4 Chapter 4: Instructional Resources

- Instructional Strategy

- Instructional Resources

- Learning Resources

- Resources for Open Education Materials

- Adapt or adopt the Content?

- Finding, Evaluating, and Adapting Resources

In this chapter of the book, you will be introduced to the instructional strategies (or instructional resources ) in design lessons.

Materials to support lesson planning: Instructional Materials Video

Instructional Strategy

An instructional strategy describes the instructional materials and procedures that enable students to achieve the learning outcomes. Your instructional strategy should describe the instructional materials’ components and procedures used with the materials that are needed for students to achieve the learning outcomes. The strategy should be based on the learning outcomes. You can save time and money by not reinventing the wheel. However, be careful; a lot of existing instructional material is designed poorly.

Use the instructional strategy as a framework for further developing the instructional materials or evaluating whether existing materials are suitable or need revision. As a general rule, use the strategy to set up a framework for maximizing effective and efficient learning. This often requires using strategies that go beyond basic teaching methods. For example, discovery-learning techniques can be more powerful than simply presenting the facts. No single teaching method or medium is ideal for all learners. As you proceed through developing an instructional strategy, start specifying the media that would most effectively teach the material.

Learning Domain Strategies

Each of Gagne’s Domains of Learning (look back at the Analysis: the learning task chapter) is best taught with different instructional strategies.

Verbal Information

Verbal information is material, such as names of objects, that students simply have to memorize and recall.

When teaching verbal information:

- Organize the material into small, easily retrievable chunks.

- Link new information to knowledge the learner already possesses. For example, use statements such as

“Remember how”, or “This is like …”. Linking information helps the learner to store and recall the material.

- Use mnemonics and other memory devices for new information. You may recall that the musical notes of the treble clef staff lines can be remembered with the mnemonic Every Good Boy Deserves Fudge.

- Use meaningful contexts and relevant cues. For example, relating a problem to a sports car can be relevant to some members of your target audience.

- Have the learners generate examples in their minds, such as creating a song or game with the information or applying the knowledge to the real world. If the student only memorizes facts then the learning will only have minimal value.

- Avoid rote repetition as a memorization aid. Rote learning has minimal effectiveness over time.

- Provide visuals to increase learning and recall.

Intellectual Skills

Intellectual skills are those that require learners to think (rather than simply memorizing and recalling information).

When teaching intellectual skills:

- Base the instructional strategy and sequencing on the hierarchical analysis done earlier. Always teach subordinate skills before higher-level skills.

- Link new knowledge to previously learned knowledge. You can do this explicitly (e.g., the bones in your feet are comparable to the bones you learned about in your hands) or implicitly (e.g., compare the bones in your feet to other bone structures you have learned about).

- Use memory devices like acronyms, rhymes, or imagery for information such as rules or principles. You can use the first letters of words to help memorize information. For example, “KISS” means “Keep It Simple Stupid”. General rules can often be remembered through rhymes such as “i before e except after c”. Remember that rules often have exceptions. Tell your learners about the exceptions. Memory devices are best for limited amounts of information.

- Use examples and non-examples that are familiar to the student. For instance, when classifying metals, iron and copper are examples, while glass and plastic are non-examples.

- Use discovery-learning techniques. For example, let students manipulate variables and see the consequences.

- Use analogies that the learners know. However, be careful that learners do not over-generalize or create misconceptions.

- Provide for practice and immediate feedback.

Psychomotor Skills

Psychomotor skills are those that require learners to carry out muscular actions.

When teaching psychomotor skills:

- Base the instructional strategy on the procedural analysis done earlier.

- Provide directions for completing all of the steps.

- Provide repeated practice and feedback for individual steps, then groups of steps, and then the entire sequence.

- Remember that, in general, practice should become less dependent on written or verbal directions.

- Consider visuals to enhance learning.

- Consider job aids, such as a list of steps, to reduce memory requirements. This is especially important if there are many procedures or if the procedures are infrequently used.

- After a certain point, allow learners to interact with real objects or do the real thing. How much can you learn about swimming without getting wet?

Note that some skills involve other learning-domain classifications. For example, when learning how to operate a camcorder, many of the skills are psychomotor. However, deciding how to light an image is an intellectual skill. Also, note that the required proficiency level can affect the instructional strategy. There is a big difference between being able to imitate a skill and being able to automatically do a skill.

Attitudes

Attitudes involve how a student feels about the instruction whether they will value or care about the material presented to them.

When teaching attitudes:

- Base the instructional strategy on the instructional design steps done earlier.

- If you can, show a human model to which the students can easily relate. One consideration is that it may be better if the model is of the same socioeconomic group.

- Show realistic consequences for appropriate and inappropriate choices.

- Consider using video.

- Remember that attitudes taught through computer technology are not guaranteed to transfer to the real world. If appropriate and possible, consider arranging for practice opportunities to make the choice in real life. Alternatively, use role-playing to reinforce the attitudes taught.

Note that it can be difficult to test whether the attitudes taught have transferred to real situations. Will learners behave naturally if they know that they are being observed? If learners have not voluntarily permitted observations, then you must consider whether it is ethical to make the observations.

Sequencing Learning Outcomes

Using your needs and learning task analysis, determine the sequence of how the learning outcomes will be taught. In general, to best facilitate learning, you should sequence the learning outcomes from:

- easy to hard

- You could teach adding fractions with common denominators and then with different denominators. Your lesson could first deal with writing complete sentences and then writing paragraphs.

- simple to complex

- As an example, first teach students to recognize weather patterns and then use what they have learned to predict the weather.

- Cover replacing a washer and then replacing a faucet.

- specific to general

- You could teach driving a specific car and then transfer the skills to driving any car. Similarly, you could cover adjusting the brakes on a specific mountain bike and then generalize the procedure to other mountain bikes

- Note that some students like to learn through an inductive approach (that is, from the general to the specific). For example, students could be presented with a number of simple examples, and based on those, be asked to generalize a rule. That general rule can then be applied to solving specific examples. Since some students will not enjoy an inductive approach, do not use it all of the time. Rather consider an inductive approach as a way to provide some variation and occasionally address other learning preferences.

