Healthcare Reform

Introduction

Business has become a powerful force in medicine. The future of health care cannot escape that reality. “The US recently experienced the most devastating recession since the Great Depression” (Wicks & Keevil, 2021) and a global crisis with the COVID-19 epidemic. As healthcare costs rise, the pressure to rein in healthcare spending is ever-present. New legislation could make a significant shift in how healthcare is provided and who has access to care.

In 2010, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was the largest piece of legislation to pass regarding healthcare in America. It aimed to reduce healthcare costs by providing affordable insurance to the underinsured and uninsured. It encompassed individuals making between 100% and 400% above the national poverty level. However, it was not embraced by states equally. More conservative states in the southern regions did not adopt Medicaid Expansion and did little to ensure the ACA’s success. The array of issues facing the US healthcare system urges the need for new health reform to address rising costs, reduce medical errors, strengthen patient rights, build public health infrastructure, and confront the costs of medical malpractice insurance. Pollard (2022) provides several factors that deter significant social/health reform in this country, including:

- Political gridlock: The US political system is highly polarized, with two major parties that often have very different views on social and health policy. This makes it difficult to pass major reforms that require bipartisan support.

- The influence of special interests: Powerful special interests, such as the healthcare industry, often oppose reforms that would threaten their profits. They can use their financial resources and political influence to block or weaken reform efforts.

- Public apathy: Many Americans are not well-informed about social and health policy issues, and they may not see reform as a priority. This can make it difficult to build public support for reform efforts.

- The complexity of the issue: Social and health policy issues are often complex and difficult to understand. This can make it difficult to reach a consensus on the best course of action.

- The cost of reform: Social and health reform can be expensive, and there is often disagreement about who should pay for it. This can be a major obstacle to reform efforts.

Learning Objectives

- Summarize the implications of reform for health professionals, such as physicians, nurses, or pharmacists

- Describe the increased complexity of relationships between physicians, healthcare institutions, and drug and device manufacturers

- Articulate how healthcare is different from other industries based on policies and regulations

- Determine how to find an acceptable equilibrium between market and professional service paradigms for healthcare

Business

Clarifying the Definition of Business

Business, in terms of healthcare, is about being an employer who offers opportunities that are more attractive than others, provides a chance to develop the employee’s abilities, and does work that has value. Businesses should start with a realistic view of what they do, particularly if the right kinds of conditions are present. Business is defined in two ways:

- The practice of making one’s living by selling a product or service; or

- An organization engaged in commercial, industrial, or professional activities.

Businesses can be for-profit entities or non-profit organizations. Business types range from limited liability companies to sole proprietorships, corporations, and partnerships.

Measuring Impact and Performance

Metrics used to determine the success of healthcare are different from those used for other types of businesses, which solely focus on financial returns in the form of profits. A broader set of metrics around “value creation” for stakeholders (employees, suppliers, managers, financiers, customers, and the local community) should be how organizational performance is evaluated.

Stakeholders are individuals who have an interest in decisions made in the healthcare industry and its subsidiaries. Businesses need to find ways to engage stakeholders, clarify their purpose beyond profits, clarify to whom they are accountable, and clarify how they are going to treat others to foster the kind of cooperation they need to generate and sustain value over time. Stakeholder Theory is a view of capitalism that stresses the interconnected relationships between a business and its customers, suppliers, employees, investors, communities, and others who have a stake in the organization. The ultimate purpose of any healthcare entity is to provide a service to the community it serves.

Stakeholder Theory in Healthcare

Healthcare systems’ hallmarks are things like quality, access, innovation, and prevention. However, affordability and fiscal limits are also important. With the soaring costs of US healthcare, importance is placed on financing care, creating a system that is sustainable and maintains high quality, and innovation. Markets provide a powerful mechanism for aligning the interests of organizations and patients and ensuring that new innovations align with the community’s needs. Properly functioning markets have great efficiency, create powerful connections between patients and providers, generate new innovations that continue to improve the quality of care, and help reduce waste. Waste comes from a variety of sources and patterns of behavior, not only via replication of services and unnecessary treatment but also administrative costs, as well as irresponsible and wasteful behavior by patients. There remains a need to create a system that better serves the interests of a variety of key stakeholders.

