Appendix B Team Stepps Strategies

TeamSTEPPS®

TeamSTEPPS® is an evidence-based framework used to optimize team performance across the health care system. It is a mnemonic standing for Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and the Department of Defense (DoD) developed the TeamSTEPPS® framework as a national initiative to improve patient safety by improving teamwork skills and communication.[1]

Learn More

View this video about the TeamSTEPPS® framework[2]:

TeamSTEPPS® is based on establishing team structure and four teamwork skills: communication, leadership, situation monitoring, and mutual support. The components of this model are described in the following sections.

Team Structure

A nursing leader establishes team structure by assigning or identifying team members’ roles and responsibilities, holding team members accountable, and including clients and families as part of the team.

Communication

Communication is the first skill of the TeamSTEPPS® framework. As previously discussed, it is defined as a “structured process by which information is clearly and accurately exchanged among team members.” All team members should use these skills to ensure accurate interprofessional communication:

- Provide brief, clear, specific, and timely information to other team members.

- Seek information from all available sources.

- Use ISBARR and handoff techniques to communicate effectively with team members.

- Use closed-loop communication to verify information is communicated, understood, and completed.

- Document appropriately to facilitate continuity of care across interprofessional team members.

Leadership

Leadership is the second skill of the TeamSTEPPS® framework. As previously discussed, it is defined as the “ability to maximize the activities of team members by ensuring that team actions are understood, changes in information are shared, and team members have the necessary resources.” An example of a nursing team leader in an inpatient setting is the charge nurse.

Effective team leaders demonstrate the following responsibilities[3]:

- Organize the team.

- Identify and articulate clear goals (i.e., share the plan).

- Assign tasks and responsibilities.

- Monitor and modify the plan and communicate changes.

- Review the team’s performance and provide feedback when needed.

- Manage and allocate resources.

- Facilitate information sharing.

- Encourage team members to assist one another.

- Facilitate conflict resolution in a learning environment.

- Model effective teamwork.

Three major leadership tasks include sharing a plan, monitoring and modifying the plan according to situations that occur, and reviewing team performance. Tools to perform these tasks are discussed in the following subsections.

Sharing the Plan

Nursing team leaders identify and articulate clear goals to the team at the start of the shift during inpatient care using a “brief.” The brief is a short session to share a plan, discuss team formation, assign roles and responsibilities, establish expectations and climate, and anticipate outcomes and contingencies. See a Brief Checklist in the following box with questions based on TeamSTEPPS®.[4]

Brief Checklist

During the brief, the team should address the following questions:[5]

- Who is on the team?

- Do all members understand and agree upon goals?

- Are roles and responsibilities understood?

- What is our plan of care?

- What are staff and provider’s availability throughout the shift?

- How is workload shared among team members?

- Who are the sickest clients on the unit?

- Which clients have a high fall risk or require 1:1?

- Do any clients have behavioral issues requiring consistent approaches by the team?

- What resources are available?

Monitoring and Modifying the Plan

Throughout the shift, it is often necessary for the nurse leader to modify the initial plan as patient situations change on the unit. A huddle is a brief meeting before and/or during a shift to establish situational awareness, reinforce plans already in place, and adjust the teamwork plan as needed. Read more about situational awareness in the “Situation Monitoring” subsection below.

Reviewing the Team’s Performance

When a significant or emergent event occurs during a shift, such as a “code,” it is important to later review the team’s performance and reflect on lessons learned by holding a “debrief” session. A debrief is an informal information exchange session designed to improve team performance and effectiveness through reinforcement of positive behaviors and reflection on lessons learned.[6] See the following box for a Debrief Checklist.

Debrief Checklist[7]

The team should address the following questions during a debrief:

- Was communication clear?

- Were roles and responsibilities understood?

- Was situation awareness maintained?

- Was workload distribution equitable?

- Was task assistance requested or offered?

- Were errors made or avoided?

- Were resources available?

- What went well?

- What should be improved?

Situation Monitoring

Situation monitoring is the third skill of the TeamSTEPPS® framework and is defined as the “process of actively scanning and assessing situational elements to gain information or understanding, or to maintain awareness to support team functioning.” Situation monitoring refers to the process of continually scanning and assessing the situation to gain and maintain an understanding of what is going on around you. Situation awareness refers to a team member knowing what is going on around them. The team leader creates a shared mental model to ensure all team members have situation awareness and know what is going on as situations evolve. The STEP tool is used by team leaders to assist with situation monitoring.[8]

STEP

The STEP tool is a situation monitoring tool used to know what is going on with you, your patients, your team, and your environment. STEP stands for Status of the patients, Team members, Environment, and Progress toward goal. See an illustration of STEP in Figure 7.7.[9] The components of the STEP tool are described in the following box.[10]

- AHRQ. (2019, June). TeamSTEPPS 2.0. https://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps/instructor/index.html ↵

- AHRQ Patient Safety. (2015, April 29). TeamSTEPPS overview. [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/p4n9xPRtSuU ↵

- AHRQ. (2020, January). Pocket guide: TeamSTEPPS. https://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps/instructor/essentials/pocketguide.html ↵

- AHRQ. (2020, January). Pocket guide: TeamSTEPPS. https://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps/instructor/essentials/pocketguide.html ↵

- AHRQ. (2020, January). Pocket guide: TeamSTEPPS. https://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps/instructor/essentials/pocketguide.html ↵

- AHRQ. (2020, January). Pocket guide: TeamSTEPPS. https://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps/instructor/essentials/pocketguide.html ↵

- AHRQ. (2020, January). Pocket guide: TeamSTEPPS. https://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps/instructor/essentials/pocketguide.html ↵