- concrete to abstract

- As an example, teach measuring distances with a tape measure and then estimating distances without a tape measure. Cover writing learning outcomes and then evaluating learning outcomes.

- the known to the unknown

- You could do this by starting with concepts learners already know and extending those concepts to new ideas. In other words, build on what has been previously taught.

Each of these methods of sequencing learning outcomes enables students to acquire the needed knowledge base for learning higher-level skills. Note that these guidelines are not black-and-white rules.

Motivating Students

As Lao Tzu observed, “You can no more teach without the learner than a merchant can sell without a willing buyer.” Follow the ARCS motivation model to ensure that students will be motivated to learn.

ARCS Motivational Model

As described by Keller, motivation can be enhanced through addressing the four attributes of Attention, Relevance, Confidence, and Satisfaction (ARCS). Try to include all of the attributes since each alone may not maintain student motivation. Your learner analysis may have provided useful information for motivating students. You should build motivational strategies into the materials throughout the lesson design process. This is challenging since each learner is an individual with unique interests, experiences, and goals.

Attention

Gain attention and then sustain it. You can gain attention by using human-interest examples, arousing emotions such as by showing a peer being wheeled into an ambulance, presenting personal information, challenging the learner, providing an interesting problem to solve, arousing the learner’s curiosity, showing exciting video or animation sequences, stating conflicting information, using humor, asking questions, and presenting a stimulus change that can be as simple as an audio beep. One way to sustain attention is by making the learning highly interactive.

Relevance

Relevance helps the student to want to learn the material by helping them understand how the material relates to their needs or how it can relate to improving their future. For example, when teaching adult students how to solve percent problems, having them calculate the gratuity on a restaurant bill may be more relevant than a problem that compares two people’s ages. You can provide relevance through testimonials, illustrative stories, simulations, practical applications, personal experience, and relating the material to present or future values or needs. Relevance is also useful in helping to sustain attention. For material to be perceived as being relevant, you must strive to match the learner’s expectations to the material you provide.

Confidence

If students are confident that they can master the material, they will be much more willing to attempt the instruction. You will need to convince students with low confidence that they can be successful. You can do this by presenting the material in small, incremental steps or even by stating how other similar students have succeeded. Tasks should seem achievable rather than insurmountable. You should also convince students who are overconfident that there is material that they need to learn. You can do this by giving a challenging pre-test or presenting difficult questions.

Satisfaction

Satisfaction provides value for learning the material. Satisfaction can be intrinsic from the pleasure or value of the activity itself, extrinsic from the value or importance of the activity’s result, for social reasons such as pleasing people whose opinions are important to them, for achievement goals such as the motive to be successful or avoid failure, or a combination of these. Examples of intrinsic satisfaction include the joy or challenge of learning, increased confidence, positive outcomes, and increased feelings of self-worth. Examples of extrinsic satisfaction include monetary rewards, praise, a certificate, avoidance of discomfort or punishment for not doing it, and unexpected rewards. Some evidence suggests that extrinsic motivation, such as a certificate for completing a course, does not last over time. Nonetheless, it is better to assume that some students need extrinsic motivation. To be safe, try to provide your learners with both intrinsic, which should have more of the focus and extrinsic rewards. If the intrinsic motivation is high for all learners, you will not need to plan as much for extrinsic motivation. Note that satisfaction can be provided by enabling learners to apply the skills they have gained in a meaningful way. Remember to let the students know that the material to be learned is important. Consider increasing extrinsic motivation through quizzes and tests.

Watch the video:

ARCS The Movie – How to Motivate Students with the ARCS Model

Develop and Select Instructional Materials

Based on the instructional strategy for each learning outcome and information from the other steps of the lesson design process, you need to determine whether materials should be gathered or developed. The main reason for using existing materials (those owned by your institution or purchased) is to save time and money.

Gather Existing Material

Some but likely not all of the needed material may exist. Learning-object repositories may be found within your institution or at provincial/state, national, and international sites. Compare any existing material to the instructional strategy. Determine whether it is suitable and cost-effective. Determine whether the existing material can be adapted or supplemented. The alternative is to get permission to repurpose existing materials for your own needs. Remember, if you include work done by others, you have the proper permissions and have researched all copyrights regarding the material you have selected.

Develop The Needed Material

The instructional strategy of the materials you develop should consider the learning domain, motivational techniques, each phase of instruction, and all of the information gained through the lesson design process. It is wise to create a paper-based version (storyboard) of what will appear on each screen that a student will see. See the Storyboarding section of this chapter for more information. Storyboards are easier to review and edit than content within a learning management system.

Based on the storyboard, make final decisions about the media needed to effectively teach the material. These decisions are based on what will most effectively teach the material as well as practical considerations such as cost and available expertise. Once you make the decisions, start creating the media. You must consider the file formats that will be used and where the media will be stored, such as DVD-ROM, CD-ROM, Internet, or intranet.

A final storyboard must be created for the person who transfers the material to the learning management system. An accurate storyboard will reduce the number of subsequent revisions needed. After you develop the media, individual pieces can be incorporated into the system. After this, you can begin the final formative evaluation. The components of a complete instructional multimedia package can also include:

- an easy-to-use student manual with directions, strategies, learning outcomes, and summaries

- remedial and enrichment material

- an easy-to-use instructor’s manual

An instructional strategy should describe the instructional materials’ components and the procedures used with the materials needed for students to achieve the learning outcomes. Your instructional strategy should be based on your instructional analysis, the learning outcomes, and other previous instructional design steps or on how others have solved similar problems. At the end of this process, you should have a clear set of specifications describing how the material will be taught. You will use the instructional strategy as a framework for further developing the instructional materials or evaluating whether existing materials are suitable or need revision. Consider strategies that go beyond basic teaching methods. Remember that you can address a variety of learning styles if you teach with a variety of different methods and media. No single teaching method or medium is perfect for all learners. As you proceed through developing an instructional strategy, start specifying the media that would most effectively teach the material.