Identifying Stakeholders and Their Interests

Stakeholders have a vested interest in the changes within the healthcare sector. Whether they are community patients, providers, payors, policymakers, donors, or investors, they are affected by the operational performance of the organization. The principles of engaging stakeholders include:

- Know who the stakeholders are, both internally and externally

- Build trust with stakeholders through open communication, transparency, and data

- Define ways to serve stakeholders

- Execute a stakeholder strategy (financial impact) to build creditability

- Build a sustainable long-term operating model that creates value for stakeholders through standardization, metrics, and providing feedback

The ACA Responsibility

The Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA) increased health insurance coverage for the uninsured and underinsured through health insurance markets. The delineated principles of this reform included:

- Protect citizens’ financial health (bankruptcy due to catastrophic illnesses)

- More affordable insurance (reducing administrative costs, removing unnecessary testing, and limiting premium charges for certain populations)

- Aim for universality

- Made coverage portable

- Guaranteed choice of plans and providers (allowing individuals to keep their current plans)

- Focused on prevention and wellness

- Improve safety and quality

- Long-term financial sustainability (reducing costs, improving productivity, and adding new revenue sources)

Places where ACA improved access include:

- Children are allowed to stay on their parent’s health insurance policies until they turn 26 years old.

- Children 19 and under cannot be turned down for coverage due to a pre-existing condition.

- Preventative services are provided without cost-sharing.

- Coverage can no longer be rescinded by the insurance company for any reason other than fraud.

- Incentives are provided for providers who work in underserved areas.

- Lifetime limits cannot be placed on any essential health coverage.

- Small businesses can provide health coverage and receive tax credits (up to 35%).

- Seniors who are Medicare Part D eligible can receive a tax-free $250 rebate check.

- Insurance companies must justify unreasonable rate increases (10% or more).

- Consumers can appeal a denied claim with an outside reviewer.

Many contend that the ACA falls short in its reform. However, many of the shortcomings of the ACA were due to the lack of commitment by the states. There were 12 states (Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kansas, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Wisconsin, and Wyoming) that chose not to expand Medicaid coverage, thereby negating the ability to advance health equity. For example, Mississippi chose not to expand using federal matching funds under the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, despite having more than 300,000 individuals who could not afford health insurance and were not qualified for Medicaid. Although former Attorney General Jim Hood was in favor of the expansion, former Governor Phil Bryant sued the federal government, claiming the ACA was unconstitutional. Despite losing millions of dollars caring for uninsured Mississippians each year, the governor chose to “…look at health care as an economic driver…like the automobile industry.” There was also a troubled debut of the federally run insurance marketplaces and state-run programs (Campbell, 2018). The Mississippi marketplace offered very few options that were accepted by very few healthcare entities and often did not reimburse claims for long periods. This poorly supported model would lead one to believe that the ACA was a failure; however, the fault lies with the states that did not support it and the political parties that refused to put citizens before political alliances.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act

Partisan Elements of the PPACA

“Beyond analyzing the rhetoric used to describe healthcare reform,” importance should be placed on examining the legislation bill itself for clues as to its partisan or bipartisan nature. “The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) contains progressive insurance reform and increased fees and burdens on employers, but the bill also incorporates some forward-thinking delivery-side reforms that received bipartisan support (Frakes, 2012).”

