3 Chapter 3: Assessment

- Assessment

- Questioning Techniques

- Feedback

Assessment

Even though you may think of instruction–the day-to-day activities of teaching–as the biggest part of your job as a future educator, assessment should actually come first. If you are following the backward design process, you should think first about your objectives and assessments and then about the activities that the students will do.

It is likely that when you think of assessment, you think of the grade you received at the end of an instructional unit. However, there are many kinds of assessment that serve different purposes. Table 3.1 outlines the differences among three key types of assessments: diagnostic, formative, and summative.

Table 3.1: Types of Assessments

|

Type |

Timing/Scoring |

Purpose |

Formats |

|

Diagnostic |

|

|

|

|

Formative |

|

|

|

|

Summative |

|

|

|

Assessment can also be formal or informal.

Formal assessments: measure systematically what students have learned, often at the end of a course or school year. Standardized tests are a common example of formal assessments. These high-stakes, formal assessments are designed to measure how well students have mastered the content listed in the standards. On the other hand, informal assessments tend to be local, non-standardized, and contextualized in daily classroom learning activities. Informal assessments are usually performance-based, meaning students are performing or demonstrating their understanding through a specific task. Teachers design assessments and may evaluate them with grades, rubrics, checklists, or other scoring conventions.

Formal Assessment: Measure systematically what students have learned, often at the end of a course or school year, such as with a standardized test.

Informal Assessments: these are local, non-standardized, and contextualized in daily classroom learning activities, often performance-based.

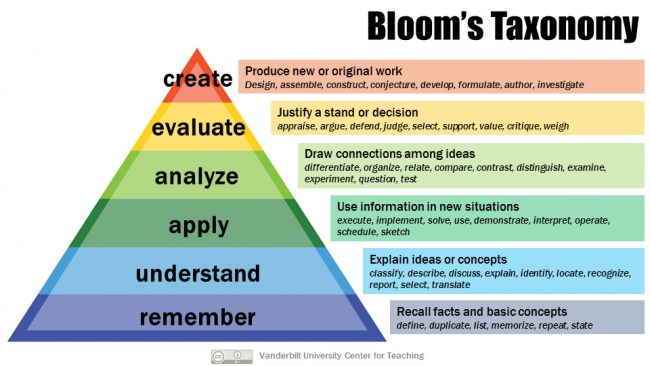

You will learn more about how to design high-quality assessments as you continue your journey toward becoming a teacher. For now, remember that high-quality assessments should always relate to the standards you taught in that particular lesson. This is called alignment. In addition, good assessments ask the right questions. For example, consider which of the following is more important as a life-long literacy skill: matching a secondary character in a text to a short phrase about what that person did or presenting a coherent argument that advances your position on a controversial topic? A useful tool for thinking about levels of questioning is Bloom’s Taxonomy (Figure 6.3). Bloom’s Taxonomy is a framework (Bloom et al., 1956) that divides levels of thinking into six categories, ranging from Knowledge to Evaluation. In response to some criticism, the taxonomy was later revised by a group of scholars, including Krathwohl (2002). The new version of the taxonomy included levels ranging from Remember to Create. It is important to understand that the framework is not meant to serve as a ladder that students must climb, where simpler knowledge and questions must always come first; rather, it is possible for students at all levels to consider information at all levels and move among them. This framework enables teachers to think about the kinds of questions they ask and vary them as needed. Less experienced teachers tend to rely more upon lower-level questions that require basic recall skills, so be intentional about asking questions that challenge students to venture into other levels of the taxonomy as well.

Figure 3.1: Bloom’s Taxonomy (Revised)

Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy gradually increases intellectual rigor of questions and learning tasks over six levels: remember, understand, apply, analyze, evaluate, and create. The original version was similar, with its six levels including knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation.

Designing and administering assessments that align with your standards and engage students at various levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy is an important first step, but another key part of effective assessments is analyzing the data you collect. Analysis of data can occur on individual student, small group, or whole class levels. If many students demonstrate a similar misunderstanding on an assessment, that data indicates the teacher should re-teach that content to increase students’ mastery. Data-driven instruction looks at the results of various assessments when considering next instructional steps. This analysis can be done by individual teachers or with colleagues in a PLC.