Each learning domain classification is best taught with different instructional strategies.

When teaching verbal information:

- Organize the material into small, easily retrievable chunks based on a cluster analysis done earlier.

- Link new information to knowledge the learner already possesses.

- Use memory devices like forming images or using mnemonics for new information.

- Use meaningful contexts and relevant cues.

- Have the learners generate examples in their minds, do something with the information, or apply the knowledge to the real world.

- Avoid rote repetition as a memorization aid.

- Provide visuals to increase learning and recall.

When teaching intellectual skills:

- Base the instructional strategy and sequencing on a hierarchical analysis done earlier.

- Link new knowledge to previously learned knowledge.

- Use memory devices like forming images or mnemonics for new information.

- Use examples and non-examples that are familiar to the student.

- Use discovery-learning techniques.

- Use analogies that the learners know.

- Provide for practice and immediate feedback.

When teaching psychomotor skills:

- Base the instructional strategy on a procedural analysis done earlier.

- Provide directions for completing all of the steps.

- Provide repeated practice and feedback for individual steps, then groups of steps, and then the entire sequence.

- Remember that, in general, practice should become less dependent on written or verbal directions.

- Consider visuals to enhance learning.

- Consider job aids, such as a list of steps, to reduce memory requirements.

- Allow learners to interact with real objects or do the real thing.

When teaching attitudes:

- Base the instructional strategy on the instructional analysis done earlier.

- If you can, show a human model to which the students can easily relate.

- Show realistic consequences for appropriate and inappropriate choices.

- Consider using video.

- Remember that attitudes taught through computer technology might not transfer to the real world.

- Note that it can be difficult to test whether the attitudes taught have transferred to real situations.

Based on the subordinate skills analysis, sequence the learning outcomes from lower to higher level skills, easy to hard, simple to complex, specific to general, concrete to abstract, and/or the known to the unknown.

It is important for your lessons to motivate learners because without motivation learning is unlikely to occur. Regular and ongoing instructor/teacher presence, especially when students are studying partly or wholly online, is essential for student success. This means effective communication between teacher/instructor and students. It is particularly important to encourage inter-student communication, either face-to-face or online. Motivation can be enhanced through addressing these attributes: Attention, Relevance, Confidence, and Satisfaction (ARCS).

Try to include all of the attributes since each alone may not maintain student motivation. You should build motivational strategies into the materials throughout the instructional design process.

- To gain attention, involve and motivate the students. Do this throughout the lesson.

- Inform the student of the learning outcome before major learning occurs to help them focus their efforts.

- Stimulate recall of prerequisites by stating the needed prerequisite skills or giving a pre-test.

- When presenting the material, sequence the material in increasing difficulty and in small incremental steps. Use a variety of methods to maintain interest. Provide examples that are meaningful, relevant, and realistic. Base some of the content on the potential for making mistakes. The proportional amount of effort needed to cover a learning outcome should be based on the learning outcome’s frequency, importance, and difficulty.

- While presenting the material, provide learning guidance to help students learn the material.

- While presenting the material, elicit the performance so that learners can find out how well they are doing. Do this by asking questions or providing opportunities to practice the skill. Remember to address metacognition within this activity.

- When eliciting the performance, provide detailed feedback. Your feedback should be positive, constructive, and immediate. Your feedback should provide complete information as to why the answer and other answers are right or wrong or guide students in how to attain the stated learning outcome.

- Formally assess the student’s performance. Tests should approximate real situations. Test all learning outcomes and only the learning outcomes. Tests should be criterion-referenced.

- Enhance retention and transfer so that students retain the information and can transfer the information beyond the specific ideas presented in the lesson.

Each type of instructional activity has strengths and weaknesses depending on the problem being solved. Incorporating a variety of creative instructional approaches can help maintain student interest and motivation as well as ensure that each student occasionally has a match between their learning style and the teaching style. Many effective lessons include more than one type of instructional activity, some fun ways to learn, and social activities like collaboration and discussions.

Based on the instructional activities for each learning outcome and information from the other steps of

lesson design process, you need to determine whether materials should be gathered or developed. The main reason for using existing materials (those owned by your institution or purchased) is to save time and money.

The instructional strategy of the materials you develop should consider the learning domain, motivational techniques, each event of instruction, and all of the information gained through the design process. It is wise to create a paper-based version (storyboard) of what will appear on each screen that a student will see. Storyboards are easier to review and edit than content within a learning management system. Based on the storyboard, make final decisions about the media needed to effectively teach the material. After you develop the media, individual pieces can be incorporated into the learning management system.

Designing Learning Activities

The importance of providing students with a structure for learning and setting appropriate learning activities is probably the most important of all the steps towards quality teaching and learning, and yet the least discussed in the literature on quality assurance.

This is the most critical part of the lesson design process, especially (but not just only) for fully online students, who have neither the regular classroom structure nor campus environment for contact with the instructor and other students nor the opportunity for spontaneous questions and discussions in a face-to-face class. Regular student activities are critical for keeping all students engaged and on task, irrespective of the mode of delivery.

These can include:

- assigned readings;

- simple multiple-choice self-assessment tests of understanding with automated feedback using the computer-based testing facility within a learning management system;

- questions regarding short paragraph answers, which may be shared with other students for comparison or discussion;

- formally marked and assessed monthly assignments in the form of short essays;

- individual or group project work spaced over several weeks;

- an individual student blog or e-portfolio that enables the student to reflect on their recent learning and which may be shared with the instructor or other students;

- online discussion forums, which the instructor will need to organize and monitor.