A. Insurance Reform

Democrats have publicly denounced the payer community for focusing on profits rather than patients and simultaneously producing barriers to achieving universal coverage. Democratic control of both Congress and the Presidency after the 2008 elections finally offered some opportunity to pass massive insurance industry reforms. The PPACA contained several partisan provisions aimed at negating the market power of insurance companies. Some provisions included severe taxes on insurers and allowed adult dependents to remain on their parent’s coverage until the age of 26. It also established the minimum essential benefits that plans must provide. The White House and Congressional Democrats drafted the bill, which targeted health insurance reform, and this legislation made a strong partisan statement (Frakes, 2012).

B. Employer Penalties

While the PPACA subjects businesses to increased restrictions, requirements, and fees, it allowed the Democrats to reshape employer participation within the insurance industry. Shifting employer participation away from the old model of voluntary, flexible employer-sponsored coverage, a mandate was also added that required employers to provide health insurance coverage to their employees. Section 9006 of the PPACA required businesses to issue 1099 IRS tax forms to any individual or corporation from whom they purchased a good or service worth over $600 within a given tax year. This provision was criticized for being burdensome and time-consuming. However, Congress repealed the provision in early 2011 before President Obama signed the measure into law (Frakes, 2012).

C. Bipartisanship Reform

The trending bipartisan goal that unites both sides of the aisle is the focus on increasing healthcare quality at a lower cost, which is inextricably linked. The promotion of the accountable care shared savings program has gained bipartisan support. Providers are incentivized to produce specific health outcomes and high patient satisfaction. Alternatively, increases in cost resulting from care are the financial responsibility of the provider. The PPACA includes a shared savings model in the form of Accountable Care Organizations (“ACOs”), a shared savings structure for Medicare beneficiaries, and has gained bipartisan support. Lastly, strong bipartisan support exists for the inclusion of health information technology within healthcare delivery. Large-scale political conflicts are brutal, and every congressional member’s votes and statements are available online. These factors present challenges to crafting a piece of healthcare legislation representative of varying opinions and bipartisan support (Frakes, 2012).

———————

The Affordable Care Act

Effect on Availability of Affordable Health Insurance and Access to Care

Years after the ACA was signed into law on March 23, 2010, it has had its clearest and most measurable effects on the availability of health insurance for the American people and access to care. According to the US Department of Health & Human Services (2022), the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) show a “record-breaking 21 million people in more than 40 states and territories gained healthcare coverage thanks to the ACA’s expansion of Medicaid to low-income adults under 65. The total enrollment for Medicaid expansion, Marketplace coverage, and the Basic Health Program in participating states has reached an all-time high of more than 35 million people as of early 2022.”

The ACA has improved the availability of health insurance and access to care by providing states with the option to expand Medicaid programs to include all adults with incomes at or below 138% of the federal poverty level (that translated to $17,130 for a single person and $35,245 for a family of four in 2021). States that chose not to expand cited concerns about funding once federal funds were withdrawn. Several issues that originally plagued the ACA rollout have been improved. The federal marketplaces now seem to be functioning adequately. The number of canceled policies has declined, and marketplaces have offered accessible and affordable alternatives. Lastly, some new marketplace plans restrict access to providers to control costs. While good efforts to improve the process are making strides, many who purchased marketplace plans have substantial deductibles and copayments to minimize premiums, leaving participants with large out-of-pocket expenses and limited access to services (Blumenthal et al., 2015).

The ACA and the Health Care Delivery System

The most aggressive efforts in the history of the nation to address the problems of the delivery system need to focus on approaches to improving healthcare delivery, including:

- changes in the way the government pays for health care,

- changes in the organization of health care delivery,

- changes in workforce policy, and

- changes intended to make the government more nimble and innovative in pursuing future healthcare reforms.

Changes in Payment

The ACA embraced efforts to move away from volume-based, fee-for-service reimbursement and push towards outcome-driven payment models with compliance incentives.