- AHRQ. (2020, January). Pocket guide: TeamSTEPPS. https://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps/instructor/essentials/pocketguide.html ↵

- “stepfig1.jpg” by unknown author is licensed under Public Domain. Access for free at https://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps/instructor/essentials/pocketguide.html ↵

- AHRQ. (2020, January). Pocket guide: TeamSTEPPS. https://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps/instructor/essentials/pocketguide.html ↵

The third IPEC competency focuses on interprofessional communication and states, “Communicate with patients, families, communities, and professionals in health and other fields in a responsive and responsible manner that supports a team approach to the promotion and maintenance of health and the prevention and treatment of disease.”[1] See Figure 5.1[2] for an image of interprofessional communication supporting a team approach. This competency also aligns with The Joint Commission’s National Patient Safety Goal for improving staff communication.[3] See the following box for the components associated with the Interprofessional Communication competency.

Components of IPEC’s Interprofessional Communication Competency[4]

- Choose effective communication tools and techniques, including information systems and communication technologies, to facilitate discussions and interactions that enhance team function.

- Communicate information with patients, families, community members, and health team members in a form that is understandable, avoiding discipline-specific terminology when possible.

- Express one’s knowledge and opinions to team members involved in patient care and population health improvement with confidence, clarity, and respect, working to ensure common understanding of information, treatment, care decisions, and population health programs and policies.

- Listen actively and encourage ideas and opinions of other team members.

- Give timely, sensitive, constructive feedback to others about their performance on the team, responding respectfully as a team member to feedback from others.

- Use respectful language appropriate for a given difficult situation, crucial conversation, or conflict.

- Recognize how one’s uniqueness (experience level, expertise, culture, power, and hierarchy within the health care team) contributes to effective communication, conflict resolution, and positive interprofessional working relationships.

- Communicate the importance of teamwork in patient-centered care and population health programs and policies.

Transmission of information among members of the health care team and facilities is ongoing and critical to quality care. However, information that is delayed, inefficient, or inadequate creates barriers for providing quality of care. Communication barriers continue to exist in health care environments due to interprofessional team members’ lack of experience when interacting with other disciplines. For instance, many novice nurses enter the workforce without experiencing communication with other members of the health care team (e.g., providers, pharmacists, respiratory therapists, social workers, surgical staff, dieticians, physical therapists, etc.). Additionally, health care professionals tend to develop a professional identity based on their educational program with a distinction made between groups. This distinction can cause tension between professional groups due to diverse training and perspectives on providing quality patient care. In addition, a health care organization’s environment may not be conducive to effectively sharing information with multiple staff members across multiple units.

In addition to potential educational, psychological, and organizational barriers to sharing information, there can also be general barriers that impact interprofessional communication and collaboration. See the following box for a list of these general barriers.[5]

General Barriers to Interprofessional Communication and Collaboration[6]

- Personal values and expectations

- Personality differences

- Organizational hierarchy

- Lack of cultural humility

- Generational differences

- Historical interprofessional and intraprofessional rivalries

- Differences in language and medical jargon

- Differences in schedules and professional routines

- Varying levels of preparation, qualifications, and status

- Differences in requirements, regulations, and norms of professional education

- Fears of diluted professional identity

- Differences in accountability and reimbursement models

- Diverse clinical responsibilities

- Increased complexity of patient care

- Emphasis on rapid decision-making

There are several national initiatives that have been developed to overcome barriers to communication among interprofessional team members. These initiatives are summarized in Table 5.5a.[7]

Table 5.5a Initiatives to Overcome Barriers to Interprofessional Communication and Collaboration[8]

| Action | Description |

|---|---|

| Teach structured interprofessional communication strategies | Structured communication strategies, such as ISBARR, handoff reports, I-PASS reports, and closed-loop communication should be taught to all health professionals. |

| Train interprofessional teams together | Teams that work together should train together. |

| Train teams using simulation | Simulation creates a safe environment to practice communication strategies and increase interdisciplinary understanding. |

| Define cohesive interprofessional teams | Interprofessional health care teams should be defined within organizations as a cohesive whole with common goals and not just a collection of disciplines. |

| Create democratic teams | All members of the health care team should feel valued. Creating democratic teams (instead of establishing hierarchies) encourages open team communication. |

| Support teamwork with protocols and procedures | Protocols and procedures encouraging information sharing across the whole team include checklists, briefings, huddles, and debriefing. Technology and informatics should also be used to promote information sharing among team members. |

| Develop an organizational culture supporting health care teams | Agency leaders must establish a safety culture and emphasize the importance of effective interprofessional collaboration for achieving good patient outcomes. |

Communication Strategies

Several communication strategies have been implemented nationally to ensure information is exchanged among health care team members in a structured, concise, and accurate manner to promote safe patient care. Examples of these initiatives are ISBARR, handoff reports, closed-loop communication, and I-PASS. Documentation that promotes sharing information interprofessionally to promote continuity of care is also essential. These strategies are discussed in the following subsections.

ISBARR

A common format used by health care team members to exchange client information is ISBARR, a mnemonic for the components of Introduction, Situation, Background, Assessment, Request/Recommendations, and Repeat back.[9],[10]

- Introduction: Introduce your name, role, and the agency from which you are calling.

- Situation: Provide the client’s name and location, the reason you are calling, recent vital signs, and the status of the client.

- Background: Provide pertinent background information about the client such as admitting medical diagnoses, code status, recent relevant lab or diagnostic results, and allergies.

- Assessment: Share abnormal assessment findings and your evaluation of the current client situation.

