3.2 Private Health Insurance

3.2.1 Employer-Sponsored (Group) Insurance

Before 2010, the percentage of workers receiving employer-sponsored insurance ranged from 60%-69%, while post-2021, the range has held within the mid-50% range (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2021). The employer-sponsored insurance journey is similar to that of hospitals and physicians. Initially, medical insurance was what we categorize as catastrophic indemnity insurance, with copays ranging from 10%-20%. Catastrophic indemnity insurance pays only for significant expenses over a certain amount, such as hospitalization, similar to automobile insurance. Gradually more services were offered as part of medical insurance until any service, including preventive care, might be included in an employer-sponsored plan.

Initially, medical insurance was only for the employee and not the employee’s family. The growth in family coverage occurred following the 1949 Supreme Court ruling allowing benefits to become a part of labor negotiations and increasing the cost of medical insurance to employers. Medical (health) insurance cost escalation occurred in conjunction with the escalating cost of medical care to a point where executives found continued medical insurance price increases unsustainable. As a result, employers began to demand more for their money and their employees.

Executives pursued three lines of action to reduce escalating medical insurance costs. First, in the 1980s, they began shifting employer-sponsored insurance to managed care plans, which were developed to increase efficiency and cost controls of healthcare by combining financing, insurance, and service provision. Second, in the 1990s, employers demanded improved health outcomes, initiating the healthcare quality movement. Third, they began to require their employees to pay a portion of the premium and insisted upon other funding mechanisms such as copays and deductibles. After 1990, managed care plans became the dominant employer-sponsored insurance model. Limitations on patient choice in managed care led to a shift towards a hybrid approach. The most popular plan currently is the preferred provider organization (PPO) with elements of managed care and patient choice. Since 2010, high deductible PPO plans coupled with a health savings account, where employees are responsible for a large deductible before medical services are covered, are on a trajectory to become the most popular plan.

Review webpage (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2021): Employer Health Benefits Survey 2021

Several factors drive the demand for coverage, including the size of the employed population and subsidies available to employers to provide coverage. One of the main drivers is the cost of insurance. As healthcare costs rise, insurance becomes more costly to both the employer and the employee, depressing both offer and take-up rates. Moreover, coverage becomes less comprehensive through increases in patient cost-sharing requirements. Blavin et al. (2014) concluded that declines in employer-sponsored coverage are due almost entirely to the fact that per capita health spending rose more quickly than personal income.

Another driver is the changing nature of employment in the United States (U.S.). More specifically, there has been a gradual decline in manufacturing jobs and the increase in retail jobs. There has also been a transition from larger to smaller employers and from full-time to part-time jobs. One result was fewer union workers; traditionally, those in unions are more likely to have health insurance (Swartz, 2006).

3.2.2 Individual (Non-Group) Insurance

The individual health insurance markets are comprised of plans purchased directly from the insurer. Individual insurance plan rates are typically higher than the employer’s group rates. The individual insurance market has been around for about as long as the group market, accounting for about 4% to 6% of the total market. Individuals purchasing medical (health) insurance through the individual market include those employed by small employers (fewer than 50 employees) or professionals such as physicians or lawyers in solo or small practices. Individuals and families without an entry into the employer insurance market and those not eligible for Medicare and Medicaid seek coverage individually.

Prior to implementation of the major parts of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), individual coverage had several disadvantages over employer-group coverage and, therefore, would typically have been purchased only if the alternative was unavailable. It was rarely subsidized; administrative costs tended to be high (25–40%); health examinations were often necessary; cost-sharing requirements were, on average, higher; fewer types of services tended to be covered (e.g., maternity care may have been excluded); and frequently the insured person was put in an actuarial group characterized by poor or uncertain health (Whitmore et al., 2011). The ACA changed much of this: it provides significant subsidies, prohibits high administrative costs, has no health restrictions on enrollment, and requires that people of the same age be charged the same premiums regardless of health status. In addition, the ACA rearranged the individual market providing a federal government sliding scale subsidy for individuals between 100% to 400% of the federal poverty level. Plans purchased through the Marketplace are required to meet the ACA criteria of a quality plan.

