4.4 Cost of Care

Sections:

4.4.1 Health Spending

The United States (U.S.) spends more per capita on healthcare than any other comparable high-income country and continues to spend more on healthcare at an unsustainable rate (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 2018; PWC Health Research Institute, 2022). In 2021, nearly 4.3 trillion dollars were spent by uninsured individuals, private health insurers, and federal and state governments on health consumption expenditures, accounting for approximately 18.3% of the nation’s gross domestic product (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS], 2022c; Wager et al., 2022). Moreover, following the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. spent nearly 10% more on healthcare, totaling more than 19% of its gross domestic product (Wager et al., 2022; CMS, 2022c). The gross domestic product (GDP) is the total monetary or market value of all the finished products and services produced within a country during a specified time frame. In other words, the GDP provides a scorecard of a country’s economic health.

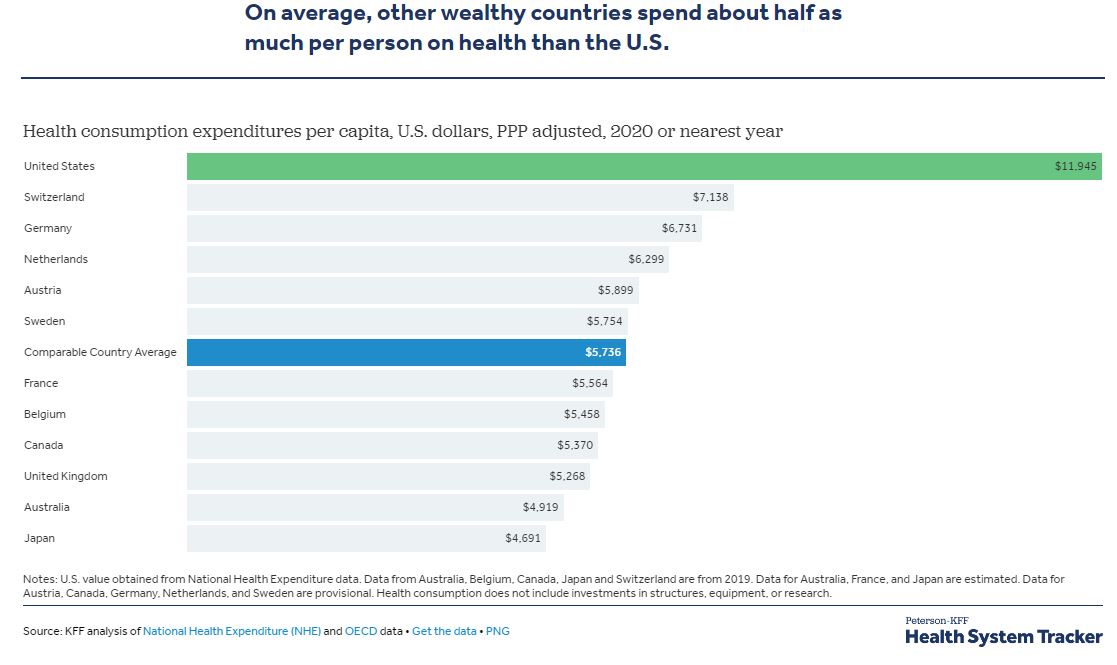

Healthcare spending is closely tied to a country’s wealth; however, comparing health expenditures across countries can be complicated due to unique health system structuring, the political landscape, and economic features that affect each country’s spending (Wager et al., 2022). The OECD consists of 38 countries with above-median national and per-person incomes that commit to democratic and market principles enabling comparisons to be drawn on the political and economic experiences between the high-income nations (Wager et al., 2022). As previously mentioned, the U.S. spends more on healthcare than all other countries in the OECD, while some countries, such as Turkey, spend as little as 4% of their GDP on healthcare. In 2020, the U.S. spent $11,945 on health expenditures per person, nearly twice as much as the average $5,736 the other high-income OECD countries spent on health per person (Fig. 4-5). Although health spending increased between 2019 and 2020 for all developed nations following the global pandemic, the U.S. was already spending the most per capita on health (Wager et al., 2022).

Figure 4-5

Health System Tracking

(Peterson-KFF Health Systems Tracker, 2023)

(Peterson-KFF Health Systems Tracker, 2023)

Definition: Medical tourism is when a patient intentionally crosses a border to seek medical care that will typically require out-of-pocket payment for services (De Arellano, 2007).

4.4.2 Cost Drivers

What determines the cost of healthcare? There are several national trends affecting the cost of healthcare. These include the aging population, increased costs of medical technology, increased prescription medication costs, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, and social determinants of health.