- Request/Recommendations: State what you would like the provider to do, such as reassess the client, order a lab/diagnostic test, prescribe/change medication, etc.

- Repeat back: If you are receiving new orders from a provider, repeat them to confirm accuracy. Be sure to document communication with the provider in the client’s chart.

Nursing Considerations

Before using ISBARR to call a provider regarding a changing client condition or concern, it is important for nurses to prepare and gather appropriate information. See the following box for considerations when calling the provider.

Communication Guidelines for Nurses[11]

- Have I assessed this client before I call?

- Have I reviewed the current orders?

- Are there related standing orders or protocols?

- Have I read the most recent provider and nursing progress notes?

- Have I discussed concerns with my charge nurse, if necessary?

- When ready to call, have the following information on hand:

- Admitting diagnosis and date of admission

- Code status

- Allergies

- Most recent vital signs

- Most recent lab results

- Current meds and IV fluids

- If receiving oxygen therapy, current device and L/min

- Before calling, reflect on what you expect to happen as a result of this call and if you have any recommendations or specific requests.

- Repeat back any new orders to confirm them.

- Immediately after the call, document with whom you spoke, the exact time of the call, and a summary of the information shared and received.

Read an example of an ISBARR report in the following box.

Sample ISBARR Report From a Nurse to a Health Care Provider

I: “Hello Dr. Smith, this is Jane Smith, RN from the Med-Surg unit.”

S: “I am calling to tell you about Ms. White in Room 210, who is experiencing an increase in pain, as well as redness at her incision site. Her recent vital signs were BP 160/95, heart rate 90, respiratory rate 22, O2 sat 96% on room air, and temperature 38 degrees Celsius. She is stable but her pain is worsening.”

B: “Ms. White is a 65-year-old female, admitted yesterday post hip surgical replacement. She has been rating her pain at 3 or 4 out of 10 since surgery with her scheduled medication, but now she is rating the pain as a 7, with no relief from her scheduled medication of Vicodin 5/325 mg administered an hour ago. She is scheduled for physical therapy later this morning and is stating she won’t be able to participate because of the pain this morning.”

A: “I just assessed the surgical site and her dressing was clean, dry, and intact, but there is 4 cm redness surrounding the incision, and it is warm and tender to the touch. There is moderate serosanguinous drainage. Her lungs are clear and her heart rate is regular. She has no allergies. I think she has developed a wound infection.”

R: “I am calling to request an order for a CBC and increased dose of pain medication.”

R: “I am repeating back the order to confirm that you are ordering a STAT CBC and an increase of her Vicodin to 10/325 mg.”

Handoff Reports

Handoff reports are defined by The Joint Commission as “a transfer and acceptance of patient care responsibility achieved through effective communication. It is a real-time process of passing patient specific information from one caregiver to another, or from one team of caregivers to another, for the purpose of ensuring the continuity and safety of the patient’s care.”[12] In 2017 The Joint Commission issued a sentinel alert about inadequate handoff communication that has resulted in patient harm such as wrong-site surgeries, delays in treatment, falls, and medication errors.[13]

The Joint Commission encourages the standardization of critical content to be communicated by interprofessional team members during a handoff report both verbally (preferably face to face) and in written form. Critical content to communicate to the receiver in a handoff report includes the following components[14]:

- Sender contact information

- Illness assessment, including severity

- Patient summary, including events leading up to illness or admission, hospital course, ongoing assessment, and plan of care

- To-do action list

- Contingency plans

- Allergy list

- Code status

- Medication list

- Recent laboratory tests

- Recent vital signs

Several strategies for improving handoff communication have been implemented nationally, such as the Bedside Handoff Report Checklist, closed-loop communication, and I-PASS.

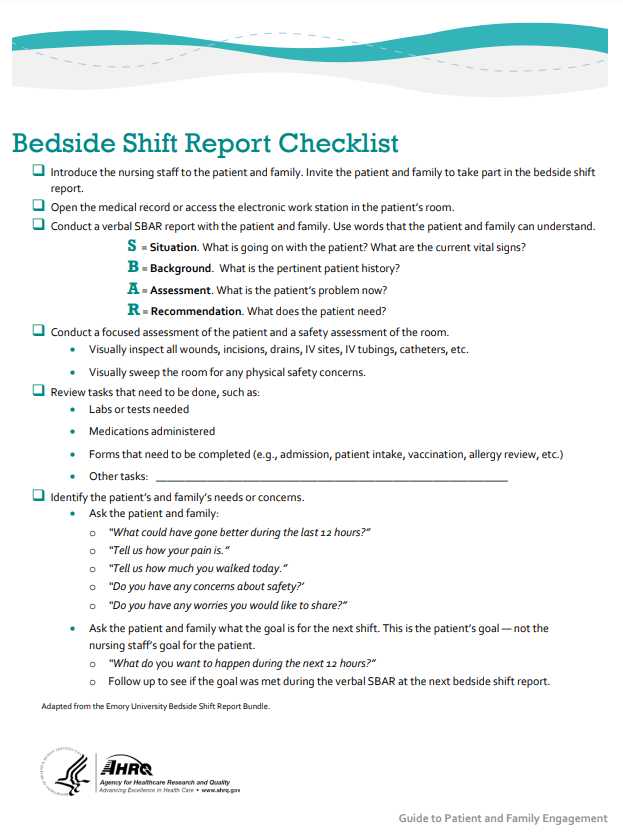

Bedside Handoff Report Checklist

See Figure 5.2[15] for an example of a Bedside Handoff Report Checklist to improve nursing handoff reports by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).[16] Although a bedside handoff report is similar to an ISBARR report, it contains additional information to ensure continuity of care across nursing shifts.