There are many other activities that instructors can devise to keep students engaged. However, all such activities need to be clearly linked to the stated learning outcomes for the course and can be seen by students as helping them prepare for any formal assessment. If learning outcomes are focused on skills development, then the activities should be designed to give students opportunities to develop or practice such skills. These activities also need to be regularly spaced, and an estimate made of the time students will need to complete the activities. Student engagement in such activities will need to be monitored by the instructor.

It is at this point where some hard decisions may need to be made about the balance between ‘content’ and ‘activities’. Students must have at least enough time to do regular activities (other than just reading) once each week or their risk of dropping out or failing the course will increase dramatically. In particular they will need some way of getting feedback or comments on their activities, either from the instructor or from other students, so the design of the course will have to take account of the instructors’ workload as well as the students’.

Most university and college courses are overstuffed with content, and not enough consideration is given to what students need to do to absorb, apply, and evaluate such content. A very rough rule of thumb is that students should spend no more than half their time reading content and attending lectures, the rest being spent on interpreting, analyzing, or applying that content through the kinds of activities listed above. As students become more mature and more self-managed, the proportion of time spent on activities can increase, with the students themselves being responsible for identifying appropriate content that will enable them to meet the goals and criteria laid down by the instructor. However, whatever your teaching philosophy though, there must be plenty of activities with some form of feedback for online students, or they will drop like flies on a cold winter’s day.

Evaluate

The last key ‘fundamental’ of the teaching and learning process is evaluation and innovation: assessing what has been done and then looking at ways to improve on it. New tools and new approaches to teaching are constantly becoming available. They provide the opportunity to experiment a little to see if the results are better, and if we do that, we need to evaluate the impact of using a new tool or course design. It’s what professionals do. But the main reason is that teaching is like golf: we strive for perfection but can never achieve it. It’s always possible to improve, and one of the best ways of doing that is through a systematic analysis of past experience. We will discuss the evaluation process (formative and summative evaluations) later. Continuous evaluation that drives the implementation of improvements is a never-ending process, ensuring the lesson design process is effective and engaging for the student learner today and tomorrow.

Building a Strong Foundation of Course Design

The emphasis in this series of steps is on getting the fundamentals of teaching right. Regardless of what revolutionary tools or teaching approaches are being used, what we know of how people learn does not change a great deal over time, and we do know that learning is a process, and you ignore the factors that influence that process at your peril.

For learning leading to successful outcomes, it is important to remember that most students need:

- well-defined learning goals;

- instructional strategies linked with the appropriate learning domains;

- a proper sequencing of instructional events; providing a clear timetable of work based on a well-structured organization of the curriculum;

- appropriate and engaging learning activities, with regular feedback

- manageable study workloads appropriate for their conditions of learning;

- a skilled instructor; regular instructor communication and presence;

- a social environment that draws on and contributes to the knowledge and experience of other students;

- other motivated learners to provide mutual support and encouragement.

There are many different ways these criteria can be met, with many different tools.

Key Terms

Key Terms

- Instructional Strategy

describes the instructional materials and procedures that enable students to achieve the learning outcomes. - Learning Outcomes are what the student should know or be able to accomplish at the end of the course or learning unit.

- Subordinate Skills Analysis is a process for determining the skills that must be learned before performing a step

- Learning Domain Classification verbal information, intellectual skills and cognitive strategies, psychomotor skills, and attitudes.

- Verbal information is material, such as names of objects, that students simply have to memorize and recall.

- Intellectual skills are those that require learners to think (rather than simply memorizing and recalling information).

- Psychomotor skills are those that require learners to carry out muscular actions.

- Attitudes involve how a student feels about the instruction whether they will value or care about the material presented to them.

- Relevance helps the student to want to learn the material by helping them understand how the material relates to their needs or how it can relate to improving their future.

- ARCS refers to the attributes of Attention, Relevance, Confidence, and Satisfaction. The ARCS model promotes student motivation.

- Instructional Events (gaining attention, informing the learner of the learning outcome, stimulating recall of prerequisites, presenting the material, providing learning guidance, eliciting the performance, providing feedback, assessing performance, and enhancing retention and transfer) represent what should be done to ensure that learning occurs.

Key Takeaways

Key Takeaways

- Learning domain classification (i.e., verbal information, intellectual skills, cognitive strategies, psychomotor skills, and attitudes) is best taught with different instructional strategies.

- Teach learning outcomes in the order that best facilitates learning.

- The four attributes of Keller’s ARCS Motivational Model are Attention, Relevance, Confidence, and Satisfaction. Including all of the attributes may increase student motivation.

- The unique interests, experiences, and goals of each learner influence motivation.

- Instructional events include gaining attention, informing the learner of the learning outcome, stimulating recall of prerequisites, presenting the material, providing learning guidance, eliciting the performance, providing feedback, assessing performance, and enhancing retention and transfer.

- You have been tasked with designing a university orientation course for freshmen community college students. Everyone at the institution is aware that students feel an orientation course is not necessary and that it is a waste of their time. Explain what portion of the ARCS Motivational Model might be applied to the design of the course to help students understand why this course is important for their success.

- You have been tasked with designing a university orientation course for freshmen community college students. Everyone at the institution is aware that students feel an orientation course is not necessary and that it is a waste of their time. Explain what portion of the ARCS Motivational Model might be applied to the design of the course to help students understand why this course is important for their success.

Exercises

Exercise

You have been tasked with designing Parent Night Orientation for an elementary school. Everyone at the school is aware that parents feel an orientation night is not necessary and that it is a waste of their time. Explain what portion of the ARCS Motivational Model might be applied to the design of the orientation night to help parents and staff understand why this course is important for student success.

Sources:

- Experiential Learning in Instructional Design and Technology, Chapter 3.2 Instructional Strategies by Joshua Hill and Linda Jordan is used under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

- Instructional Strategies is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license by John Raible.