Reducing Bias in Grading by Using Rubrics

In an ideal world, grades and assessments are fair and impartial. However, the reality is that bias often creeps into assessment systems. One simple workaround is to use rubrics with specific criteria.

Quinn (2021) conducted an experiment in which he gave teachers two second-grade writing samples, one presented as a Black student’s work and one as a White student’s. Teachers gave the White student higher scores

except when they used a grading rubric with specific criteria, which caused the pre-existing racial bias in the scores to disappear. Therefore, rubrics not only help students know up front what expectations are for an assignment but also reduce opportunities for bias to impact grading.

Questioning Techniques

Introduction

The interaction between teacher and learners is the most important feature of the classroom. Whether helping learners to acquire basic skills or a better understanding to solve problems, or to engage in higher-order thinking such as evaluation, questions are crucial. Of course, questions may be asked by students as well as teachers: they are essential tools for both teaching and learning.

For teachers, questioning is a key skill that anyone can learn to use well. Similarly, ways of helping students develop their own ability to raise and formulate questions can also be learned. Raising questions and knowing the right question to ask is an important learning skill that students need to be taught.

Research into questioning has given some clear pointers as to what works. These can provide the basis for improving classroom practice. A very common problem identified by the research is that students are frequently not provided with enough ‘wait time’ to consider an answer; another is that teachers tend to ask too many of the same type of questions. (Adapted from Types Of Question, section Intro). (ORBIT)

Questioning Techniques

In 1940, Stephen Corey analyzed verbatim transcripts of classroom talk for one week across six different classes. His intent was to interrogate what the talk revealed about the learners’ increase in understanding. He wrote, however, that “the study was not successful for the simple reason that during the five class days involved the pupils did not talk enough to give any evidence of mental development; the teachers talked two-thirds of the time” (p. 746). The research focus thus shifted to patterns of questioning.

Findings included:

- For every student query, teachers asked approximately 11 questions

- Students averaged less than one question each, while teachers averaged more than 200 questions each

- Teachers often answered their own questions

- Fewer teacher questions require deep thinking by the learner

Much has changed since 1940 – except, it seems, these patterns. Classroom discourse continues to be dominated by the ‘recitation script’: teachers asking known-answer questions (Howe & Abedin, 2013) that limit opportunities for learners to experience cognitive challenges, thereby inhibiting effective learning (Alexander, 2008).

Effective questioning techniques are critical to learner engagement and are a key strategy for supporting students to engage thoughtfully and critically with more complex concepts and ideas.

Why Question?

The purpose of questioning

Teachers ask questions for a number of reasons, the most common of which are

- to interest, engage, and challenge students

- to check on prior knowledge and understanding

- to stimulate recall, mobilizing existing knowledge and experience in order to create new understanding and meaning

- to focus students’ thinking on key concepts and issues

- to help students to extend their thinking from the concrete and factual to the analytical and evaluative

- to lead students through a planned sequence which progressively establishes key understandings

- to promote reasoning, problem-solving, evaluation, and the formulation of hypotheses

- to promote students’ thinking about the way they have learned

The kind of question asked will depend on the reason for asking it. Questions are often referred to as ‘open’ or ‘closed’. Closed questions, which have one clear answer, are useful to check understanding during explanations and in recap sessions. If you want to check recall, then you are likely to ask a fairly closed question, for example, ‘What is the grid reference for Great Malvern?’ or ‘What do we call this type of text?’

On the other hand, if you want to help students develop higher-order thinking skills, you will need to ask more open questions that allow students to give a variety of acceptable responses. During class discussions and debriefings, it is useful to ask open questions, for example, ‘Which of these four sources were most useful in helping with this inquiry?’, ‘Given all the conflicting arguments, where would you build the new superstore?’, ‘What do you think might affect the size of the current in this circuit?’

Questioning is sometimes used to bring a student’s attention back to the task at hand, for example, ‘What do you think about that, Peter?’ or ‘Do you agree?’ (Adapted from Types Of Question, section Why).

