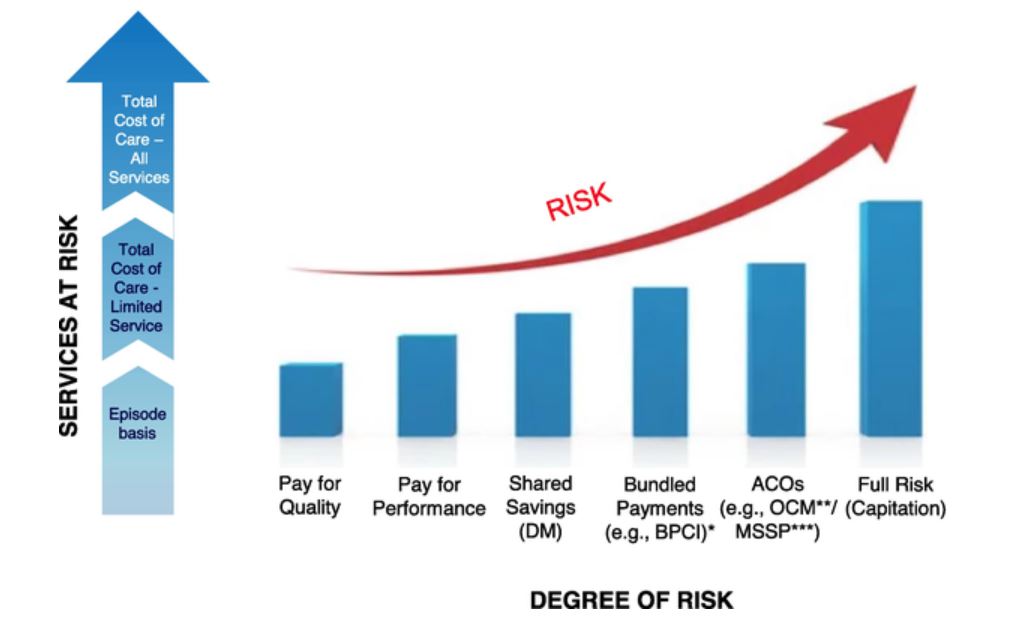

Werner et al. (2021) noted that, “the complexity of the current suite of alternative payment models” and the variety and lack of standardization of different models make value-based contracting challenging. Figure 5-1 illustrates the development and growth of alternative payment models. Over time, models have become more comprehensive, and the risk assumed by providers and healthcare management organizations (HCMs) has increased.

Figure 5-1

Risk and Value-Based Contract Types

(Duncan, 2022)

*BPCI: Bundled Payment for Care Improvement; **OCM: Oncology Care Model; ***MSSP: Medicare Shared Savings Program.

Figure 5-1 also illustrates the two dimensions of risk that are accepted by a provider or HCM: the x-axis indicates increasing degrees of financial risk, from none (i.e., supplemental pay for performance payments on top of regular provider reimbursement) to capitation (i.e., the potential for significant gain but also losses). The y-axis illustrates the extent of the services at risk incorporated in the contract. The extent of services at risk may range from a risk limited to a single episode of care only (e.g., knee surgery) to population risk in which the provider or HCM accepts financial risk for all expenses incurred by the target population.

I. Pay for Quality & Pay for Performance

According to Magill (2016), the original reimbursement model (i.e., fee-for-service) can be traced back “to to the origins of Blue Cross Blue Shield insurance in the 1930s.” In the fee-for-service (FFS) reimbursement model, each time the patient received a service from a physician, hospital, or pharmacist, a bill was generated and then paid by the patient or the payer (or both). As this system began to impose a financial strain on payers, different models evolved, beginning with payment for quality. Unfortunately, while these models improved quality metrics such as HEDIS – NCQA, they did not significantly reduce healthcare costs (McGlynn et al., 2003).

Closely aligned with pay for quality models is pay for performance, in which physicians are rewarded for patient metrics (such as mammograms for women, eye and foot exams for people with diabetes, etc.). The foundation of effective pay for performance initiatives is a collaboration with providers and other stakeholders to ensure that valid quality measures are used, that providers aren’t being pulled in conflicting directions, and that providers have support for achieving actual improvement.