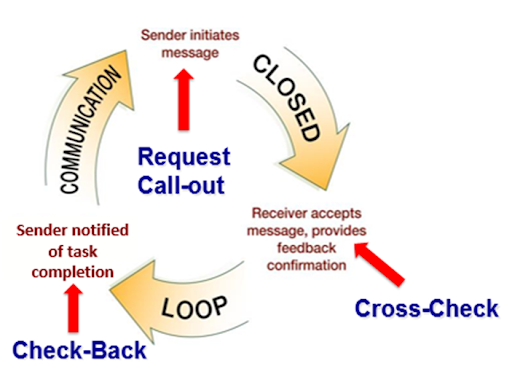

Closed-Loop Communication

The closed-loop communication strategy is used to ensure that information conveyed by the sender is heard by the receiver and completed. Closed-loop communication is especially important during emergency situations when verbal orders are being provided as treatments are immediately implemented. See Figure 7.3[17] for an illustration of closed-loop communication.

- The sender initiates the message.

- The receiver accepts the message and repeats back the message to confirm it (i.e., “Cross-Check”).

- The sender confirms the message.

- The receiver notified the sender the task was completed (i.e., “Check-Back”).

See an example of closed-loop communication during an emergent situation in the following box.

Closed-Loop Communication Example

Doctor: "Administer 25 mg Benadryl IV push STAT."

Nurse: "Give 25 mg Benadryl IV push STAT?"

Doctor: "That's correct."

Nurse: "Benadryl 25 mg IV push given at 1125."

I-PASS

I-PASS is a mnemonic used to provide structured communication among interprofessional team members. I-PASS stands for the following components[18]:

I: Illness severity

P: Patient summary

A: Action list

S: Situation awareness and contingency plans

S: Synthesis by receiver (i.e., closed-loop communication)

See a sample I-PASS Handoff in Table 7.5b.[19]

Table 5.5b Sample I-PASS Verbal Handoff[20]

| I | Illness Severity | This is our sickest patient on the unit, and he's a full code. |

|---|---|---|

| P | Patient Summary | AJ is a 4-year-old boy admitted with hypoxia and respiratory distress secondary to left lower lobe pneumonia. He presented with cough and high fevers for two days before admission, and on the day of admission to the emergency department, he had worsening respiratory distress. In the emergency department, he was found to have a sodium level of 130 mg/dL likely due to volume depletion. He received a fluid bolus, and oxygen administration was started at 2.5 L/min per nasal cannula. He is on ceftriaxone. |

| A | Action List | Assess him at midnight to ensure his vital signs are stable. Check to determine if his blood culture is positive tonight. |

| S | Situations Awareness & Contingency Planning | If his respiratory distress worsens, get another chest radiograph to determine if he is developing an effusion. |

| S | Synthesis by Receiver | Ok, so AJ is a 4-year-old admitted with hypoxia and respiratory distress secondary to a left lower lobe pneumonia receiving ceftriaxone, oxygen, and fluids. I will assess him at midnight to ensure he is stable and check on his blood culture. If his respiratory status worsens, I will repeat a radiograph to look for an effusion. |

Documentation

Accurate, timely, concise, and thorough documentation by interprofessional team members ensures continuity of care for their clients. It is well-known by health care team members that in a court of law the rule of thumb is, “If it wasn’t documented, it wasn’t done.” Any type of documentation in the electronic health record (EHR) is considered a legal document. Abbreviations should be avoided in legal documentation and some abbreviations are prohibited. Please see a list of error prone abbreviations in the box below.

Read the current list of error-prone abbreviations by the Institute of Safe Medication Practices. These abbreviations should never be used when communicating medical information verbally, electronically, and/or in handwritten applications. Abbreviations included on The Joint Commission’s “Do Not Use” list are identified with a double asterisk (**) and must be included on an organization’s “Do Not Use” list.

Nursing staff access the electronic health record (EHR) to help ensure accuracy in medication administration and document the medication administration to help ensure patient safety. Please see Figure 5.4[21] for an image of a nurse accessing a client’s EHR.

The electronic health record (EHR) contains the following important information:

- History and Physical (H&P): A history and physical (H&P) is a specific type of documentation created by the health care provider when the client is admitted to the facility. An H&P includes important information about the client’s current status, medical history, and the treatment plan in a concise format that is helpful for the nurse to review. Information typically includes the reason for admission, health history, surgical history, allergies, current medications, physical examination findings, medical diagnoses, and the treatment plan.

- Provider orders: This section includes the prescriptions, or medical orders, that the nurse must legally implement or appropriately communicate according to agency policy if not implemented.

- Medication Administration Records (MARs): Medications are charted through electronic medication administration records (MARs). These records interface the medication orders from providers with pharmacists and are also the location where nurses document medications administered.

- Treatment Administration Records (TARs): In many facilities, treatments are documented on a treatment administration record.

- Laboratory results: This section includes results from blood work and other tests performed in the lab.

- Diagnostic test results: This section includes results from diagnostic tests ordered by the provider such as X-rays, ultrasounds, etc.

- Progress notes: This section contains notes created by nurses, providers, and other interprofessional team members regarding client care. It is helpful for the nurse to review daily progress notes by all team members to ensure continuity of care.

- Nursing care plans: Nursing care plans are created by registered nurses (RNs). Documentation of individualized nursing care plans is legally required in long-term care facilities by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and in hospitals by The Joint Commission. Nursing care plans are individualized to meet the specific and unique needs of each client. They contain expected outcomes and planned interventions to be completed by nurses and other members of the interprofessional team. As part of the nursing process, nurses routinely evaluate the client’s progress toward meeting the expected outcomes and modify the nursing care plan as needed. Read more about nursing care plans in the “Planning” section of the “Nursing Process” chapter in Open RN Nursing Fundamentals.