Common Classroom Sequence

A striking insight provided by classroom research is that much talk between teachers and their students has the following pattern: a teacher’s question, a student’s response, and then an evaluative comment by the teacher. This is described as an Initiation-Response-Feedback exchange, or IRF. Here’s an example

I– Teacher – What’s the capital city of Argentina?

R – Pupil – Buenos Aires

F– Teacher – Yes, well done

This pattern was first pointed out in the 1970s by the British researchers Sinclair and Coulthard. Their original research was reported in Sinclair, J. and Coulthard, M. (1975) Towards an Analysis of Discourse: the English used by Teachers and Pupils. London: Oxford University Press.

Sinclair and Coulthard’s research has been the basis for extended debates about whether or not teachers should ask so many questions to which they already know the answer; and further debate about the range of uses and purposes of IRF in working classrooms. Despite all this, it seems that many teachers (even those who have qualified in recent decades) have not heard of it. Is this because their training did not include any examination of the structures of classroom talk – or because even if it did, the practical value of such an examination was not made clear?

A teacher’s professional development (and, indeed, the development of members of any profession) should involve the gaining of critical insights into professional practice – to learn to see behind the ordinary, the taken for granted, and to question the effectiveness of what is normally done. Recognizing the inherent structure of teacher-student talk is a valuable step in that direction. Student teachers need to see how they almost inevitably converge on other teachers’ styles and generate the conventional patterns of classroom talk.

By noting this, they can begin to consider what effects this has on student participation in class. There is nothing wrong with teachers’ use of IRFs, but question-and-answer routines can be used both productively and unproductively. (Adapted from The Importance of Speaking and Listening, section IRF). (ORBIT

Professor Robyn Gillies, from The University of Queensland, explores some questioning techniques and strategies that can support deep learning.

Example questions that promote dialogical discourse include things like:

- On the one hand, you’re telling me this, but on the other hand, you’re saying something quite different.

- I wonder how these two positions could be reconciled.

- Can you explain that another way?

- Tell us again what you meant by …?

- Have you considered looking at it this way? What might this or that type of person think about that?

These kinds of questions are designed to challenge students’ thinking and encourage them to think about things in different ways. By creating a state of cognitive dissonance in students, they have to reconsider their thinking.

Questions that scaffold students’ thinking might include things like:

- Have you considered using different descriptors in your search for the information you need?

- Have you thought about using some of this information to help you develop your ideas?

- Why don’t you try brainstorming some of the problems and how could you solve them?

Both types of questions are used interchangeably to help students clarify their thoughts and think more deeply about issues.

(UQx: LEARNx Deep Learning Through Transformative Pedagogy)

In this next video, Professor John Hattie, from the University of Melbourne, elaborates on our understanding of why questions are an essential component of developing self-regulated learners.

(4:43 minutes)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VFcO2SUj4jc

(UQx: LEARNx Deep Learning Through Transformative Pedagogy) https://youtu.be/VFcO2SUj4jc?si=_ydWAQRYG5AKJchA

Summary of research

Effective questioning

Research evidence suggests that effective teachers use a greater number of open questions than less effective teachers. The mix of open and closed questions will, of course, depend on what is being taught and the objectives of the lesson. However, teachers who ask no open questions in a lesson may be providing insufficient cognitive challenges for students.

Questioning is one of the most extensively researched areas of teaching and learning. This is because of its central importance in the teaching and learning process. The research falls into three broad categories

- What is effective questioning?

- How do questions engage students and promote responses?

- How do questions develop students’ cognitive abilities?

What is effective questioning?

Questioning is effective when it allows students to engage with the learning process by actively composing responses. Research (Borich 1996; Muijs and Reynolds 2001; Morgan and Saxton 1994; Wragg and Brown 2001) suggests that lessons where questioning is effective are likely to have the following characteristics:

- Questions are planned and closely linked to the objectives of the lesson.

- The learning of basic skills is enhanced by frequent questions following the exposition of new content that has been broken down into small steps. Each step should be followed by guided practice that provides opportunities for students to consolidate what they have learned and that allows teachers to check understanding.

- Closed questions are used to check factual understanding and recall.

- Open questions predominate.