-

Reduce Medicare Readmissions

Hospitals were subjected to financial penalties for higher-than-expected rates of readmissions of Medicare beneficiaries within 30 days, starting in October 2012. Healthcare entities were frustrated because the cause of readmission was not taken into consideration in many cases. For example, a patient who is recovering from being discharged the previous week has an automobile accident and is readmitted. The cause of readmission had no bearing on the initial incident. However, since the inception of this program, 30-day readmission rates nationally have declined drastically among Medicare beneficiaries. According to Blumenthal et al. (2015), “the appropriateness of current readmission measures has been questioned because of evidence that safety-net hospitals and large teaching hospitals may be unfairly penalized under the program owing to the social and medical complexity of their patient populations.”

-

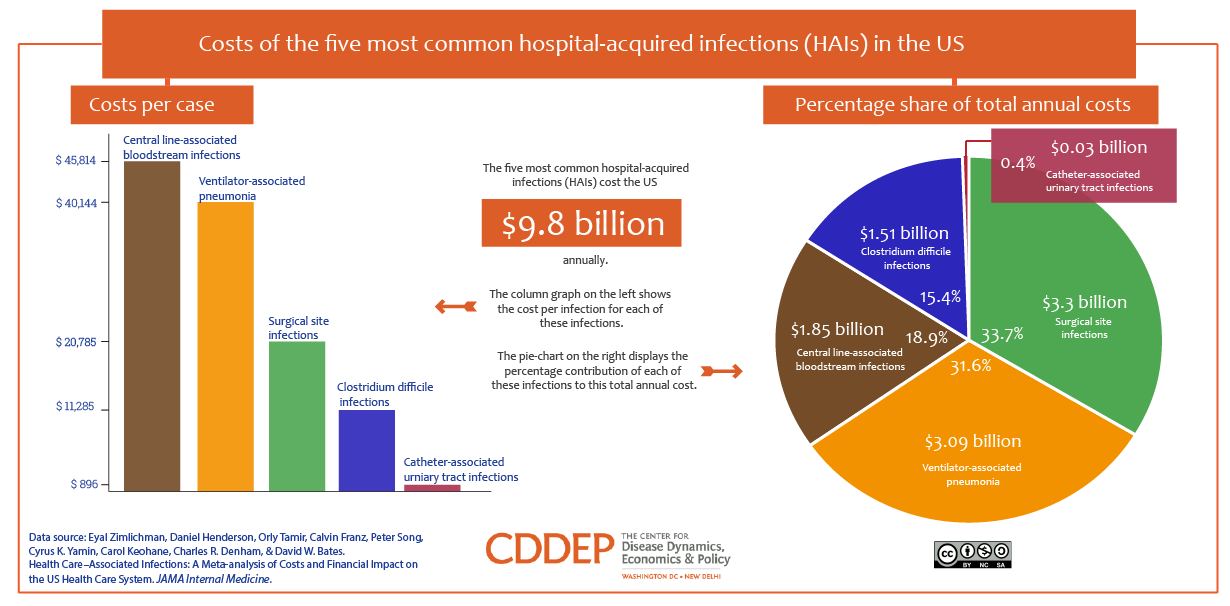

Reduce Hospital-Acquired Conditions

The ACA expanded a previous CMS program that penalized hospitals for avoidable threats to the safety of Medicare patients, coined never events. Under the ACA program, a hospital may lose 1% of Medicare payments if it performs in the lowest quartile regarding rates of hospital-acquired conditions, including avoidable infections, adverse drug events, pressure ulcers, and falls. This payment program strives to improve patient safety. The Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) noted a documented decline in composite rates of hospital-acquired conditions nationally and estimates that these safety improvements prevented deaths and saved healthcare costs.

-

Value-Based Payment Programs for Hospitals and Physicians

Since the passage of the ACA, value-based payment models have revolutionized the way healthcare systems receive payments. Value-based programs provide incentives for hospitals and physicians to improve their performance on a variety of quality and cost metrics other than hospital-acquired conditions and readmissions.