Applied Learning Activity Communication Style Inventory

add additional content here

IPEC Competency 4: Teams and Teamwork

Now that we have reviewed the first three IPEC competencies related to valuing team members , understanding team members’ roles and responsibilities and interprofessional communication, let’s discuss strategies that promote effective teamwork. The fourth IPEC competency states, “Apply relationship-building values and the principles of team dynamics to perform effectively in different team roles to plan, deliver, and evaluate patient/population-centered care and population health programs and policies that are safe, timely, efficient, effective, and equitable” (Interprofessional Education Collaborative, n.d.). See the following box for the components of this IPEC competency.

Components of IPEC’s Teams and Teamwork Competency (Interprofessional Education Collaborative, n.d.)

- Describe the process of team development and the roles and practices of effective teams.

- Develop consensus on the ethical principles to guide all aspects of teamwork.

- Engage health and other professionals in shared patient-centered and population-focused problem-solving.

- Integrate the knowledge and experience of health and other professions to inform health and care decisions, while respecting patient and community values and priorities/preferences for care.

- Apply leadership practices that support collaborative practice and team effectiveness.

- Engage self and others to constructively manage disagreements about values, roles, goals, and actions that arise among health and other professionals and with patients, families, and community members.

- Share accountability with other professions, patients, and communities for outcomes relevant to prevention and health care.

- Reflect on individual and team performance for individual, as well as team, performance improvement.

- Use process improvement to increase effectiveness of interprofessional teamwork and team-based services, programs, and policies.

- Use available evidence to inform effective teamwork and team-based practices.

- Perform effectively on teams and in different team roles in a variety of settings.

Developing effective teams is critical for providing health care that is patient-centered, safe, timely, effective, efficient, and equitable (Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel, 2011). See Figure 3.2 (Flamingo Images, n.d.) for an image illustrating interprofessional teamwork.

Nurses collaborate with the interprofessional team by not only assigning and coordinating tasks, but also by promoting solid teamwork in a positive environment. A nursing leader, such as a charge nurse, identifies gaps in workflow, recognizes when task overload is occurring, and promotes the adaptability of the team to respond to evolving patient conditions. Qualities of a successful team are described in the following box (O'Daniel & Rosenstein, 2011).

Qualities of A Successful Team (O'Daniel & Rosenstein, 2011)

- Promote a respectful atmosphere

- Define clear roles and responsibilities for team members

- Regularly and routinely share information

- Encourage open communication

- Implement a culture of safety

- Provide clear directions

- Share responsibility for team success

- Balance team member participation based on the current situation

- Acknowledge and manage conflict

- Enforce accountability among all team members

- Communicate the decision-making process

- Facilitate access to needed resources

- Evaluate team outcomes and adjust as needed

STEP Tool

STEP is a tool for monitoring the delivery of health care (See Figure 3.4).

STEP Tool (AHRQ, 2020)

Status of Patients: “What is going on with your patients?”

- Patient History

- Vital Signs

- Medications

- Physical Exam

- Plan of Care

- Psychosocial Issues

Team Members: “What is going on with you and your team?”(See the “I’M SAFE Checklist” below.)

- Fatigue

- Workload

- Task Performance

- Skill

- Stress

Environment: Knowing Your Resources

- Facility Information

- Administrative Information

- Human Resources

- Triage Acuity

- Equipment

Progression Towards Goal:

- Status of the Team's Patients

- Established Goals of the Team

- Tasks/Actions of the Team

- Appropriateness of the Plan - Are Modifications Needed?

Cross Monitoring

As the STEP tool is implemented, the team leader continues to cross monitor to reduce the incidence of errors. Cross monitoring includes the following (AHRQ, 2020):

- Monitoring the actions of other team members.

- Providing a safety net within the team.

- Ensuring that mistakes or oversights are caught quickly and easily.

- Supporting each other as needed.

I’M SAFE Checklist

The I’M SAFE mnemonic is a tool used to assess one’s own safety status, as well as that of other team members in their ability to provide safe patient care. See the I’M SAFE Checklist in the following box (AHRQ, 2020). If a team member feels their ability to provide safe care is diminished because of one of these factors, they should notify the charge nurse or other nursing supervisor. In a similar manner, if a nurse notices that another member of the team is impaired or providing care in an unsafe manner, it is an ethical imperative to protect clients and report their concerns according to agency policy (AHRQ, 2020).

I'm SAFE Checklist (AHRQ, 2020)

- I: Illness

- M: Medication

- S: Stress

- A: Alcohol and Drugs

- F: Fatigue

- E: Eating and Elimination

Read an example of a nursing team leader performing situation monitoring using the STEP tool in the following box.

Example of Situation Monitoring

Two emergent situations occur simultaneously on a busy medical-surgical hospital unit as one patient codes and another develops a postoperative hemorrhage. The charge nurse is performing situation monitoring by continually scanning and assessing the status of all patients on the unit and directing additional assistance where it is needed. Each nursing team member maintains situation awareness by being aware of what is happening on the unit, in addition to caring for the patients they have been assigned. The charge nurse creates a shared mental model by ensuring all team members are aware of their evolving responsibilities as the situation changes. The charge nurse directs additional assistance to the emergent patients while also ensuring appropriate coverage for the other patients on the unit to ensure all patients receive safe and effective care.