- Sequences of questions are planned so that the cognitive level increases as the questions go on. This ensures that students are led to answer questions that demand increasingly higher-order thinking skills but are supported on the way by questions that require less sophisticated thinking skills.

- Students have opportunities to ask their own questions and seek their own answers. They are encouraged to provide feedback to each other.

- The classroom climate is one where students feel secure enough to take risks, be tentative, and make mistakes.

The research emphasizes the importance of using open, higher-level questions to develop students’ higher-order thinking skills.

Clearly, there needs to be a balance between open and closed questions, depending on the topic and objectives of the lesson. A closed question, such as ‘What is the next number in the sequence?’, can be extended by a follow-up question, such as ‘How did you work that out?’

Overall, the research shows that effective teachers use a greater number of higher-order questions and open questions than less effective teachers.

However, the research also demonstrates that most of the questions asked by both effective and less effective teachers are lower order and closed. It is estimated that 70–80 percent of all learning-focused questions require a simple factual response, whereas only 20–30 percent lead students to explain, clarify, expand, generalize, or infer. In other words, only a minority of questions demand that students use higher-order thinking skills.

How do questions engage students and promote responses?

It doesn’t matter how good and well-structured your questions are if your students do not respond. This can be a problem with shy students or older students who are not used to highly interactive teaching. It can also be a problem with students who are not very interested in school or engaged with learning. The research identifies a number of strategies that are helpful in encouraging student response. (See Borich 1996; Muijs and Reynolds 2001; Morgan and Saxton 1994; Wragg and Brown 2001; Rowe 1986; Black and Harrison 2001; Black et al. 2002.)

Pupil response is enhanced where

- there is a classroom climate in which students feel safe and know they will not be criticized or ridiculed if they give a wrong answer

- prompts are provided to give students the confidence to try an answer

- there is a ‘no-hands’ approach to answering, where you choose the respondent rather than have them volunteer

- ‘wait time’ is provided before an answer is required. The research suggests that 3 seconds is about right for most questions, with the proviso that more complex questions may need a longer wait time. Research shows that the average wait time in classrooms is about 1 second (Rowe 1986; Borich 1996)

How do questions develop students’ cognitive abilities?

Lower-level questions usually demand factual, descriptive answers that are relatively easy to give. Higher-level questions require more sophisticated thinking from students; they are more complex and more difficult to answer. Higher-level questions are central to students’ cognitive development, and research evidence suggests that students’ levels of achievement can be increased by regular access to higher-order thinking. (See Borich 1996; Muijs and Reynolds 2001; Morgan and Saxton 1994; Wragg and Brown 2001; Black and Harrison 2001.)

When you are planning higher-level questions, you will find it useful to use Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives (Bloom and Krathwohl 1956) to help structure questions that will require higher-level thinking. Bloom’s taxonomy is a classification of levels of intellectual behavior important in learning. The taxonomy classifies cognitive learning into six levels of complexity and abstraction.

Let’s look at Bloom’s Taxonomy presented earlier (Figure 3.1) in this chapter again.

On this scale, recalling relevant knowledge is the lowest-order thinking skill, and creating is the highest.

Bloom researched thousands of questions routinely asked by teachers and categorized them. His research, and that of others, suggests that most learning-focused questions asked in classrooms fall into the first two categories, with few questions falling into the other categories that relate to higher-order thinking skills.

Common Pitfalls of Questioning and possible solutions

Although questions are the most common form of interaction between teachers and students, it is fair to say that questions are not always well-judged or productive for learning. This section identifies some common pitfalls of questioning and suggests some ways to avoid them.

Not being clear about why you are asking the question: You will need to reflect on the kind of lesson you are planning. Is it one where you are mainly focusing on facts, rules, and sequences of actions? If that is the case, you will be more likely to ask closed questions which relate to knowledge. Or is it a lesson where you are focusing mainly on comprehension, concepts, and abstractions? In that case, you will be more likely to use open questions that relate to analysis, synthesis, and evaluation.

Asking too many closed questions that need only a short answer: It helps if you plan open questions in advance. Another strategy is to establish an optimum length of response by saying something like, ‘I don’t want an answer of less than 15 words.’