CMS’s five original value-based programs have the goal of linking provider performance of quality measures to provider payment:

There are other value-based programs:

| LEGISLATION | PROGRAM |

| ACA: Affordable Care Act | APMs: Alternative Payment Models |

| MACRA: Medicare Access & CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 | ESRD-QIP: End-Stage Renal Disease Quality Incentive Program |

| MIPPA: Medicare Improvements for Patients & Providers Act | HACRP: Hospital-Acquired Condition Reduction Program |

| PAMA: Protecting Access to Medicare Act | HRRP: Hospital Readmission Reduction Program |

| HVRP: Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program | |

| MIPS: Merit-Based Purchasing System | |

| VM: Value Modifier or Physician Value-Based Purchasing Program | |

| SNFVBP: Skilled Nursing Facility Value-Based Purchasing Program |

-

Bundled Payments

The Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) encourages clinicians to participate in alternative payment models (APM), such as bundled payments. Bundled payments shift the financial risk to providers, further urging them to focus on cost-efficient care and reduced waste. Under the bundled payment model, providers receive a single payment for a specified set of hospitalization, physician, and post-acute care services related to a given procedure or condition (Franco, 2017).

Changes in the Organization of Health Care Delivery

-

Accountable Care Organizations

The ACA encourages healthcare providers to form new organizational arrangements called accountable care organizations (ACOs). It intends to promote the integration and coordination of ambulatory, inpatient, and post-acute care services and to take responsibility for the cost and quality of care for a defined population of Medicare beneficiaries. It was perceived that ACOs would serve as a bridge from fragmented fee-for-service care to integrated, coordinated delivery systems. However, challenges with the early implementation of ACO caused over 100 people to drop out of Medicare and commercial plans.

-

Primary Care Transformation

One of the ACA’s focuses is to improve the delivery of primary care by supporting a variety of programs, like the Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative. It is an innovative payment and organization model designed to control expenses and improve the quality of care through emphasized care coordination, improved chronic disease management, greater access to primary care, and administrative simplification. It has shown a significant reduction in emergency department visits and inpatient hospitalizations.

———————

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act was a comprehensive healthcare reform law enacted in 2010 and also known as the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The ACA had three primary goals.

- Improving access to healthcare coverage through more affordable options and subsidies (“premium tax credits”).

- Expand the Medicaid program to cover all adults with income below 138% of the FPL. Despite federal funds to support the Medicare expansion, several states did not adopt the expansion (Texas, Wyoming, Kansas, Wisconsin, Mississippi, Alabama, Tennessee, Georgia, Florida, North Carolina, and South Carolina).

- Support initiatives designed to lower the costs of healthcare.

Initially, one initiative under the ACA provided increased Medicare reimbursements to pay primary care physicians for two years. This helped increase the number of primary care appointments for Medicare patients (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2022). In addition to extending coverage and improving preventative healthcare access, the ACA also enforced:

- Requirements for employee coverage for companies with 50 or more full-time employees

- Eliminated rejection of coverage based on preexisting conditions for children

- Create a state-based Health Exchange for individuals to gain coverage

- Create essential health benefits packages providing comprehensive coverage for a set of services

- Eliminated lifetime capitations for coverage

- Shifted focus on quality outcomes and reduced waste

An individual mandate requiring US citizens to maintain healthcare coverage or be penalized (KFF, 2013). Penalties were increased annually. All of the ACA requirements can be found here.

Single-Payer Healthcare

The first bill proposing a single-payer system in the U.S. was endorsed by President Harry Truman in 1943 and would be funded through payroll taxes. Although the bill did not come to fruition, Medicare was enacted in 1965 and embodied the single-payer model. The architects of Medicare saw it as the cornerstone of a national health insurance system and believed it would eventually expand to cover the entire population. Support for the single-payer system gained momentum again in the early 1970s among liberal Democrats such as Senator Ted Kennedy (D-MA). While policymakers were able to pursue incremental expansion through Medicaid, Medicare expansion has yet to happen. Groups such as Physicians for a National Health Program support the single-payer approach (Oberlander, 2016).