- Experiential Learning in Instructional Design and Technology, Chapter 3.2 Instructional Strategies. Provided by: the authors under an Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license.

- Teaching in a Digital Age by Bates, A. W. is used under a CC-BY-NC 4.0 International license.

- Education for a Digital World: Advice, Guidelines and Effective Practice from Around the Globe by BCcampus and the Commonwealth of Learning and is used under a CC-BY-SA 3.0 International license.

Learning Resources

Learning Resources Materials are materials that are used for teaching a course.

Below are definitions of the Material Types that can be selected during the upload process for both the “Primary Material Type” field and the “Secondary/Other Material Type” field.

- Animation: Successive drawings that create an illusion of movement when shown in sequence. The animations visually and dynamically present concepts, models, processes, and/or phenomena in space or time. Users can control their pace and movement through the material typically, but they cannot determine and/or influence the initial conditions or their outcomes/results. Animations typically do not contain real people, places, or things in movement.

- Assessment Tool: Forms, templates, and technologies for measuring performance.

- Assignment: Activities or lesson plans designed to enable students to learn skills and knowledge.

- Case Study: A narrative resource describing a complex interaction of real-life factors to help illustrate the impact and/or interactions of concepts and factors in depth.

- Collection: A meaningful organization of learning resources, such as websites, documents, apps, etc., that provides users with an easier way to discover the materials.

- Development Tool: Software development applications platforms for authoring technology-based resources (e.g. web sites, learning objects, apps.).

- Drill and Practice: Requires users to respond repeatedly to questions or stimuli presented in a variety of sequences. Users practice on their own, at their own pace, to develop their ability to reliably perform and demonstrate the target knowledge and skills.

- ePortfolio: A collection of electronic materials assembled and managed by a user. These may include text, electronic files, images, multimedia, blog entries, and links. E-portfolios are both demonstrations of the user’s abilities and platforms for self-expression, and if they are online, they can be maintained dynamically over time. An e-portfolio can be seen as a type of learning record that provides actual evidence of achievement.

- Hybrid/Blended Course: The organization and presentation of course curriculum required to deliver a complete course that blends online and face-to-face teaching and learning activities.

- Illustration/Graphic: Visual concepts, models, and/or processes (that are not photographic images) that visually present concepts, models, and/or processes that enable students to learn skills or knowledge. These can be diagrams, illustrations, graphics, or infographics in any file format, including Photoshop, Illustrator, and other similar file types.

- Learning Object Repository: A searchable database of at least 100 online resources that is available on the Internet and whose search result displays an ordered hit list of items with a minimum of title metadata. A webpage with a list of links is not a learning object repository.

- Online Course: The organization and presentation of course curriculum required to deliver a complete course fully online.

- Online Course Module: A component or section of a course curriculum that can be presented fully online and independent from the complete course.

- Open Journal – Article: A journal or article in a journal that is free of cost from the end user and has a Creative Commons, public domain, or other acceptable use license agreement.

- Open Textbook: An online textbook offered by its author(s) with Creative Commons, public domain, or other acceptable use license agreement allowing use of the ebook at no additional cost.

- Photographic Image – Instructional: Photos or images of real people, places, or things that visually present concepts, processes, and/or phenomena that enable students to learn skills or knowledge. These can be photographs, images, or stock photography.

- Presentation: Teaching materials (text and multimedia) that are used to present curriculum and concepts to learners.

- Quiz/Test: Any assessment device intended to evaluate the knowledge and/or skills of learners.

- Reference Material: Material with no specific instructional objectives and similar to that found in the reference area of a library. Subject-specific directories to other sites, texts, or general information are examples.

- Simulation: Approximates a real or imaginary experience where users’ actions affect the outcomes of tasks they have to complete. Users determine and input initial conditions that generate output that is different from and changed by the initial conditions.

- Social Networking Tool: Websites and apps that allow users to communicate with others connected in a network of self-identified user groups for the purpose of sharing information, calls for actions, and reactions.

- Syllabus: A document or website that outlines the requirements and expectations for completing a course of study. Course Outlines would also be included in this.

- Tutorial: Users navigate through a set of scaffolded learning activities designed to meet stated learning objectives, structured to impart specific concepts or skills, and organized sequentially to integrate conceptual presentation, demonstration, practice and testing. Feedback on learner performance is an essential component of a tutorial.

- Video – Instructional: A recording of moving visual images that show real people, places and things that enable students to learn skills or knowledge.

- Workshop and Training Material: Materials best used in a workshop setting for the purpose of professional development.

- Other

Resources for Open Education Materials

By Don Watkins (Correspondent) August 23, 2016

Image by:Opensource.com

Shrinking school budgets and growing interest in open content has created an increased demand for open educational resources. According to the FCC, “The U.S. spends more than $7 billion per year on K-12 textbooks, but too many students are still using books that are 7-10 years old, with outdated material.” There is an alternative: openly licensed courseware. But where do you find this content and how can you share your own teaching and learning materials? This month I’ve rounded up a list of seven open educational resources for K-12 and higher education:

- OERCommons offers Open Author, which is platform agnostic and can be used to create media-rich documents simply by opening an account on the site. A lesson builder for K-12 content and a module builder

designed specifically for higher education are also available on the site. Follow OERCommons on Twitter:

@oercommons. - National Science Digital Library (NSDL) is a free site where teachers and students can share lesson plans. Joining the National Science Digital Library is easy—simply become a member of OERCommons,

a digital library and resource. Resources from preschool through adult education are available in 26 different resource types and 15 subject areas. Follow NSDL on Twitter: @nsdl - The CK-12 Foundationis a California-based nonprofit organization with a mission to reduce the cost of textbook materials for the K-12 market both in the U.S. and worldwide. Key benefits include: access to free textbooks; access to high-quality, educator-created content; support for publishing tools that make content creation easy; and licensing via Creative Commons CC BY-NC.CK-12 Foundation is providing us with the textbooks of the future, which are free, open, and remixable. Follow CK-12 on Twitter: @CK12Foundation.