Asking too many questions at once: Asking about a complex issue can often lead to complex questions. Since these questions are oral rather than written, students may find it difficult to understand what is required, and they become confused. When you are dealing with a complex subject, you need to tease out the issues for yourself first and focus each question on one idea only. It also helps to use direct, concrete language and as few words as possible.

Asking difficult questions without building up to them: This happens when there isn’t a planned sequence of questions of increasing difficulty. Sequencing questions are necessary to help students to move to the higher levels of thinking.

Asking superficial questions: It is possible to ask lots of questions but not get to the center of the issue. You can avoid this problem by planning probing questions in advance. They can often be built in as follow-up questions to extend an answer.

Asking a question then answering it yourself: What’s the point? This pitfall is often linked to another problem: not giving students time to think before they answer. Build in ‘wait time’ to give students a chance to respond. You could say, ‘Think about your answer for 3 seconds, then I will ask.’ You could also provide prompts to help.

Asking bogus ‘guess what’s in my head’ questions: Sometimes teachers ask an open question but expect a closed response. If you have a very clear idea of the response you want, it is probably better to tell students by explaining it to them rather than trying to get there through this kind of questioning. Remember, if you ask open questions, you must expect to get a range of answers. Acknowledge all responses. This can easily be done by saying ‘thank you’.

Focusing on a small number of students and not involving the whole class: One way of avoiding this is to get the whole class to write their answers to closed questions and then show them to you together. Some teachers use small whiteboards for this. Another possibility, which may be more effective for more open questions, is to use the ‘no-hands’ strategy, where you pick the respondent rather than having them volunteer. One advantage of this is that you can ask students questions of appropriate levels of difficulty. This is a good way of differentiating to ensure inclusion.

Dealing ineffectively with wrong answers or misconceptions: Teachers sometimes worry that they risk damaging students’ self-esteem by correcting them. There are ways of handling this positively, such as providing prompts and scaffolds to help students correct their mistakes. It is important that you correct errors sensitively or, better still, get other students to correct them.

Not treating students’ answers seriously: Sometimes, teachers simply ignore answers that are a bit off-beam. They can also fail to see the implications of these answers and miss opportunities to build on them. You could ask students why they have given that answer or if there is anything they would like to add. You could also ask other students to extend the answer. It is important not to cut students off and move on too quickly if they have given a wrong answer.

Practical tips

- Be clear about why you are asking the questions. Make sure they will do what you want them to do.

- Plan sequences of questions that make increasingly challenging cognitive demands on students.

- Give students time to answer and provide prompts to help them if necessary. Ask conscripts rather than volunteers to answer questions

Reflection

- Look again at the list of pitfalls and think about your own teaching. Which of these traps have you fallen into during recent lessons?

- How might you have avoided them?

Additional Resources

100 questions that promote Mathematical Discourse-Download Printable Version for quick reference

References

ORBIT: The Open Resource Bank for Interactive Teaching, University of Cambridge, Faculty of Education. Retrieved from http://oer.educ.cam.ac.uk/wiki/Questioning_Research_Summary and http://oer.educ.cam.ac.uk/wiki/Teaching_Approaches/Questioning (CC BY NC SA)

LEARNx Deep Learning through Transformative Pedagogy (2017). University of Queensland, Australia (CC BY NC SA)

LICENSE

Instructional Methods, Strategies and Technologies to Meet the Needs of All Learners Copyright © 2017 by Faculty of Education and UQx LEARNx team of contributors;

The Open Resource Bank for Interactive Teaching; and University of Cambridge is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Feedback

Professor Merrilyn Goos from The University of Queensland defines what we mean by ‘feedback for deep learning.’

Feedback is something that tells you if you’re on the right track or not. In a nutshell, feedback is information provided on the performance or understanding of a task, which can then be used to improve this performance or understanding. Feedback helps to close the gap between actual performance and intended performance. There are a multitude of different types of feedback and we encounter many of these in our everyday lives.