Although the ACA was the largest piece of healthcare reform with considerable achievement, healthcare coverage continues to be out of reach for many Americans, specifically those in poorer states, due to a lack of marketplace choices. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics, there were 31.6 million people of all ages without healthcare coverage in 2020, and 31.2 million were under the age of 65 (Cha & Cohen, 2022). While the allure of reducing healthcare spending is enticing, one of the biggest drawbacks to a U.S. single-payer program is the fierce resistance from conservatives that charge these programs to be “socialized medicine” with “death panels.” There is a belief that large-scale tax increases would need to fund a single-payer program rather than trim government spending on military defense. The combination of prevailing anti-tax sentiment with the required substantial overhaul of the current system leaves the task of adopting a single-payer system daunting. Not to mention the needed support from the U.S. Senate to secure enough votes to overcome a filibuster. With each election comes uncertainty concerning healthcare reform and ongoing support. Preserving and strengthening the ACA and Medicare while addressing the underinsurance and affordability of coverage could be just as difficult as establishing a single-payer system.

Based on the current lack of federal funding for healthcare and the exorbitant costs associated with it, the question remains whether or not the government could absorb the costs of a single-payer system. Although Senator Bernie Sanders proposed a single-payer bill in 2016, estimating $14 trillion over a decade, economists estimate costs to be much higher. According to the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (2019), economists estimated that a single-payer healthcare system would cost the federal government $27.7 trillion through 2026, the Urban Institute estimated a $32 trillion cost over the same period, and the American Action Forum calculated that it would cost the federal government $36 trillion through 2029. On average, the estimated cost to the federal government would roughly be $28–32 trillion over a decade. Representative Pramila Jayapal’s Medicare for All Act proposed in 2019 and 2021, has failed to pass. Medicare for All is supported by 69 percent of registered voters, including 87 percent of Democrats, the majority of Independents, and nearly half of Republicans. Additionally, over 50 cities and towns across America have passed resolutions endorsing Medicare for All.

Future Healthcare Law

Trends in healthcare spending have followed a steep upward trajectory accompanied by a global pandemic, rapidly growing scientific precision, and technical sophistication. According to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services National Health Expenditure Data (2021), the U.S. healthcare system spent upwards of $4.3 trillion, or 18.3% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Not only did Medicare and Medicaid spending grow by 21% and 17%, respectively, but private health insurance and out-of-pocket expenditures also grew by 28% and 10%, respectively. National health spending is projected to grow to reach $6.2 trillion by 2028 (CMS, 2021). Sadly, U.S. spending is comparatively high in relation to other developed countries, yet outcomes are not superior to these other countries.

In 2023, Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy vowed to avoid raising the debt limit on entitlement programs like Social Security and Medicare without first issuing budget cuts to the programs. Reforms to these programs are likely to come, including cuts that would decrease reimbursements for services and are expected to impact the quality of care patients will receive. The House Freedom Caucus is a group of 50 Republicans that is tackling excessive government spending, including healthcare. McCarthy granted them significant concessions to secure his seat as Speaker of the House. Republicans propose converting Medicaid and Affordable Care Act subsidies to block grants, which would cut spending by $3.6 trillion over 10 years (Lalljee, 2023). Some Republicans have called for the complete elimination of Social Security. In 2023, Florida Senator Rick Scott proposed a plan to require Congress to renew Social Security and Medicare every five years. However, Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell stated, “Unfortunately, that was the Scott plan; that’s not a Republican plan (Bailey, 2023).” While funds for entitlement programs stay at the forefront of budget concerns, other areas of the national federal budget seem to be increasing with no opposition. For example, the 2023 National Defense Authorization Act defense budget was increased by 8%. President Joe Biden has signed the Fiscal 2023 National Defense Authorization Act into law, allotting $816.7 billion to the Defense Department. Funding for this increase is not yet clear (Harris, 2022). This is important to note when budget cuts are being made to the national federal budget. Comparatively speaking, defense spending is over half of the U.S. discretionary spending budget, while healthcare remains at an average of 5% (not including the 8% allocated for veterans’ benefits). This continues to transfer healthcare costs for services back to those not covered by Medicare/Medicaid. The majority of healthcare spending went towards in-patient hospital care (over 30%) (Kurani et al., 2022). To lower healthcare costs, the focus has heavily shifted to preventative care.