I. Aging Population

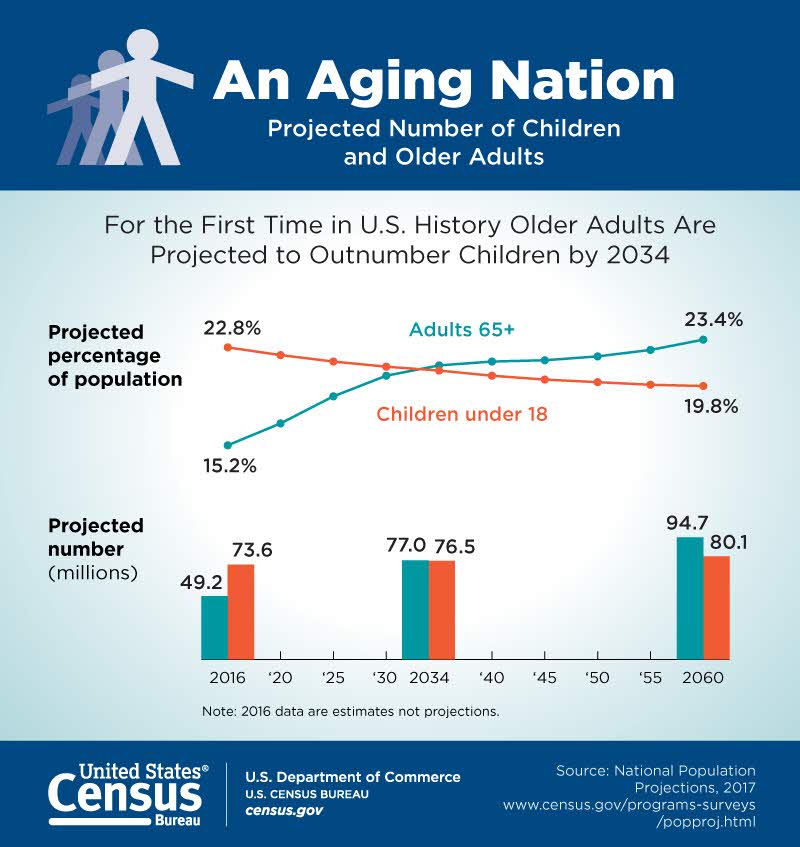

As demonstrated in Figure 4-6, the U.S. has a growing number of older adults (age 65 years or older) living longer than previous generations. As a result, older adults are anticipated to make up more than 20% of the U.S. population by 2030 (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ], n.d.). This demographic change will result in increased national healthcare costs because older adults typically experience more chronic conditions than younger populations, requiring expensive specialty and long-term care (AHRQ, n.d.).

Figure 4-6

A Growing Population of Older Adults

(U.S. Census Bureau, 2018)

II. Increased Costs of Medical Technology

Highly visible medical technologies, such as organ transplantation, diagnostic imaging systems, and biotechnology products, attract both praise and blame. Evolving medical technologies may save lives and improve a client’s health status, but they are also viewed as a dominant cause of the continued escalation of medical costs. Research suggests that medical technology accounts for about 10% to 40% of the increase in healthcare expenditures over time (Neumann & Weinstein, 1991). These costs also lead to further ethical dilemmas as decisions regarding what scarce resources are provided to which patients are made. Medical technologies, especially new ones, must justify their costs in a climate of competing claims on limited resources. Resource allocation follows American society’s objective of cost-effectiveness: if a new technology improves health outcomes at a lower cost than existing technologies, it should be adopted; otherwise, it should not (Neumann & Weinstein, 1991).

III. Increased Prescription Medication Costs

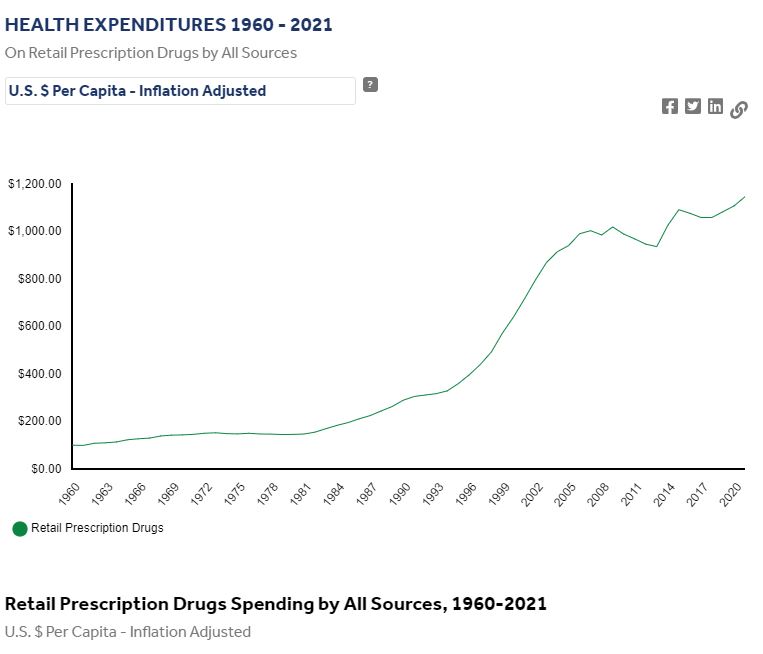

Retail prices for commonly-used prescription medications continue to increase twice as much as inflation, contributing to increased healthcare costs and making these life-sustaining medicines potentially unaffordable to many Americans. According to a recent AARP Rx Price Watch report, in 2020, prices for 260 commonly used medications increased by 2.9% while the general inflation rate was 1.3% (Bunis, 2021). For example, the cost of Symbicort, a medication used to treat asthma and COPD, increased 46%, from $2,940 to $4,282 (Bunis, 2021). See Figure 4-7 for an illustration related to spending on prescription drugs (Peterson-KFF Health Systems Tracker, 2023).