- The Khan Academy site explains its mission as, “Khan Academy offers practice exercises, instructional videos, and a personalized learning dashboard that empower learners to study at their own pace in and outside of the classroom.” All material is openly licensed via the MIT Open License.

Follow Khan Academy on Twitter:@khanacademy. - The MIT Open Coursewaresite provides a web-based publication of virtually all of the 2,340 courses offered by Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Follow MIT OCW on Twitter: @MITOCW.

- Merlot is a curated collection of free and open online resources for teaching, learning, and professional development in higher education. Content is licensed under Creative Commons CC NC-ND (with some exceptions noted). Merlot offers a free content builder for registered site users. Follow Merlot on Twitter:

@MERLOTOrg. - Saylor Academy provides free online courses and an Open Course Option pathway to a free Associate in Science in Business Administration degree.

Follow them on Twitter:@saylordotorg. - What additions do you have for the list? Let me know about them in the comments.

Adapt or adopt the Content?

Adopt

Adopt means faculty will use the resource outright, with little or no changes to the content. This may be the way to go if they are truly happy with the resource or if they are just getting their feet wet. They can always try it out and make changes in later semesters if they want.

Adapt means they will be using the resource, but also adapting it. Perhaps they will add in an extra section of their own writing (to make it more relevant to their student demographic), or they will take out significant parts of an existing chapter. Either of these (and more) are excellent reasons to adapt a resource, rather than simply adopting it.

You indicated that the faculty did in fact find existing content. That is excellent news!

Now consider: Does your faculty member want to adopt or adapt the resource?

Adopt Content

Let’s make sure the students will be able to access it simply

Resource Format

First, what is the format of the resource in question? It might be a textbook offered in PDF, ePub, HTML, through Canvas Commons, or offered online in some other way.

If the resource is in Pressbooks, there is an LTI integration that places the content into direct view in Webcourses (so it appears just like a Webcourses Page would):

Insert an image of a Pressbook page.

If the person wants to use a resource external to Pressbooks, it’s usually pretty easy to point the students toward it. For instance, if a faculty member wanted to adopt this Engineering textbook offered through Open SUNY, they could simply link to that webpage and ask students to download the PDF from there.

The faculty member may want to download the PDF from the site and upload it into their course as well. If you’re really nifty like John Raible with this AMH2020 course, a big PDF could be broken into separate chapter PDFs and linked within each module. IDs aren’t expected to do this work, but you can point faculty to resources that might help them (e.g., https://oir.ucf.edu/fmc/).

Note: If the resource also comes in a print version, this will be helpful in the Communication Plan section below.

Communication Plan

Next is to discuss how to communicate with students about access to the resource. It’s recommended in the syllabus to clearly say that the resource is online and freely available. A direct link to the resource can be placed there.

If there is a print option, it should be mentioned in the syllabus (for instance, students could buy a print version of the Psychology OpenStax book if they really wanted to). In the case of print, list the ISBN number. When putting in an order to the bookstore, this ISBN can be listed but make sure that “come to class before buying book” is noted by the faculty member.

Here is the language used in the AMH2020 course which uses an OpenStax book: “U.S. History by OpenStax ISBN: 978-1-938168-36-9. The textbook is free and available online.

Textbook download instructions.

You can choose to print out the pages – free through Student Government – or if you insist, the book is for sale in the bookstore.”

Pro Tip: Encourage the faculty member to make their syllabus visible within PeopleSoft by using the Course Preview Feature before students register for the course, so students can see that the materials are free. Also consider sending out an email to the class roster before class starts so that students understand they don’t have to buy a copy.

LICENSE

Affordable Instructional Materials – ID Handbook. Copyright © 2019 by James Paradiso, Aimee deNoyelles, John Raible, Denise Lowe, Debra Luken is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Adapt Content

Below are some considerations to make when adapting open content:

- If your faculty have big ideas, ask them to consider adapting one chapter or section before doing the entire resource.

- Are your faculty going to create new content to add to an existing resource?

- Are your faculty going to try and find other OER to use in addition to this resource? What licenses do those resources have?

- The more restrictive the license, the more considerations will have to be given when adapting the content. (cf. Creative Commons licenses)

- Public Domain = You can do anything you’d like with the content.

- Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) = You can do anything, but have to attribute original work (like citing a paper).

- Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike = You can do anything, but have to release it under same CC license.

- Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial = You can modify, but can not sell it (i.e., print copies can not be sold by the bookstore).

- Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives = You can not modify; have to use as is. (Adapting is NOT an option here.)

- …or any mixture of the above.

- Make sure the appropriate licensing and attributions are applied to this new, adapted resource.

- Determine the format of these resources to plan appropriately for adapting them. (Some common file types are listed below.)

- HTML

- Word

- Images

- ePub

Adapting PDFs

PDFs are the most difficult file format to adapt. They can be either image-based or created from other products such as HTML or Microsoft Word.

- For the latter, you can copy the text and paste it into Word, Pressbooks, a plain text editor, et al.

- For image-based documents (i.e., you are unable to select the text), use

Adobe Acrobat Pro’s OCR (Optical Character Recognition) feature to turn the image into text. This process is not 100% effective depending on the quality of the image. OCR likes to switch b’s and d’s, and i’s for ! marks.

Adapting other file formats

With the exception of PDF documents, all other file formats (listed below) can be imported and modified directly in Pressbooks ( https://guide.pressbooks.com/chapter/tools/#importtool )or https://networkmanagerguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/getting-content-into-pressbooks/).

- Log in to Pressbooks to use the above functionality. (All users who accessed this book through Webcourses had a user account automatically created.)

The clearest advantage of using Pressbooks to edit and compile content is that the platform is internally supported by the Techrangers and UCF’s Pressbooks Network Manager (Jim), so any technical issues that arise or formatting issues you’d like to take care of can be managed through a TBD submission (or by contacting Jim directly).