Review webpage (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2019a): Changes in Enrollment in the Individual Health Insurance Market through Early 2019

3.2.3 Managed Care

I. The Triple Aim

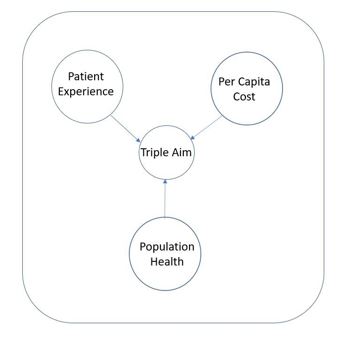

Despite nearly one out of five dollars in the U.S. being spent on healthcare, the U.S. consistently ranks among the worst out of industrialized countries for health outcomes, and it has only been exacerbated by COVID (Hartman et al., 2022). The ACA borrowed heavily from the concept of the Triple Aim (Fig. 3-1): simultaneously improving the patient experience of care, improving population health, and reducing the per capita costs of care (Institute for Healthcare Improvement, n.d.).

However, the U.S. stands out internationally for unusually high costs and poor outcomes among industrialized countries (Schneider et al., 2021). As a result, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) were authorized to specify quality measures that would best advance the National Quality strategic objective and build upon the Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting infrastructure. This framework also helped lead to the more formal establishment and proliferation of different types of managed care organizations (Aroh et al., 2015).

Figure 3-1

The Triple Aim

(Institute for Healthcare Improvement, n.d.)

II. Types of MCOs

Managed care organizations (MCOs) are integrated and coordinated organizations designed to provide care to a specific patient population. The main overreaching goals are to keep costs down while providing high-quality patient care (Heaton & Tadi, 2020). There are four main types of MCOs: Health Maintenance Organization (HMO), Preferred Provider Organization (PPO), Point of Service (POS), and Exclusive Provider Organization (EPO).

Health maintenance organizations ( HMOs)

Two features typically define health maintenance organizations: 1) the requirement of a designated gatekeeper and 2) the restriction to in-network providers under normal circumstances. A gatekeeper is a Primary Care Provider (PCP) responsible for preventative care screenings, routine physicals, and other primary care services. They are called a gatekeeper because the patient must first see the gatekeeper to obtain referrals to specialists. The idea is to keep the more expensive specialists reserved for conditions that cannot be handled by a primary care practitioner. The second restriction is that healthcare is only covered by the insurance plan if given by a hospital or provider who is in-network; otherwise, the patient is completely financially responsible. The only exception is typically for emergency room care, where a patient cannot be reasonably expected to verify in-network status. As a result, HMOs are generally the cheapest MCO (Falkson & Srinivasan, 2022). There are four common models of HMO organizations: group, independent practice association (IPA), network, and staff.

- Group Model - In the group model, the HMO contracts with a single, multispecialty entity for providers to provide care to its members. The HMO likely contracts additionally with a hospital in order to be able to provide comprehensive care to its members. The HMO pays the medical group a negotiated per capita rate, which the group distributes among its physicians, usually on a salaried basis.

- Independent Practice Association (IPA) Model - This set-up is closest to the original pre-paid plans mentioned above. An IPA is a group of independent practitioners and group providers who decide to form a legal contract with a separate legal entity known as the IPA. This IPA then contracts with the HMO to negotiate the administrative and logistical details of any arrangement, as well as some of the financial risk. That is part of why this model is so appealing to providers (Gold, 1999).

- Network Model - In this model, the HMO contracts with multiple provider groups, either single or multispecialty, to provide services to its members.

- Staff Model - This model involves the HMO directly employing providers on a salary basis. Typically, the HMO employs physicians in a range of specialties in order to more fully serve its patients in its own facilities. HMOs often find this appealing because they exert a great deal of control directly over the physicians. This model is also known as a closed-panel HMO.

On the patient side, there are premiums which are fees that must be paid on an annual or monthly basis. The premium enrolls the patient in the plan. When incurring medical costs, the first portion of the medical bill goes towards the deductible, which is the first portion of the medical bills sustained, which the patient must pay out-of-pocket before the insurance will pay for anything. The next fee possibly encountered is the copay. The copay is a flat fee (e.g., $35 for every primary care visit) paid out of pocket by the patient for a set service. The final out-of-pocket expenditure is coinsurance. Coinsurance is a percentage of the remaining balance that the patient must pay (e.g., the HMO will pay 80% of the procedure, and the patient must pay the remaining 20%).