For example, as the “code” is called, the charge nurse directs two additional nurses and two additional assistive personnel to assist with the emergent patients while the other nurses and assistive personnel are directed to “cover” the remaining patients, answer call lights, and assist patients to the bathroom to prevent falls. Additionally, the charge nurse is aware that after performing a few rounds of CPR for the coding patient, the assistive personnel must be switched with another team member to maintain effective chest compressions. As the situation progresses, the charge nurse evaluates the status of all patients and makes adjustments to the plan as needed.

Mutual Support

Mutual support is the fourth skill of the TeamSTEPPS® framework and defined as the “ability to anticipate and support team members' needs through accurate knowledge about their responsibilities and workload” (AHRQ, 2020). Mutual support includes providing task assistance, giving feedback, and advocating for patient safety by using assertive statements to correct a safety concern. Managing conflict is also a component of supporting team members’ needs.

Task Assistance

Helping other team members with tasks builds a strong team. Task assistance includes the following components (AHRQ, 2020):

- Team members protect each other from work-overload situations.

- Effective teams place all offers and requests for assistance in the context of patient safety.

- Team members foster a climate where it is expected that assistance will be actively sought and offered.

Example of Task Assistance

In a previous example, one patient on the unit was coding while another was experiencing a postoperative hemorrhage. After the emergent care was provided and the hemorrhaging patient was stabilized, Sue, the nurse caring for the hemorrhaging patient, finds many scheduled medications for her other patients are past due. Sue reaches out to Sam, another nurse on the team, and requests assistance. Sam agrees to administer a scheduled IV antibiotic to a stable third patient so Sue can administer oral medications to her remaining patients. Sam knows that on an upcoming shift, he may need to request assistance from Sue when unexpected situations occur. In this manner, team members foster a climate where assistance is actively sought and offered to maintain patient safety.

Feedback

Feedback is provided to a team member for the purpose of improving team performance. Effective feedback should follow these parameters (AHRQ, 2020):

- Timely: Provided soon after the target behavior has occurred.

- Respectful: Focused on behaviors, not personal attributes.

- Specific: Related to a specific task or behavior that requires correction or improvement.

- Directed towards improvement: Suggestions are made for future improvement.

- Considerate: Team members’ feelings should be considered and privacy provided. Negative information should be delivered with fairness and respect

Strategies for effective communication are found in Appendix C.

Next: 3.4 Spotlight Application

Chapter References

Appendix C

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (n.d.). Elderly. https://www.ahrq.gov/topics/elderly.html

Bunis, D. (2021, June 7). Prescription drug price increases continue to outpace inflation. AARP. https://www.aarp.org/politics-society/advocacy/info-2021/prescription-price-increase-report.html

Bush, M. (2018). Addressing the root cause: Rising health care costs and social determinants of health. North Carolina Medical Journal, 79(1), 26-29. https://doi.org/10.18043/ncm.79.1.26

CMS.gov. (2020, December 16). National health expenditure data - historical. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical

“graying-america-aging-nation.jpg” by U.S. Census Bureau is in the Public Domain

“Health_Care_Cost_as_Percentage_of_GDP.png” by Delphi234 is licensed under CC0 1.0

HealthCare.gov. Insurance marketplace. https://www.healthcare.gov/subscribe/? gclid=Cj0KCQjwiqWHBhD2ARIsAPCDzamNRkS3URx_uUvJGdpX15DrZnVbBadXbPmOjBBlLyjtZBn7cLei6WEaAl8GEALw_wcB&gclsrc=aw.ds

Healthy People 2030. (n.d.). Social determinants of health. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health

HHS.gov. About the Affordable Care Act. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.hhs.gov/healthcare/about-the-aca/index.html

K&L Gates LLP, Carnevale, A., Hamscho, V., Lawless, T., & Sha Page, K. (2021, June 21). The Affordable Care Act survives Supreme Court challenge: What happens next? JD Supra. https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/the-affordable-care-act-survives-3115372/

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2021). The Future of nursing 2020-2030: Charting a path to achieve health equity. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25982

Neumann, P. J., & Weinstein, M. C. (1991). The diffusion of new technology: Costs and benefits to health care. In Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Technological Innovation in Medicine, Gelijns, A. C., & Halm, E. A. (Eds.). The changing economics of medical technology. National Academies Press. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK234309/

Peterson_KFF Health Systems Tracker. (n.d.). Health expenditures 1960-2020. https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/health-spending-explorer/?outputType=%24pop-adjusted&serviceType%5B0%5D=prescriptionDrug&serviceType%5B1%5D=hospitals&serviceType%5B2%5D=allTypes&sourceOfFunds%5B0%5D=allSources&tab=0&yearCompare%5B0%5D=%2A&yearCompare%5B1%5D=%2A&yearRange%5B0%5D=%2A&yearRange%5B1%5D=%2A&yearSingle=%2A&yearType=range

Schreck, R. I. (2020, March). Overview of health care financing. Merck Manual Consumer Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/fundamentals/financial-issues-in-health-care/overview-of-health-care-financing

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2021, March 23). 5 things about the Affordable Care Act (ACA). [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/j9tRVESzJ1M

“49458105981_fe87fd521c_o.jpg” by Wonderlane is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Next: Chapter Attribution

Patient-centered care, also known as person-centered care has become an increasingly popular term in healthcare over the last decade. This is not a new concept for nurses, as our core commitment to patients is to provide the best care possible. However, the term has grown in popularity in an attempt to meet the challenges in healthcare. As nurse leaders, person- centered care can and should extend beyond the "patient" but should also include all stakeholders, including those that are impacted by policy and leadership decisions. An essential reminder of keeping the "persons" in mind when planning will go a long way to achieving optimal outcomes (Exercise 7.1.1).