Feedback can come from a diverse variety of sources as well. Feedback doesn’t need to be formal. In fact, some feedback is very informal, and we hardly recognize it for what it is. Feedback has a powerful influence on learning and, in particular, on deep engagement with content. If we would like our students to have a full understanding of a task and gain skills they can use in the future and transfer to other tasks, then effective feedback on learning is crucial.

For a fuller understanding of the nature of feedback and how it can be used to close the gap between actual performance and intended performance, we need to explore the different purposes, types, and levels of feedback and ask three important questions:

1) Where am I going?

2) How am I going? and

3) Where to next?

(Hattie & Timperley, 2007).

In exploring the Hattie and Timperley (2007) feedback model and the three feedback questions, van den Bergh, Ros, and Beijaard (2012, p. 345) state: The first question is about the learning goals: ‘Where am I going?’

The second question that has to be answered is: ‘How am I going?’ Learners need to know how the current performance relates to the learning goals.

Finally, learners will ask: ‘Where to next?’ What activities need to be undertaken to make better progress?

Conditions of Effective Feedback

Dr Cameron Brooks from the School of Education at The University of Queensland, Australia, explored the conditions that are important for effective feedback and how powerful effective feedback can be for deep learning.

“Effective feedback is essential for deep learning. However, what is often overlooked is the potential for feedback to have variable effects on learning

” (Brooks, 2021).

The use of feedback is regarded as one of the most powerful strategies to improve student achievement, and you may or may not be aware of just how much attention it receives in education policy and practice. As we explore effective feedback, I want you to reflect on ways feedback has influenced you in your own learning journey.

Feedback is typically viewed as information given to the student which is designed to cause modifications of actions and result in learning.

Recently, this cause-and-effect notion of feedback has been challenged as the provision of feedback is no guarantee of learning. Research suggests that much of the feedback that is given is, in fact, rarely used by students. For this reason, we need to focus on how feedback is being received rather than just how feedback is given. The effects of feedback on learning have been studied by educational and psychological researchers since the early 20th century.

Feedback is typically related to greater academic achievement, improvements in student work, and enhanced student motivation. Further investigation of feedback research, however, reveals that feedback produces highly variable effects on learning. Numerous variables are identified in feedback literature that affect how feedback is received and used by students. These include the purpose, focus, and timing of feedback.

Feedback can serve many different purposes, such as providing a grade, a justification of a grade, a qualitative description of the work, praise, encouragement, identification of errors, suggestions on how to fix errors, and guidance on how to improve the work standard.

- Feedback can be directive and tell students where they went wrong or facilitative and provide guidance on how to improve.

- Feedback that includes elaborations about how to improve is more likely to lead to improvements in learning efficiency and student achievement.

- Improvement-based feedback that includes guidance is more effective than statements about whether work is right or wrong as it takes into consideration how learners receive feedback.

Literature on student perceptions of feedback includes findings that students become frustrated with feedback that is too general or tells them where they went wrong but does not provide guidance on how to improve. Effective feedback tells students how they are doing in relation to goals and criteria and then provides guidance and opportunities for improvement.

Unfortunately, much of the feedback that is given in classrooms is directed to the self rather than to these specific learning elements of tasks. Research directed to the self, most commonly given as praise, has been found to have negative impacts on learning as it can contribute towards learners developing a mindset that sees achievement as a fixed attribute rather than something to be worked on and improved.

Early behavioristic feedback models used feedback as a means of reinforcement of behavior with the belief that feedback needs to be immediate to help condition a response. As cognitivist theories emerged, researchers began to investigate the effects of immediate versus delayed feedback upon learning.

Immediate feedback vs. delayed feedback

Immediate feedback is more likely to be effective in the acquisition of verbal, procedural, and motor skills. While immediate feedback is helpful during initial task acquisition, it can negate deeper learning during tasks that encourage fluency and the development of skills and understanding.

In fact, delayed feedback can be more effective for difficult tasks due to the benefits associated with learners’ processing and thinking about methods to satisfy task requirements. Therefore, delayed feedback may be beneficial for deeper learning, where learning concepts can be transferred from one context to another. This is, of course, dependent upon the type of task and the developmental capability of the learner.