Although most Americans have either public or private insurance that helps them pay for medications, increased medication prices result in higher health insurance premiums and higher taxpayer costs for the Medicare and Medicaid programs. Some insurance companies only cover approved formulary medications (i.e., the list of generic and brand-name prescription medications covered by the insurance company). As a result, national organizations like the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) advocate for national policy changes, such as allowing Medicare to negotiate the prices of prescription medications with drug companies and allowing private insurance plans to have access to those lower prices (Bunis, 2021). Many consumers find themselves tasked with the difficult decision of purchasing expensive medication or going without prescribed medication and paying for their families’ housing and food.

Figure 4-7

Spending on Prescription Drugs

(Peterson-KFF Health Systems Tracker, 2023)

IV. Affordable Care Act

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, also known as the Affordable Care Act (ACA), was signed into law in 2010 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2022). This legislation aimed to increase consumers’ access to healthcare coverage and protect them from insurance practices that restricted care or significantly increased the cost of care. The ACA mandated health insurance coverage for employers and individuals. Employers were mandated to provide healthcare coverage based on the number of their employees. Individuals who were not covered through employer insurance plans were mandated to seek coverage through a newly created Marketplace. The Marketplace provides a central website that offers three standard health insurance coverage levels to facilitate comparison by consumers. As a result of the ACA and associated Medicaid expansion, 32 million people had healthcare coverage in 2021 (HealthCare.gov., n.d.; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, n.d.-d).

Key provisions of the ACA

The ACA includes the following key provisions (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2022):

- Insurers can no longer deny coverage or care for preexisting conditions like diabetes, asthma, and cancer.

- Young adults may remain on their parent’s insurance plans until they are 26 (even if they are married, financially independent, or not living with their parents).

- Health insurance plans cannot place annual or lifetime limits on coverage except for nonessential exceptions, such as cosmetic procedures.

- Many preventive services must be provided, such as:

- Well-child visits, flu shots, and other common vaccines

- Screening tests for blood pressure and diabetes

- Diagnostic screening tests, such as mammograms, and colonoscopies

- Counseling services related to mental health and substance use

The ACA also allows consumers to appeal to insurance companies for denials of care or payment of services, and restricts situations in which an insurance carrier may cancel a policy.

Challenges to the ACA

Although the ACA has significantly increased the number of Americans with health insurance coverage, it continues to be debated. Debates focus on increased taxes, increased insurance premiums, and some people’s belief that mandated coverage is a governmental intrusion on an individual’s rights. The ACA has been challenged three times without success. In 2012 the U. S. Supreme Court upheld mandated coverage as a constitutional exercise of Congress’s taxing powers because it could be interpreted as an individual’s choice to maintain health insurance or pay a tax. However, in 2017 Congress set the penalty for failing to comply with the mandate at zero dollars after multiple attempts to repeal and replace the ACA. In June 2021, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected a third major challenge regarding the constitutionality of the ACA. In a 7-to-2 decision, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the ACA based on the judgment that the states who brought forth the case did not prove damage to citizens because the fines for not having health coverage had been eliminated since the original legislation was passed (K&L Gates LLP, 2021).

V. Social Determinants of Health

Social determinants of health (SDOH) are the conditions in the environments where people live, learn, work, and play that affect a wide range of outcomes. SDOH directly impact individuals’ health behaviors, access to routine healthcare, and the development of chronic diseases. Yet, the U.S. spends a significantly lower percentage of its gross domestic product (GDP) on social services than similar countries with better health outcomes (Bush, 2018). Healthy People 2030, established by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, identifies public health priorities to help individuals, organizations, and communities across the U.S. improve health and well-being over the next decade by addressing SDOH. One of Healthy People 2030’s goals states, “Create social, physical, and economic environments that promote attaining the full potential for health and well-being for all” (Healthy People 2030, n.d.). SDOH includes healthcare access and quality, neighborhood and environment, social and community context, economic stability, and education access and quality (Fig. 4-8). These conditions have a major impact on people’s health and well-being, ultimately affecting national healthcare costs (Healthy People 2030, n.d.).

Figure 4-8

Five Key Areas of Social Determinants of Health

(Healthy People 2030, n.d.)