Exercise 7.1.1

Sample Questions to consider when leading person-centered decisions

- Who are our primary stakeholders?

- Who will benefit from this decision?

- Who will need to be included in this discussion?

- Why are we making this change?

- Is there another way to complete this?

- What are our priorities?

- How can we do with well?

The notion of patient-centeredness has been in the literature since the mid-20th century or earlier. For example, in 1960, the patient-centered approach was considered “a trend in modern nursing practice . . . gradually replacing the procedure-centered approach . . . as the prime concern of the nurse” (Hofling & Leininger, 1960, pp. 4-5)

Next: 7.2 Health Care Trends and Issues

Chapter References

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (n.d.). Elderly. https://www.ahrq.gov/topics/elderly.html

Bunis, D. (2021, June 7). Prescription drug price increases continue to outpace inflation. AARP. https://www.aarp.org/politics-society/advocacy/info-2021/prescription-price-increase-report.html

Bush, M. (2018). Addressing the root cause: Rising health care costs and social determinants of health. North Carolina Medical Journal, 79(1), 26-29. https://doi.org/10.18043/ncm.79.1.26

CMS.gov. (2020, December 16). National health expenditure data - historical. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical

“graying-america-aging-nation.jpg” by U.S. Census Bureau is in the Public Domain

Hofling H. K., Leininger M. M. (1960). Basic psychiatric concepts in nursing. Philadelphia, PA: J. B. Lippincott.

“Health_Care_Cost_as_Percentage_of_GDP.png” by Delphi234 is licensed under CC0 1.0

HealthCare.gov. Insurance marketplace. https://www.healthcare.gov/subscribe/? gclid=Cj0KCQjwiqWHBhD2ARIsAPCDzamNRkS3URx_uUvJGdpX15DrZnVbBadXbPmOjBBlLyjtZBn7cLei6WEaAl8GEALw_wcB&gclsrc=aw.ds

Healthy People 2030. (n.d.). Social determinants of health. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health

HHS.gov. About the Affordable Care Act. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.hhs.gov/healthcare/about-the-aca/index.html

K&L Gates LLP, Carnevale, A., Hamscho, V., Lawless, T., & Sha Page, K. (2021, June 21). The Affordable Care Act survives Supreme Court challenge: What happens next? JD Supra. https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/the-affordable-care-act-survives-3115372/

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2021). The Future of nursing 2020-2030: Charting a path to achieve health equity. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25982

Neumann, P. J., & Weinstein, M. C. (1991). The diffusion of new technology: Costs and benefits to health care. In Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Technological Innovation in Medicine, Gelijns, A. C., & Halm, E. A. (Eds.). The changing economics of medical technology. National Academies Press. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK234309/

Peterson_KFF Health Systems Tracker. (n.d.). Health expenditures 1960-2020. https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/health-spending-explorer/?outputType=%24pop-adjusted&serviceType%5B0%5D=prescriptionDrug&serviceType%5B1%5D=hospitals&serviceType%5B2%5D=allTypes&sourceOfFunds%5B0%5D=allSources&tab=0&yearCompare%5B0%5D=%2A&yearCompare%5B1%5D=%2A&yearRange%5B0%5D=%2A&yearRange%5B1%5D=%2A&yearSingle=%2A&yearType=range

Schreck, R. I. (2020, March). Overview of health care financing. Merck Manual Consumer Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/fundamentals/financial-issues-in-health-care/overview-of-health-care-financing

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2021, March 23). 5 things about the Affordable Care Act (ACA). [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/j9tRVESzJ1M

“49458105981_fe87fd521c_o.jpg” by Wonderlane is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Next: Chapter Attribution

Quality is defined in a variety of ways that impact nursing practice.

American Nurses Association Definition of Quality

The American Nurses Association (ANA) defines quality as, “The degree to which nursing services for health care consumers, families, groups, communities, and populations increase the likelihood of desirable outcomes and are consistent with evolving nursing knowledge” (ANA, 2021). The phrases in this definition focus on three aspects of quality: services (nursing interventions), desirable outcomes, and consistency with evolving nursing knowledge (evidence-based practice). Alignment of nursing interventions with current evidence-based practice is a key component for quality care (Stevens, 2013). Evidence-based practice (EBP) will be further discussed later in this chapter.

Quality of Practice is one of the ANA’s Standards of Professional Performance. ANA Standards of Professional Performance are “authoritative statements of the actions and behaviors that all registered nurses, regardless of role, population, specialty, and setting are expected to perform competently." See the competencies for the ANA’s Quality of Practice Standard of Professional Performance in the following box (ANA, 2021).

Competencies of ANA’s Quality of Practice Standard of Professional Performance (ANA, 2021)

- Ensures that nursing practice is safe, effective, efficient, equitable, timely, and person-centered.

- Incorporates evidence into nursing practice to improve outcomes.

- Uses creativity and innovation to enhance nursing care.

- Recommends strategies to improve nursing care quality.

- Collects data to monitor the quality of nursing practice.

- Contributes to efforts to improve health care efficiency.

- Provides critical review and evaluation of policies, procedures, and guidelines to improve the quality of health care.

- Engages in formal and informal peer review processes of the interprofessional team.

- Participates in quality improvement initiatives.

- Collaborates with the interprofessional team to implement quality improvement plans and interventions.

- Documents nursing practice in a manner that supports quality and performance improvement initiatives.

- Recognizes the value of professional and specialty certification.

Learning Exercise 4.2.1

Answer the following reflective questions about the Quality of Practice:

- What Quality of Practice competencies have you already demonstrated during your nursing education?

- What Quality of Practice competencies are you most interested in mastering?

