Chapter 9-: Micro Teaching

- What is Microteaching

- Peer Assessment in Microteaching

- Benefits of Engaging in Peer Review of Teaching

What is microteaching?

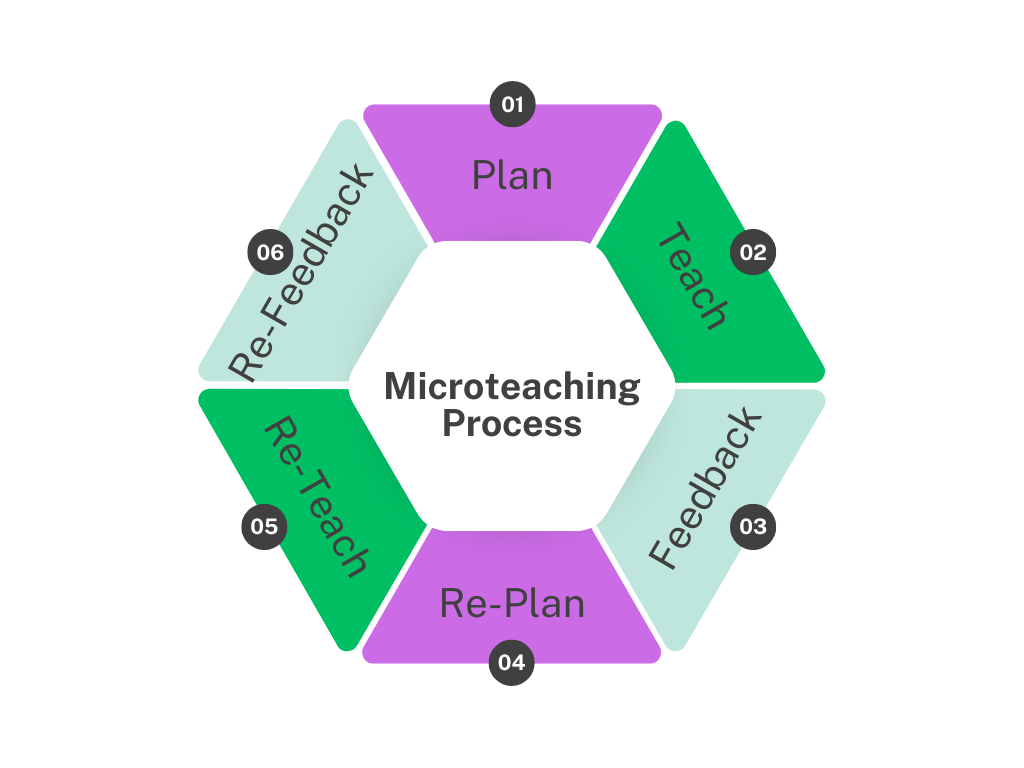

Why wait for student evaluations to receive feedback on teaching practices? Microteaching provides an opportunity for faculty and instructors to improve their teaching practices through a “teach, critique, re-teach” model. Microteaching is valuable for both new and experienced faculty to hone their teaching practices. It is often used in pre-service teacher training programs to provide additional experience before or during the clinical experiences.

Microteaching is a concentrated, focused form of peer feedback and discussion that can improve teaching strategies. It was developed in the early and mid-1960s by Dwight Allen and his colleagues at the Stanford Teacher Education Program (Politzer, 1969) The microteaching program was designed to prepare the students for their internships in the fall. In this early version of microteaching, pre-service teachers at Stanford taught part-time to a small group of pupils (usually 4 to 5). The pupils were high school students who were paid volunteers and represented a cross-section of the types of students the pre-service teachers would face during their internships.

Why use microteaching?

Microteaching has several benefits. First, because the lessons are so short (usually 5 to 10 minutes), they have to focus on specific strategies. This means that someone participating in a microteaching session can get feedback on specific techniques he or she is struggling with. In a pre-service or training situation, participants can practice a newly learned technique in isolation, rather than working that technique into an entire lesson (Vare, 1993).

Microteaching is also an opportunity to experiment with new teaching techniques. Rather than trying something new with a real class, microteaching can be a laboratory to experiment and receive feedback, first (Kuhn, 1968).

How does micro-teaching work?

In the classic Stanford model, each participant teaches a short lesson, generally 5 to 10 minutes, to a small group. The “students” may be actual students, like in the original Stanford program, or they may be peers playing the role of students. In the case of pre-service teachers and teaching assistants, there generally is at least one “expert”, as well. If desired, the session can be videotaped for review later (Vare, 1993).

The presentation is followed by a feedback session. In some cases, the feedback session can be followed by a re-teach, so that the instructor has an opportunity to practice the improvements suggested during feedback (Vare, 1993).