II. Shared Savings

The big breakthrough in terms of financial risk transfer occurred with disease management programs in the early 2000s. Insurers that purchased disease management programs from vendors needed assurance that the programs would reduce medical costs. Lacking convincing randomized studies, vendors and payers contracted around a financial outcome; initially, vendors put a portion of their fees at risk of a favorable financial outcome. Later models allowed vendors to share in actual savings generated (i.e., gain-sharing) to the extent that the vendor reduced costs below a target (Duncan, 2014). There are different variations of gain-sharing models, with some being one-sided so only positive savings are shared. In contrast, others are two-sided so that if costs increase relative to the target, the vendor must reimburse some of the excess.

III. Bundled Payments

Traditionally, Medicare makes separate payments to providers for each of the individual services they furnish to beneficiaries for a single illness or course of treatment. This approach can result in fragmented care with minimal coordination across providers and health care settings. Payment rewards the quantity of services offered by providers rather than the quality of care furnished. “Research has shown that bundled payments can align incentives for providers – hospitals, post-acute care providers, physicians, and other practitioners – allowing them to work closely together across all specialties and settings” (CMS, 2022a).

“The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Innovation Center introduced the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) initiative in 2011 as one strategy to encourage healthcare organizations and clinicians to improve healthcare delivery for patients” (Hardin et al., 2017). This initiative tested four broadly defined models of care, which linked payments for the multiple services beneficiaries received during an episode of care (CMS, 2022a). Under the initiative, organizations entered into payment arrangements that included financial and performance accountability “for the full spectrum of delivery—both acute and postacute—as a single episode of care, defined as all related services up to 90 days after hospital discharge to treat a clinical condition or procedure” (Hardin et al., 2017).

The Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Advanced Model (BPCI Advanced) is a new iteration of this initiative. The BPCI Advanced Model launched with its first cohort of providers on October 1, 2018 and the period of performance ends on December 31, 2025 (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2020). The Avanced Model aims to support healthcare providers who invest in practice innovation and care redesign to better coordinate care and reduce expenditures, while improving the quality of care for Medicare beneficiaries. BPCI Advanced qualifies as an APM under the Quality Payment Program. The overarching goals of the BPCI Advanced Model are (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2023):

- Care Redesign

- Health Care Provider Engagement

- Patient and Caregiver Engagement

- Data Analysis/Feedback

- Financial Accountability.

An independent evaluation in 2020 (i.e., after two years) found (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2020):

Early evidence from the independent evaluation of the BPCI Advanced Model indicates that participating hospitals reduced Medicare FFS payments for most of the clinical episodes evaluated while maintaining quality of care. However, Medicare experienced net losses in the first ten months of the model after accounting for reconciliation payments. This underscores the challenges of identifying appropriate benchmarks in setting target prices within a prospective payment framework.

Review the BPCI findings at-a-glance (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2020): BPCI Advanced Year 2 Report – Findings at-a-Glance

IV. Accountable Care Organizations

The Affordable Care Act introduced Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs): provider groups that accept payment risk for their attributed populations in return for the opportunity to share savings when costs are reduced below an adjusted benchmark (United States Congress, 2010). In the original model, providers only accepted upside risk (shared savings only). In later models, providers could achieve a greater share of savings but at the cost of having to also share losses. ACO arrangements exist among all payers and payer types, including commercial insurers, traditional Medicare, and Medicaid. CMS’s Oncology Care Model is a similar initiative but limited to cancer patients undergoing treatment by oncologists.

V. Capitation

All these models involve some sharing of risk between the payer and providers. However, full risk transfer is achieved with capitated models. With capitation, the provider accepts full financial responsibility for all costs of a population or sub-population (e.g., primary care only). “Capitated managed care is the dominant way states deliver services to Medicaid enrollees. States pay Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) a set per member per month payment for the Medicaid services specified in their contracts” (Hinton & Musumeci, 2020).