- What questions do you have about the ANA’s Quality of Practice competencies? Where could you find answers to those questions (e.g., instructors, preceptors, health care team members, guidelines, or core measures)?

Quality and Safety Education for Nurses

The Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN) project advocates for safe, quality patient care by defining six competencies for prelicensure nursing students: Patient-Centered Care, Teamwork and Collaboration, Evidence-Based Practice, Quality Improvement, Safety, and Informatics. As licensed Registered Nurses, you are likely applying these competencies in your nursing practice. Consider how attainment of a Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) will advance your nursing practice in use of the QSEN competencies.

Framework of Quality Health Care

A definition of quality that has historically guided the measurement of quality initiatives in health care systems is based on the framework for improvement originally created by the Institute of Medicine (IOM). The IOM name changed to the National Academy of Medicine in 2015. The IOM framework includes the following six criteria for defining quality health care (Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality, 2015; Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, 2001):

- Safe: Avoiding harm to patients from the care that is intended to help them.

- Effective: Providing services based on scientific knowledge to all who could benefit and refraining from providing services to those not likely to benefit (i.e., avoiding underuse and misuse).

- Patient-centered: Providing care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions.

- Timely: Reducing waits and sometimes harmful delays for both those who receive and those who provide care.

- Efficient: Avoiding waste, including waste of equipment, supplies, ideas, and energy.

- Equitable: Providing care that does not vary in quality because of personal characteristics such as gender, ethnicity, geographic location, and socioeconomic status.

This framework continues to guide quality improvement initiatives across America’s health care system. The evidence-based practice (EBP) movement began with the public acknowledgement of unacceptable patient outcomes resulting from a gap between research findings and actual health care practices. For EBP to be successfully adopted and sustained, it must be adopted by nurses and other health care team members, system leaders, and policy makers. Regulations and recognitions are also necessary to promote the adoption of EBP. For example, the Magnet Recognition Program promotes nursing as a leader in catalyzing adoption of EBP and using it as a marker of excellence (Stevens, 2013).

Reimbursement Models

Quality health care is also defined by value-based reimbursement models used by Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurance companies paying for health services. Value-based payment reimbursement models use financial incentives to reward quality health care and positive patient outcomes. For example, Medicare no longer reimburses hospitals to treat patients who acquire certain preventable conditions during their hospital stay, such as pressure injuries or urinary tract infections associated with use of catheters (James, 2012). These reimbursement models directly impact the evidence-based care nurses provide at the bedside and the associated documentation of assessments, interventions, and nursing care plans to ensure quality performance criteria are met.

CMS Quality Initiatives

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) establishes quality initiatives that focus on several key quality measures of health care. These quality measures provide a comprehensive understanding and evaluation of the care an organization delivers, as well as patients’ responses to the care provided. These quality measures evaluate many areas of health care, including the following (CMS.gov, 2020):

- Health outcomes

- Clinical processes

- Patient safety

- Efficient use of health care resources

- Care coordination

- Patient engagement in their own care

- Patient perceptions of their care

These measures of quality focus on providing the care the patient needs when the patient needs it, in an affordable, safe, effective manner. It also means engaging and involving the patient so they take ownership in managing their care at home.

Learn More

Visit the CMS What is a Quality Measure webpage.

Accreditation

Accreditation is a review process that determines if an agency is meeting the defined standards of quality determined by the accrediting body. The main accrediting organizations for health care are as follows:

- The Joint Commission

- National Committee for Quality Assurance

- American Medical Accreditation Program

- American Accreditation Healthcare Commission

The standards of quality vary depending on the accrediting organization, but they all share common goals to improve efficiency, equity, and delivery of high-quality care. Two terms commonly associated with accreditation that are directly related to quality nursing care are core measures and patient safety goals.

Core Measures

Core measures are national standards of care and treatment processes for common conditions. These processes are proven to reduce complications and lead to better patient outcomes. Core measure compliance reports show how often a hospital successfully provides recommended treatment for certain medical conditions. In the United States, hospitals must report their compliance with core measures to The Joint Commission, CMS, and other agencies (John Hopkins Medicine, n.d.).

In November 2003, The Joint Commission and CMS began work to align common core measures so they are identical. This work resulted in the creation of one common set of measures known as the Specifications Manual for National Hospital Inpatient Quality Measures. These core measures are used by both organizations to improve the health care delivery process. Examples of core measures include guidelines regarding immunizations, tobacco treatment, substance use, hip and knee replacements, cardiac care, strokes, treatment of high blood pressure, and the use of high-risk medications in the elderly. Nurses must be aware of core measures and ensure the care they provide aligns with these recommendations (The Joint Commission, n.d.).

Learn More

Read more about the National Hospital Inpatient Quality Measures.

Patient Safety Goals

Patient safety goals are guidelines specific to organizations accredited by The Joint Commission that focus on health care safety problems and ways to solve them. The National Patient Safety Goals (NPSG) were first established in 2003 and are updated annually to address areas of national concern related to patient safety, as well as to promote high-quality care. The NPSG provide guidance for specific health care settings, including hospitals, ambulatory clinics, behavioral health, critical access hospitals, home care, laboratory, skilled nursing care, and surgery.

The following goals are some examples of NPSG for hospitals (The Joint Commission, 2022):

- Identify patients correctly

- Improve staff communication

- Use medicines safely

- Use alarms safely

- Prevent infection

- Identify patient safety risks

- Prevent mistakes in surgery

Nurses must be aware of the current NPSG for their health care setting, implement appropriate interventions, and document their assessments and interventions. Documentation in the electronic medical record is primarily used as evidence that an organization is meeting these goals.

Learn More

Read the current agency-specific National Patient Safety Goals.