Four common key conditions for effective feedback are evident from research:

- Clarifying expectations and standards for the learner,

- Scheduling ongoing, targeted feedback within the learning period,

- Fostering practices to develop self-assessment, and

- Providing feed-forward opportunities to close the feedback loop.

Let’s have a look at each of these conditions in more detail.

Clarifying expectations and standards for the learner.

Clarifying expectations and standards for the learner is a key prerequisite for effective feedback practice. The clarification of criteria and standards at the beginning of, or at least during the learning cycle, orients learners towards purposeful actions designed to satisfy or even exceed the learning intent or goals.

Feedback pertaining to expectations and standards that arrive at the conclusion of the learning cycle is terminal and of limited value, primarily due to the learner not being given further opportunity to be able to implement the feedback. Feedback has the potential to be increasingly powerful when the task intent and the criteria for success can be matched to challenging learning goals.

Goals are a powerful strategy for focusing the intention of learners on the feedback standard gap, for instance, the difference between where the learner currently is in the learning cycle and where they need to be at the end of the learning journey. Teachers need to be clear and specific when providing guidance on expectations, as students hold different interpretations of the learning intent from their instructors.

An example of an effective strategy for clarifying expectations and standards is the use of exemplars or models. Exemplars are particularly effective as they clearly depict the required standards and enable students to make a direct comparison between their own work and the stated standards of the exemplar. Students also report they value feedback that is matched to the assessment criteria.

Crucially, feedback pertaining to the clarification of the expectations and standards lays the platform for students to monitor their own learning progress, and this is a key facet of self-regulated learning.

Scheduling ongoing, targeted feedback within the learning period.

Ongoing, targeted, and specific feedback received within the current learning period is more powerful than feedback received after learning.

Hence, formative rather than summative assessment is a key process for creating opportunities for feedback. Formative assessment provides learners with opportunities to both receive and implement feedback with a view to improving their work. The scheduling of formative assessment checkpoints throughout the learning period gives students multiple opportunities to demonstrate their knowledge, understanding, and skills.

Formative assessment also provides teachers with an evidence base of how their students are tracking towards achieving the learning intent. By comparing the learning intent and criteria for success with the student’s current learning state (as evidenced within their formative assessment samples), teachers can direct their attention to the gap between where the learner is currently situated and where they need to be. Teachers can then draw upon pedagogical practices such as differentiation and scaffolding to meet the individual needs of learners before the conclusion of the learning period.

Fostering practices to develop self-assessment

Self-regulation is a key process within an effective model of feedback for deep learning. Self-regulated learners are cognizant of both the standards and criteria and their own current levels of performance or achievement. To develop self-regulatory behaviors, learners must be regularly engaged in tasks and activities that match the criteria for success and include processes, such as self-assessment, that encourage critical thinking and reflection.

Calibration mechanisms such as self-review, retrieval questions, peer feedback, comparison with models, and exemplars all allow students to compare their work against given standards and, importantly, identify areas for improvement.

Self-assessment thus forms part of self-regulation, where students can direct and monitor actions to achieve the learning intent. Students who develop self-regulatory learning habits become willing and active seekers of feedback.

Feed-forward opportunities to close the feedback loop.

The final condition for effective feedback is the provision of opportunities for students to implement the feedback and close the feedback loop. The closing of the feedback loop is crucial as it requires learners to act on earlier feedback that they have received or self-generated. Often termed feed-forward, this highly valued process is often missing from some learning episodes due to delays in students receiving the feedback or misinterpretation of the feedback content.

Thus, feed-forward is heavily reliant on the three conditions of effective feedback that were discussed previously. When further consideration is given to incrementally increasing task challenges, feed-forward opportunities can foster great improvement in learners.

In conclusion, variables such as the purpose, focus, and timing of feedback can cause learners to receive feedback differently. Teachers need to strive to provide conditions for learners where feedback is more likely to be effective. These conditions include the clarification of expectations, the use of ongoing formative assessment, feedback that is aimed at developing self-regulation, and the provision of feed-forward opportunities.

In the video below, Dr. Cameron Brooks from the University of Queensland provides effective feedback coaching for teachers in Brisbane, Australia. Watch Cameron work with teachers and think about the types of feedback teachers receive.