Giving Feedback

Receiving criticism is hard for all of us. Setting a tone of respect and professionalism may help participants to be tactful and to keep feedback constructive. Here is an example of ground rules used by the CASTL program at California State University (http://fdc.fullerton.edu/learning/CASTL/carnegie_microteaching_materials.htm):

Ground Rules

- Respect confidentiality concerning what we learn about each other.

- Respect agreed-upon time limits. This may be hard, but please understand that it is necessary.

- Maintain collegiality. We’re all in this together.

- Stay psychologically and physically present and on task.

- Respect others’ attempts to experiment and to take risks.

- Listen and speak in turn, so everyone can hear all comments.

- Enjoy and learn from the process!

Feedback should be constructive and based on observation, rather than judgments. A good example of feedback is “You fidget with your pen while talking, and that is distracting,” rather than “You seem nervous and unprepared.” The first comment is about observable behavior, while the second is a judgment about what that behavior means.

Commenting on observable behavior also leads to suggestions for improvement. Again, using our pen example, a better example of feedback would be, “You fidget with your pen while talking. Perhaps it would be better to keep a hand in your pocket.”

In the Stanford model, feedback was given using a 2+2 system. Each participant started their feedback with two positive comments, followed by two suggestions for improvement. This gives the instructor a sense of his or her strengths and areas of improvement.

How can microteaching be used?

The most common application for microteaching is in pre-service teacher training, like the original Stanford model. However, that certainly isn’t the only application. Microteaching has also been used to train teaching assistants and new faculty on teaching methods. Even experienced faculty can refine their teaching techniques using microteaching.

A similar technique, micro-rehearsal, has been used to train prospective music conductors. (Kuhn, 1968) Like microteaching, the students conduct a 5- to 10-minute rehearsal with sample musicians. Following the rehearsal, the musicians provide feedback on the prospective conductor’s rehearsal technique.

Microteaching techniques can also be used in other fields. In business, microteaching can be used to focus on presentation skills, persuasion and negotiation techniques, and interviewing techniques. In counseling and social work, microteaching can be used to hone questioning and active listening skills. It also applies outside of the classroom. For example, departments like Career Service can use

microteaching techniques to prepare students for job interviews.

Ultimately, microteaching is a useful technique for teaching soft skills, presentation skills, and interpersonal skills. This focused approach encourages growth through practice and critique. The “teach, critique, re-teach” model gives the instructor immediate feedback and increases retention by providing an opportunity for practice.

References

- Kuhn, W. (1968). Holding a Monitor up to Life: Microteaching. Music Educators Journal, 55(4), 49-53.

- Politzer, R. (1969). Microteaching: A New Approach to Teacher Training and Research.

Hispania,52(2), 244-248. - Vare, J. W. (1993). Co-Constructing the Zone: A Neo-Vygotskian View of Microteaching.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

https://oercommons.s3.amazonaws.com/media/courseware/relatedresource/file/Micro_Teaching_ussdbNX.pdf

Peer Assessment in Microteaching

Overview

Peer Assessment in microteaching is an interactive evaluation technique where peers review and critique each other’s teaching presentations in a microteaching session.

Microteaching is an innovative practice-oriented approach where teaching sessions are conducted on a smaller scale, often with a reduced duration and with a few students or peers acting as learners. This method facilitates a supportive environment where aspiring teachers can experiment with new teaching strategies, receive immediate constructive feedback, and engage in reflective practice. During these sessions, participants take turns teaching short lessons on chosen topics, after which they receive feedback from their peers based on specific assessment criteria such as lesson plan, delivery, clarity of instruction, interaction/ engagement strategies, content knowledge, uses of visual aid and/or technology integration, peer feedback and responsiveness to learner needs. Additionally, microteaching involves a cycle of steps of how to plan, the way of teaching, observation, assessing learning, replanning, reteaching, and reobserving. In general,microteaching is a useful tool for assisting novice teachers in learning about and reflecting upon good teaching methods and can be best assessed by peers.

Objective

The primary aim of Peer Assessment in Microteaching: This assessment method was designed to assess and improve teaching skills, pedagogical approaches, and classroom management strategies. By participating in peer assessment, educators are encouraged to critically evaluate their own teaching practices and those of their colleagues, promoting a culture of continuous learning and improvement. The process is intended to help i) educators become more adaptable, responsive, and effective in their teaching methods, ultimately enhancing student learning outcomes. ii) to promote a reflective teaching practice, and iii) to build a collaborative professional community where prospective teachers and educators can share best practices, challenges, and innovations in teaching.

Grading

The rubric consists of key aspects of teaching effectiveness and peer feedback. The aspects of teaching include:

- Lesson Planning: whether the Lesson is well-structured, objectives are clear, and materials are effectively utilized.