Learn more about these ‘other’ file formats.

HTML

HTML provides the most flexibility in 1) styling via CSS, 2) including other artifacts (images, links, etc), 3) editing, 4) printing, and it’s the easiest to make accessible for users of assistive technology.

HTML files that can be linked and/or created in Webcourses@UCF, Webcourses@UCF Pages, or services like Pressbooks. HTML documents can also be easily transformed into accessible PDFs and be imported into an ePUB editor such as Sigil.

Word

Many of the advantages of HTML can be found in Word. The major drawback is the lack of customized styling available in HTML. For example, specialized layouts and customized line numbering. Accessibility resource for Word documents. Any Word document, however, can be easily imported and styled in Pressbooks (https://guide.pressbooks.com/chapter/import-from-word-docx/).

ePub

Another option is to create an ePub file. Think of it like a specially formatted zip file containing the materials and a table of contents. It is intended to be read on a tablet and sometimes on a laptop. Pressbooks and Sigil

are both great open-source ePub editors. Depending on your use case, you might choose one over the other.

LICENSE

Affordable Instructional Materials – ID Handbook Copyright © 2019 by James Paradiso, Aimee deNoyelles, John Raible, Denise Lowe, Debra Luken is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Finding, Evaluating, and Adapting Resources

Teachers have always created and shared teaching materials, though finding and reusing others’ work is not always simple. [1]

This chapter will teach you how to find free and openly licensed teaching resources that already exist and adapt them for use in your own classrooms.

Why It Matters

If you’re going to find the best open resources for your course, and share your work as OER, and join an OER community of practice, you need to know how to find, evaluate, and adapt openly licensed resources. And what if we want to think bigger, what effect might open education have globally?

How is the openness, the opportunity to revise, remix and share, of content potentially impactful on a global scale? If the public had access to and could creatively remix the world’s knowledge, what new opportunities might we find to address global challenges (e.g., United Nations Sustainable Development Goals)

Learning Outcomes

- Find OER in open repositories, Google, CC Search, and other platforms

- Evaluate how to reuse, revise, and remix the OER you find

- Demonstrate how different OER can be used together, paying attention to license compatibility.

Personal Reflection: What it Matters to You

Where do you currently find your learning resources? Do you seek open alternatives for materials you currently use? How do you evaluate your existing learning resources, and how can you apply those measures to openly licensed content? [2]

Once you identify the learning resources you currently use, ask yourself the following questions:

- Is this resource available to all of my learners at no cost?

- Can my learners and I keep a copy of this resource forever?

- Does my class have the legal rights to fix errors, update old or inaccurate content, improve the work, and share it with other educators around the world?

- Can my learners contribute to and improve our learning resources as part of their course work?

If the answer to these questions is “No,” you’re likely using learning resources that don’t provide the legal permissions you and your learners need to do what you want to do. Conversely, if you answered “Yes” to all of the questions, you are likely using OER.

Acquiring Essential Knowledge

Finding Resources

Not everything on the internet is OER, and some works labeled as “open” may not have the legal permissions to exercise the 5Rs. So how do you recognize OER and how do you choose which OER will work best in your class? Remember that for a resource to be an OER it has to be available to everyone at no cost and be in the public domain or under an open license.

Finding the resources you want to use is the first step to bringing OER into your classroom. Discovery is one of the primary barriers to educators using OER. Fortunately, there are many established ways to search for OER.

First, for a short introduction on how to find OER, watch this video: How can I find OER? https://www.youtube.com/embed/NJRIaQkiWKw?si=3VK3czyycj_jEy2D. If you want to know more about most popular general options for searching for OER, you might consider reading through this Open Washington course module.

OER Repositories and Search Tools

There are many websites that host large collections of OER (e.g., Wikimedia Commons), but some universities host their own OER repositories and services. A good first step is to do a general OER search using Google Advanced Search and filter your results by “Usage Rights” (pull-down menu at the bottom of the screen). See

Google’s post on how to use the tool effectively. There are also hundreds of online platforms on which you can share your openly licensed content. Creative Commons maintains a directory of some of the most popular OER platforms used by educators organized by content type (photos, video, audio, textbooks, courses, etc.), and here are a handful of largest, most often used OER search tools and repositories:

Try searching several different platforms and meta-search tools to find the greatest number of results to choose from.

Listservs and Google Groups

Open educators often ask each other for help when looking for OER on email listservs and Google Groups. Here are a few you might want to join:

- SPARC LibOER

- Community College Consortium for Open Educational Resources (CCCOER) Google Group

- Creative Commons Open Education Platform Mailing List

- Iowa OER Google Group

Openly Licensed Images

As you begin to use and create OER, remember that the images you use should be free and openly licensed, as well. Here are some sources you might consider for openly licensed images:

- Creative Commons CC Search

- Library of Congress Flickr Account

- The Met Collection

- Unsplash

- The Noun Project

- Nappy: Beautifully Diverse Stock Photos

Evaluating Sources

Just like any other teaching resources, you need to carefully evaluate the OER you plan on using in your teaching. Educators who are new to OER may have concerns about quality because OER are available for free and may have been remixed by other educators. The process of using and evaluating OER is not that different from evaluating traditional all-rights-reserved copyright resources. Whether education materials are openly licensed or closed, you are the best judge of quality because you know what your learners need and what your curriculum demands.