Watch the Video: (8:02 minutes)

In this next video, Dr. Cameron Brooks from the University of Queensland talks about the model he developed for effective feedback.

Click here to watch the video (8:41 minutes)

Click here to view and download the Feedback Matrix

Peer Feedback

Ultimately, learners need to be their own self-assessors in order to engage deeply with new content, processes, and skills. Peer- and self-feedback play very important roles in developing the type of self-initiated feedback for essential deep learning.

Dr. Melissa Cain from The University of Queensland explores the many advantages of providing and receiving peer feedback

MELISSA CAIN: Have you ever been asked to provide feedback to a friend or colleague? Did you find that easy? What concerns did you have? Were you worried that your feedback wouldn’t be welcomed or that it might not be helpful?

Alternative assessment methods, such as peer assessment, are growing in popularity and have been found to receive a more positive response from students than more traditional assessment approaches. Engaging in peer feedback as part of the formative assessment process develops a range of critical thinking skills and is important in developing deep learning competencies.

Stephen Bostock, Head of the Centre for Learning, Teaching and Assessment at Glyndwr University relates

that there are many benefits in providing and receiving peer feedback. Engaging in peer feedback gives students a sense of belonging and encourages a sense of ownership in the process.

This type of engagement also helps students recognize assessment criteria and develops a wide range of transferable skills. Interacting with their peers in this manner provides learners with opportunities to problem-solve and reflect. It increases a sense of responsibility, promotes independent learning, and encourages them to be open to a variety of perspectives. Commenting on the work of peers enables learners to engage with assessment criteria, thus inducting them into assessment practices and tacit knowledge. Learners are then able to develop an understanding of standards that they can potentially transfer to their own work.

Challenges of peer assessment

There are, however, some challenges surrounding the provision of effective peer feedback. Ryan Daniel, professor of creative arts at James Cook University, suggests that there exists the potential for resistance to peer feedback as it appears to challenge the authority of teachers as experts.

Indeed, students themselves have strong views about the effectiveness of peer assessment methods. This includes an awareness of their own deficiencies in subject areas, not being sure of their own objectivity, the influence of interpersonal factors such as friendship, and the belief that it is not their job but the teachers’ to provide feedback.

Learners may also be cautious of being criticized by their peers and worry about a lack of confidence in their ability to provide effective feedback. Part of this issue relates to the issue of teacher power in the classroom. As this power is usually considered absolute by students, they may, in fact, consider their role to please teachers rather than demonstrate their learning by providing feedback. Providing effective peer feedback cannot be a one-time event. Learners need to be prepared over time to provide effective feedback.

Spiller (2011) suggested that learners need to be coached using examples and models and should be involved in establishing their own assessment criteria if possible. Teachers should demonstrate how they can match the work of a learner to an exemplar that most closely resembles its qualities. And everyone should engage in rich discussions about the process following the provision of peer feedback. As students become better at providing peer feedback over time, they gain confidence and become more competent at it.

Learning to provide peer feedback has many advantages. Most importantly, when students evaluate their peers’ work and provide timely, specific, and personalized feedback, they have the opportunity to scrutinize their own work as well. This is a critical factor in deep learning.

Peer Critique: Creating a Culture of Revision

Your students can improve their work by recognizing the strengths and weaknesses in the work of others.

Watch the video: Be Kind, Be Specific, Be Helpful: (4:32 minutes)

Using Self and Peer Feedback as Assessments for Learning

Watch the video: Using Self and Peer Feedback as Assessments for Learning (2:44 minutes)on using self and peer feedback as assessments for learning. (2:44 minutes)

References

- [Edutopia]. (Nov. 1, 2016). Peer Critique: Creating a Culture of Revision. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M8FKJPpvreY

- [PERTS]. (Jan. 6, 2016). Using Self and Peer Feedback as Assessments for Learning. [Video File] Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6Ckrbsigh9E

- UQx: LEARNx Deep Learning through Transformative Pedagogy (2017). University of Queensland, Australia (CC BY NC)

Attribution:

- Instructional Methods, Strategies and Technologies to Meet the Needs of All Learners by UQx LEARNx team of contributors is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.