Preventative Care

One way to prevent the enormous costs associated with treatment for acute illnesses and chronic healthcare events is to shift the focus from treatment to prevention and early intervention (Sage & McIlhattan, 2014). Healthcare demands that we “do more with less.” Throwing money at a problem no longer suffices, and patients expect quality. Trends in unhealthy behaviors and chronic disease have enhanced the need for population health. The COVID-19 pandemic has also pushed the government to be more involved in healthcare. Inventing and funding new technologies could alleviate some of the financial burdens. Unfortunately, most of what is considered “healthcare law” is anchored in legal issues relating to professionals, facilities, private insurance, public programs, corporate structures, and the use or withdrawal of life-giving technology. Health policy needs to reevaluate and accommodate changing geographic and service boundaries, new professional settlements, and evolving financial practices.

A. Dyadic care

“The physician-patient relationship is a member of a special class of legal relationships called fiduciary relationships. Through the creation of fiduciary duties, the law recognizes that there are relationships in which the parties inherently have unequal power (Witherell v. Weimer, 1981).” This relationship’s foundation is based on the theory that the physician-patient relationship has the following structure: the physician is skilled and experienced in those subjects about which the patient is not, but may depend on their health or even their lives. Therefore, the patient places great confidence and faith in the professional advice and acts of the physician. The physician is expected to recommend treatments based only on the patient’s medical and psychological needs. Witherell v. Weimer, 421 NE2d 869 (1981).

- The physician-patient relationship is fiduciary, and the patient’s interests must be a priority. This stands in contrast to the legal rule of caveat emptor (“let the buyer beware”). Typically, the law assumes the buyer and seller have knowledge of and access to the same information and possess bargaining power. Fiduciary duty extends to all aspects of the physician-patient relationship. This includes breaching the financial aspects of the fiduciary duty to a patient, which can subject the physician to liability under the law.

B. Physician control

Power and accountability in healthcare reside mainly within the self-regulating medical profession. This indicates that physicians decide what treatments patients will receive. The healthcare practitioner who generates a medical record after making a physical or mental examination of, or administering treatment to, any person is considered the owner of the medical record. This is especially the case when medical charts are kept on paper in a file cabinet. Physicians serve as gatekeepers by determining the scope and intensity of healthcare services. As a result of this structure, medical services are low in variety, accessibility, and measurable benefit. Physicians most often bear moral and financial responsibility in the event that something goes wrong, which can breed bias and fear in the profession.

Information and authority are more diffused with the evolution of electronic medical records. Displaced individuals during Hurricane Katrina, along with destroyed medical records, encouraged the widespread adoption of interoperable electronic systems and allowed a patient’s medical history to be accessed anywhere. Electronic health records (EHR) expenditures in the US grew an annual average of 5.4% from 2015 to 2019, totaling $14.5 billion in 2019 (Jercich, 2020). US expenditures on EHRs are forecast to total $19.9 billion in 2024 (Jercich, 2020). However, according to Huynh and Dzabic (2020), interoperability of EHRs would cut health costs by $30 billion through streamlined patient-centered care.

C. Hospital walls

Hospitals are confined settings where patients receive treatment for serious illnesses. They have specialized technology and a clear professional hierarchy. Patients are considered vulnerable, and their care is considered crucial, but the history of hospitals is more focused on charity than business, despite the large number of resources and financial benefits they generate. Therefore, hospitals often have a feudal-like community structure rather than a business-like structure, including in terms of safety and quality.