Subject specialists (educators and librarians) assess the quality and suitability of learning resources, often along the following criteria [3]:

|

Comprehensiveness |

Does it look like it covers the topic thoroughly and completely? |

|

Accuracy |

Do you notice any errors or inaccuracies? |

|

Relevance |

Does it fit your objectives? |

|

Longevity |

Will this resource remain relevant for a sufficient period of time? |

|

Clarity |

Will it be readable and easy to understand for your students? |

|

Consistency |

Does the OER have a unified style, perspective, and content? |

|

Modularity |

Can you easily change the order of chapters or sections, or delete sections entirely, and still have the work make sense? |

|

Organization/ Structure/ Flow |

Is the OER organized well into sections, headings, and chapters? Does the structure assist with accessibility? Does the content follow a logical progression? |

|

Interface |

How easy is the resource to use and navigate? |

|

Grammatical Errors |

Does the work seem like it was proofread? |

|

Cultural Relevance |

Who is this work speaking to? Who is it leaving out? |

And be careful not to let anyone tell you OER are “low quality” because they are free. As the SPARC OER Mythbusting Guide points out:

- In this increasingly digital and internet-connected world, the old adage of “you get what you pay for” is growing outdated. New models are developing across all aspects of society that dramatically reduce or eliminate costs to users, and this kind of innovation has spread to education resources.

- OER publishers have worked to ensure the quality of their resources. Many open textbooks are created within rigorous editorial and peer-review guidelines, and many OER repositories allow faculty to review (and see others’ reviews of) the material. There is also a growing body of evidence that demonstrates that OER can be both free of cost and high quality—and more importantly, support positive student learning outcomes.

Also, be careful not to get pulled into a debate about “high or low quality education resources,” when what educators should really be concerned about is “effectiveness.” Read these two posts from David Wiley: Stop Saying “High Quality” and No, Really – Stop Saying “High Quality.”

Remixing and Adapting Resources

Openly licensing learning materials enables educators to use the materials more effectively, which can lead to better learning and student outcomes. OER can be remixed and adapted, updated, tailored, and improved locally to fit the needs of learners by translating the OER into a local language, adapting a biology open textbook to align it with local science standards, or modifying an OER simulation to make it accessible for a student who cannot hear.

The ideas of remix and adaptation are fundamental to education. Creative reuse of materials created by other educators and authors is about more than just seeking inspiration; we copy, adapt, and combine different materials to craft education resources for our learners.

Photo by José Carlos Cortizo Pérez. CC BY 2.0

Incorporating materials created by others and combining materials from different sources can be tricky, not only from a pedagogical perspective, but also from a copyright perspective.

Online digital education resources have different legal permissions that empower (or not) the public to use, remix and share those resources. Here are a few of those legal categories:

- Public domain works (not restricted by copyright) can be remixed with any work. For example, anyone can remix the Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain with Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll.

- All-rights-reserved copyrighted works, available for free online, which you can only use under the project terms of service, or using an exception or limitation to copyright, such as fair use or fair dealing. For example, many MOOCs allow free reuse of their content, but do not allow copying, revise, remix, or redistribution.

- All-rights-reserved copyrighted works in closed formats do not allow the public to remix or adapt a work. For example, a blockbuster movie available only in streaming service that you cannot use or even link to.

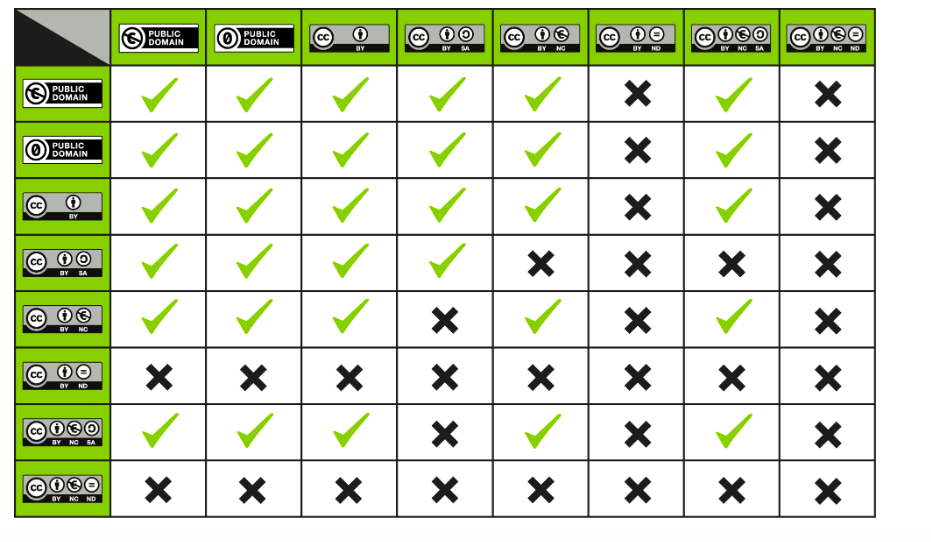

- Creative Commons licensed works (and other free licenses) that have various permissions and restrictions. For example, Wikipedia (BY-SA) allows you to reuse their content for commercial purposes, while WikiHow (BY-NC-SA) does not. A Wikipedia article cannot be remixed with a WikiHow article.

If you want to know which CC licensed works can be remixed with other CC licensed works, check out the

CC Remix Chart below. Where there is a green check at the intersection of two CC licensed works, you can remix those two works. Where you see a black X, you cannot remix those two CC licensed works.

CC License Compatibility Chart / CC BY 4.

Final Remarks

We live in a world of information abundance, and an increasing percentage of our digital knowledge is openly licensed. Finding the right open resources that fit the needs of your learning spaces and your learners can be a challenge. One of the major motivations for using OER is the ability to revise, remix, and share these works to best suit the needs of your learners. Search engines, OER repositories and platform services with built-in tools for using Creative Commons licenses help, but finding the right OER still takes time.

Attribution:

- The Creative Commons’ CC Certificate Resources , Chapter 5: Creative Commons For Educators, published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.↵

- This worksheet from University of Iowa’ OpenHawks program can help with evaluating the OER you find.

- Open Textbooks Review Criteria from the Open Textbook Network:

https://open.umn.edu/opentextbooks/reviews/rubric - Getting Started with Open Educational Resources by Mahrya Burnett, Jenay Solomon, Heather Healy is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.