5.3.3 What are Value-Based Programs?

There are five original value-based programs; their goal is to link provider performance of quality measures to provider payment (CMS, 2022b):

- End-Stage Renal Disease Quality Incentive Program (ESRD QIP): The CMS administers the ESRD QIP to promote high-quality services in renal dialysis facilities. The first of its kind in Medicare, this program changes how CMS pays for the treatment of patients who receive dialysis by linking a portion of payment directly to facilities’ performance on quality of care measures. These types of programs are known as “pay for performance” or “value-based purchasing” (VBP) programs.

- Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) Program: The Hospital VBP Program rewards acute care hospitals with incentive payments for the quality of care provided in the inpatient hospital setting. This program adjusts payments to hospitals under the Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS) based on the quality of care they deliver.

- Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (HRRP): HRRP is a Medicare value-based purchasing program that encourages hospitals to improve communication and care coordination to better engage patients and caregivers in discharge plans and, in turn, reduce avoidable readmissions.

- Value Modifier (VM) Program (also called the Physician Value-Based Modifier or PVBM): Mandated by the Affordable Care Act, this program seeks to financially reward physicians who provide healthcare that is high value-both high in quality, and low in cost.

- Hospital Acquired Conditions (HAC) Reduction Program: The HAC Reduction Program encourages hospitals to improve patients’ safety and reduce the number of conditions people experience during their time in a hospital, such as pressure sores and hip fractures after surgery.

There are also other value-based programs (CMS, 2022b):

- Skilled Nursing Facility Value-Based Purchasing (SNFVBP): The CMS awards incentive payments to skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) through the SNF VBP Program to encourage SNFs to improve the quality of care they provide to Medicare beneficiaries. The SNF VBP Program performance is currently based on a single measure of all-cause hospital readmissions.

- Home Health Value-Based Purchasing (HHVBP): The overall purpose of the HHVBP Model was to improve the quality and delivery of home healthcare services to Medicare beneficiaries with specific goals to 1) provide incentives for better quality care with greater efficiency, 2) study new potential quality and efficiency measures for appropriateness in the home health setting, and 3) enhance the public reporting process.

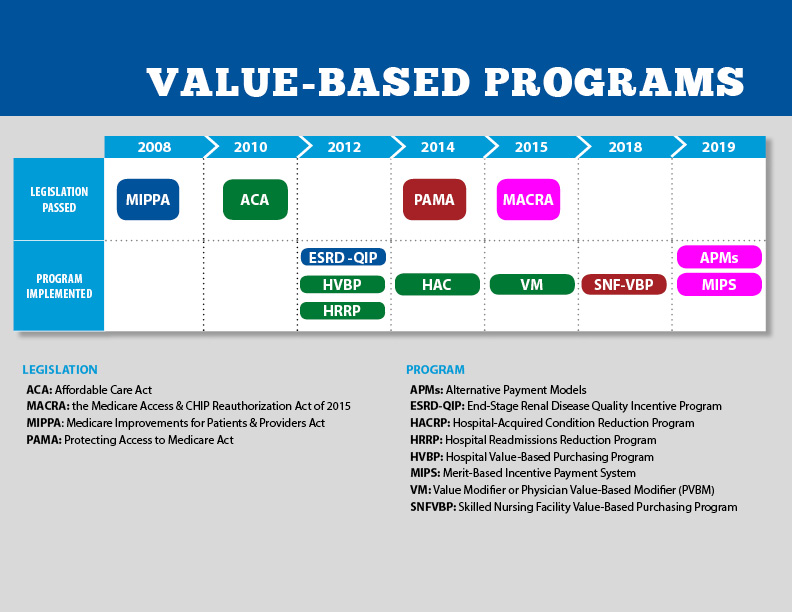

What’s the timeline for these programs (Fig. 5-2)?

Figure 5-2

CMS Value-Based Program Timeline

(CMS, 2022b)

Knowledge Check

Find the missing words in the word search below:

- At its most fundamental, health risk is a combination of two factors: amount of _____ and probability of _____.

- The original approaches to managed care included _____ management and _____ management.

- The _____ and lack of standardization of different _____ make value-based contracting challenging.

- With capitation the provider accepts full _____ responsibility for all costs of a _____.