Pests and Pesticides

Pests are organisms that occur where they are not wanted or that cause damage to crops or humans, or other animals. Thus, the term “pest” is highly subjective. A pesticide is a term for any substance intended for preventing, destroying, repelling, or mitigating any pest. Though often misunderstood to refer only to insecticides, pesticides also apply to herbicides, fungicides, and other substances used to control pests. By their very nature, most pesticides create some risk of harm—pesticides can cause harm to humans, animals, and/or the environment because they are designed to kill or otherwise adversely affect living things. At the same time, pesticides are useful to society because they can kill potential disease-causing organisms and control insects, weeds, worms, and fungi.

Pest Control is a Common Tool

Managing pests is essential to agriculture, public health, and maintaining power lines and roads. Chemical pest management has helped to reduce losses in agriculture and to limit human exposure to disease vectors, such as mosquitoes, saving many lives. Chemical pesticides can be effective, fast acting, and adaptable to all crops and situations. When first applied, pesticides can result in impressive production gains for crops. However, despite these initial gains, excessive use of pesticides can be ecologically unsound, leading to the destruction of natural enemies, increased pesticide resistance, and outbreaks of secondary pests.

These consequences have often resulted in higher production costs and environmental and human health costs– side effects that have been unevenly distributed. Despite the lion’s share of chemical pesticides being applied in developed countries, 99 percent of all pesticide poisoning cases occur in developing countries where regulatory, health, and education systems are weakest. Many farmers in developing countries overuse pesticides and do not take proper safety precautions because they do not understand the risks and fear smaller harvests. Making matters worse, developing countries seldom have strong regulatory systems for dangerous chemicals; pesticides banned or restricted in industrialized countries are used widely in developing countries. Farmers’ perceptions of appropriate pesticide use vary by setting and culture. Prolonged pesticide exposure has been associated with several chronic and acute health effects, like non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and leukemia, cardiopulmonary disorders, neurological and hematological symptoms, and skin diseases.

|

BOX 1. HUMAN HEALTH, ENVIRONMENTAL, AND ECONOMIC EFFECTS OF PESTICIDE USE IN POTATO PRODUCTION IN ECUADOR |

|

The International Potato Center (CIP) conducted an interdisciplinary and inter-institutional research intervention project dealing with pesticide impacts on agricultural production, human health, and the environment in Carchi, Ecuador. Carchi is Ecuador’s most important potato-growing area, where smallholder farmers dominate production. They use tremendous amounts of pesticides to control the Andean potato weevil and the late blight fungus. Virtually all farmers apply to class 1b highly toxic pesticides using hand pump backpack sprayers. The study found that the health problems caused by pesticides are severe and are affecting a high percentage of the rural population. Despite the existence of technology and policy solutions, government policies continue to promote the use of pesticides. The study conclusions concurred with those of the pesticide industry, “that any company that could not ensure the safe use of highly toxic pesticides should remove them from the market and that it is almost impossible to achieve safe use of highly toxic pesticides among small farmers in developing countries.” Source: Yanggen et al. 2003. |

POPs

Persistent organic pollutants (POPs) are a group of organic chemicals, such as DDT, widely used as pesticides or industrial chemicals and pose risks to human health and ecosystems. POPs have been produced and released into the environment by human activity. They have the following three characteristics:

Persistent: POPs are chemicals that last a long time in the environment. Some may resist breakdown for years and even decades, while others could potentially break down into other toxic substances.