- Lesson delivery: whether the teaching/class presentation considered student-centered approaches, engaging, clear, and well-paced, with excellent use/choice of language.

- Observation on Patterns of Interactions: whether the lesson has demonstrated an exceptional ability to engage students, encourages participation, and responds effectively to questions, and effectively uses technology for interactive learning.

- Uses of visual aid and technology integration/with technology enhanced activities: whether innovative methods of teaching aids were used, and technology integrated that may significantly enhance learning outcomes.

- Classroom management: whether there is evidence of exceptional ability to manage classroom dynamics, disruptive

behaviors, and maintaining an effective and inclusive learning environment. - Language skills: skillfully integrated and balances all four language skills (listening, speaking, reading, and writing) and subskills (grammar, vocabulary, pronunciation, etc. ), promoting comprehensive language development.

- Pragmatism and Cultural awareness: Lessons reflect the practical application of concepts, encouraging real-world understanding and engagement. Incorporates real-world applications and cultural contexts into their lessons. These elements are crucial for creating engaging, relevant, and inclusive learning environments.

- Inclusivity: demonstrates outstanding ability to adapt lessons for adult learners who do not speak Kiswahili as a second/foreign language. Also, focus on students with special learning needs, ensuring accessibility and engagement.

- Quality Peer Feedback: Provides constructive, specific, and respectful feedback that contributes to professional growth, and provides actionable feedback, including perspectives on inclusivity, and differentiation for diverse learners.

Assessment criteria

From Excellent- Good – Satisfactory – Need Improvement Scoring points: Total points earned across all criteria determined the peer assessment grade. The maximum score was 20 marks. Feedback was detailed, highlighting strengths and areas for improvement.

Role of Peer Assessment in Microteaching

Implementing peer assessment in microteaching fostered a collaborative learning environment where peers could openly share feedback, insights, and teaching strategies. This method significantly enhanced reflective practice, as participants could see their teaching through the eyes of their peers, leading to a deeper understanding of their pedagogical strengths and areas for improvement.

Peer Evaluation: Your Feedback is Critical Role You Play

One challenge noted was the variability in the quality and depth of feedback provided by peers, and culturally, peers were uncomfortable offering feedback to their peers. The cultural discomfort associated with offering peer feedback, highlights the crucial areas for consideration in implementing peer assessments. Consider the importance of constructive criticism in professional growth. Consider when providing feedback:

- Follow the TAG! approach (Tell something good, Ask questions, Give suggestion, and anything you like to add)

- Should be constructive

- Should be consistent and depth across all evaluations

- The importance of specific, actionable feedback to enhance teaching practices.

Remember, the peer assessment process is a learning opportunity not just for the presenters who do the microteaching but also for the the evaluators as well because analyzing and assessing teaching practices can deepen one’s own understanding and approach to teaching.

Video: 60-Second Strategy: TAG Feedback

Source: https://youtu.be/OdYev6MXTOA?si=Es7WLURrpGnclP1Z

Attribution:

- Handbook of Alternative Assessments. Copyright © by Dr Maryam Jaffar Ismail is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise note

Benefits of Engaging in Peer Review of Teaching

- Gain a sense of community: Teacher candidates may often feel as if they will be teaching and dealing with the challenges of this work in isolation. Soliciting and receiving feedback from your peers can help to break down silos and create community by sharing things that have worked well and lessons learned with your colleagues (Hutchings, 1996).

- Receive feedback from multiple perspectives: It is important to consider collecting feedback from different perspectives (peers, instructor, university supervisor, instructors, or students) to ensure that all the feedback you are collecting reveals a similar story and outcome. Hence, peer feedback will allow you to collect information, re-plan your lesson as needed, and re-teach it to improve your teaching to help you grow profession

ally.

- Observing your peers can also help enhance your teaching:

If you take on the role of a peer reviewer, observing a colleague’s teaching techniques can spark new ideas for your own teaching. You should meet regularly to discuss your observations – not to provide evaluative feedback but to gather ideas that you both might want to implement in your own courses.

Leverage peer feedback to improve your teaching:

Peer review can help to increase critical reflection of teaching and can motivate and encourage you to experiment with new teaching methods. Research has shown that instructors who participate in peer review incorporate more active learning strategies in their courses, increase the quality of their feedback to students, and report enjoying discussing teaching with their colleagues (Bernstein, 2000).

Attribution:

- Peer Feedback on Your Teaching.”by Crystal Tse, Center for the Advancement of Teaching Excellence at the University of Illinois Chicago. This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International.For more information about Peer Feedback on Teaching, Access: University of Illinois- Chicago