The HMO pays providers typically through salary or capitation. Capitation is when a fixed sum of money is paid per time unit (usually monthly) per patient being treated by the provider. For example, a physician in the HMO with 100 patients designating her as their Primary Care Provider would receive a fixed sum for each of those 100 patients each month.

Preferred provider organizations (PPOs)

Preferred provider organizations provide patients with quite a bit more choice. There is no gatekeeper in a PPO. The next differential is that there are different coverage tiers, with patients allowed to go in-network and out-of-network to providers and still receive insurance coverage. However, by going out-of-network, they would incur larger costs, such as higher deductibles or higher coinsurance rates. These features make PPOs open-panel plans. In an open panel plan, the MCO provides incentives for the patients to use participating (i.e., in-network) providers but also allows patients to use out-of-network providers.

Local PPOs have a small service area and are open to beneficiaries who live in specified counties, much like most HMOs. Regional PPOs are much larger and contract with an entire region. Regional PPOs are required to serve areas defined by one or more states with a uniform benefits package across the service area. Regional PPOs have gained limited traction nationally because employers prefer local PPOs, although they are somewhat popular in the smaller states (Jacobson et al., 2017). Instead of paying providers with a capitation fee schedule, PPOs typically negotiate fee discounts with providers. Within the same hospital, the same procedure may be up to 31% cheaper than the average cost depending on the insurer (Craig et al., 2021).

Point of service (POS)

In the evolution of MCOs, point of service organizations are essentially trying to combine the costs saving aspects of the HMOs with the increased flexibility of choice of provider in a PPO. Under this structure, the patient has a gatekeeper, usually a primary care provider, who is an initial point of service for the patient. The patient is also responsible for getting referrals to specialists from this gatekeeper.

Exclusive provider organizations (EPO)

Exclusive provider organizations are somewhat like HMOs in that they only pay for in-network costs, and all out-of-network costs are the patient's responsibility. However, unlike HMOs, they do not require a gatekeeper, and patients are not required to get referrals to see other in-network providers (Table 2).

Table 2 A Comparison of Traditional MCOs

| Type of MCO | HMO | PPO | POS | EPO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gatekeeper | X | X | ||

| Out-of-Pocket Costs are Patient's Responsibility | X | X |

(HealthCare.gov., n.d-a)

III. Utilization Review

Utilization review (UR) is one of the primary tools utilized by MCOs to control over-utilization, reduce costs, and manage care. It can also be done to keep costs down or to ensure that proper protocols are being used in a fair and equitable way (Bohan et al., 2019). Utilization review can be required by hospitals, Worker’s Compensation, and insurance companies (Appelbaum & Parks, 2020; Bean et al., 2020; Siyarsarai et al., 2020). In addition to ensuring quality care, UR can be used to prevent fraud, waste, and inappropriate care from being provided to patients (Bean et al., 2020). There are three main types of utilization reviews:

- Prospective Utilization Review

- Concurrent Utilization Review

- Retrospective Utilization Review

When looking at these three types, the biggest difference in how they are conducted is when the review is done. Prospective UR, such as with prior authorization, is done prior to the medical services or procedures being delivered (Giardino & Wadhwa, 2022). Concurrent UR is conducted while the medical services are ongoing. Concurrent UR is often required by providers and can be used to validate the consumption of resources during a hospital stay, such as for inpatient case management where continuous review is necessary (Namburi & Tadi, 2022; Olakunle et al., 2011). It is also frequently associated with discharge planning to help ensure continuity of care (Smith et al., 2020). Finally, retrospective UR is done after the services are provided and the bill is delivered (Giardino & Wadhwa, 2022).

While there are some differences between these three methods, because of when they are conducted, there are many similarities between the basic procedures of these three approaches. The first step is to check eligibility with the insurance plan and/or ensure that the requested service is appropriate. If checking for appropriateness, typically, the insurer or plan will use nationally developed clinical guidelines for standards of care (Giardino & Wadhwa, 2022). The next step is to gather clinical information to determine if the criteria are met for the service. It is very important that the clinical staff document everything, including the absence of things, for this step to succeed. It may be common for clinical staff to fail to note things that look normal (i.e., “charting by exception”), but this can result in denials and delays during the UR process and is strongly discouraged. The provider will be notified If the reviewer determines that the criteria are met. If not, the provider and the patient will be notified of the denial, and they can appeal, usually by providing more information.