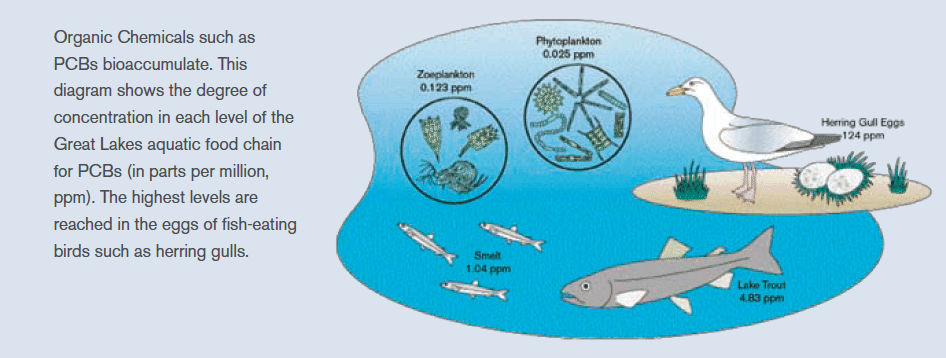

Bioaccumulative: POPs can accumulate in animals and humans, usually in fatty tissues and largely from the food they consume. As these compounds move up the food chain, they concentrate to levels that could be thousands of times higher than acceptable limits.

Toxic: POPs can cause various health effects in humans, wildlife, and fish. They have been linked to effects on the nervous system, reproductive and developmental problems, immune system suppression, cancer, and endocrine disruption. The deliberate production and use of most POPs have been banned worldwide, with some exemptions made for human health considerations (e.g., DDT for malaria control) and/or in very specific cases where alternative chemicals have not been identified. However, the unintended production and/or the current use of some POPs continue to be an issue of global concern. Even though most POPs have not been manufactured or used for decades, they continue to be present in the environment and thus potentially harmful. The same properties that originally made them so effective, particularly their stability, make them difficult to eradicate from the environment.

POPs and Health

The relationship between exposure to environmental contaminants such as POPs and human health is complex. There is mounting evidence that these persistent, bioaccumulation, and toxic chemicals (PBTs) cause long-term harm to human health and the environment. Drawing a direct link, however, between exposure to these chemicals and health effects is complicated, particularly since humans are exposed daily to many different environmental contaminants through the air they breathe, the water they drink, and the food they eat. Numerous studies link POPs with a number of adverse effects in humans. These include effects on the nervous system, problems related to reproduction and development, cancer, and genetic impacts. Moreover, there is mounting public concern over the environmental contaminants that mimic hormones in the human body (endocrine disruptors).

As with humans, animals are exposed to POPs in the environment through air, water, and food. POPs can remain in sediments for years, where bottom-dwelling creatures consume them and are then eaten by larger fish. Because tissue concentrations can increase or biomagnify at each food chain level, top predators (like largemouth bass or walleye) may have a million times greater concentrations of POPs than the water itself. The animals most exposed to PBT contaminants are those higher up the food web, such as marine mammals, including whales, seals, polar bears, and birds of prey and fish species, such as tuna, swordfish, and bass (Figure 2). Once POPs are released into the environment, they may be transported within a specific region and across international boundaries transferring among air, water, and land.

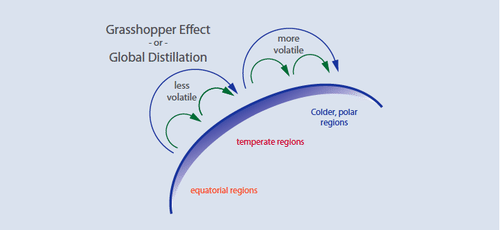

“Grasshopper Effect”

While generally banned or restricted, POPs make their way into and throughout the environment daily through a cycle of long-range air transport and deposition called the “grasshopper effect.”The “grasshopper” processes, illustrated in Figure 3, begin with releasing POPs into the environment. When POPs enter the atmosphere, they can be carried by wind currents, sometimes for long distances.

They are deposited onto land or into water ecosystems through atmospheric processes, where they accumulate and potentially cause damage. From these ecosystems, they evaporate, again entering the atmosphere, typically traveling from warmer temperatures toward cooler regions. They condense out of the atmosphere whenever the temperature drops, eventually reaching the highest concentrations in circumpolar countries. Through these processes, POPs can move thousands of kilometers from their original release source in a cycle that may last decades.