Hospitals represent a closed environment in which the sickest patients live as well as receive care, with captive technology and a strict hierarchy of professional authority. Hospitalized patients are assumed to be vulnerable, and the care they receive is seen as life-saving. However, the hospital’s history is more charitable than corporate, notwithstanding the considerable resources the sector consumes and the financial rewards it generates. As a result, the hospital often functions as a feudal community rather than an industrial organization, including with respect to safety and quality. Historically, independent physician decision-making has taken precedence over administrative efficiency, leading to decentralized governance among clinical departments, which is delegated to medical staff committees and verified through compliance with private accreditation standards. Physicians do not hold positions as owners, managers, employees, or suppliers, but instead form an internal nobility with their own power dynamics and methods for distributing rewards and resolving conflicts. However, health services obtained through schools, faith organizations, workplaces, and community groups are different. Physicians are not typically in charge in these settings. Other professionals, such as nurses, pharmacists, social workers, and clergy, exercise their authority and follow their own preferences. Health can also be a significant aspect of social networks that lack a clear hierarchy or leadership but still require oversight to prevent harm and misuse of resources.

D. Third-party payment

Healthcare coverage typically falls into three categories: governmental, employer-provided, or private plans.

- Government plans:

- Medicare- Individuals 65 years and older

- Medicaid- state-run plan for low-income families, qualified pregnant women, children, and individuals with disabilities

- TRICARE- federal program for military personnel

- CHAMPVA- federal program for disabled veterans and their dependents

- Employer-provided plans are provided to employees who work 30 or more hours per week

- Private plans are provided by the private health insurance industry and are not run by the government but are regulated at the state and federal levels.

- COBRA allows eligible former employees and their dependents the option to continue group health insurance coverage at their own expense for a period of time, usually up to 36 months. It is also available for individuals turning 26 and no longer covered by their parent’s insurance plan, part-time workers, and the self-employed.

Hospital care, services provided by licensed health professionals, and treatments that require a physician’s prescription are typically covered by health insurance, while areas such as nutrition, fitness, and stress management are often excluded. The justification for these fixed categories is practical, as they tend to be more expensive and less flexible, making insurance both necessary and manageable. For companies offering health coverage as an employee benefit, this aligns with providing financial security. For publicly funded programs like Medicare and Medicaid, this reduces the potential for abuse. However, these arguments can be circular, as insurance may contribute to high prices, and reactive care may be more costly and less effective than proactive prevention and early treatment. Only a few health insurance plans, known as health maintenance organizations, attempt to address these issues. The rest reinforce the medical establishment through provider contracts in private coverage and reimbursement systems in public coverage.

Healthcare law will require a more adaptable approach to easing the financial strain of healthcare. Most transactions will not be covered by traditional insurance. Healthcare law must determine the responsibilities of these intermediaries to end-users based on the contracts they offer to the public and the impact they have on service providers. Instead of offering fixed coverage categories, insurance may provide fixed subsidies in case of illness or injury, giving policyholders more control over how the funds are used (similar to disability insurance). This approach is more attractive because insurers can no longer rely on physician judgment as a necessary proxy.

E. Physician-extending technology

Many “mid-level” providers have been seen as physician extenders rather than independent professionals. However, this assumption is disrespectful to their skill set and knowledge-based. The objective of employing mid-level providers is to enhance or supplement the services provided and billed by physicians, not to diminish their skills or replace them. When new devices, treatments, or drug formularies are created, physicians act as “learned intermediaries” for patients regarding the product’s risks. However, the US pharmaceutical market is unique in its ability to market directly to consumers. Combined with the push to engage the patient as part of the healthcare decision-making team, it is unclear who possesses “prescriptive authority” under the law.

With emerging new technologies being “reimbursable” by health insurance, access to third-party payment creates incentives for providers to use new products/devices but high additional costs for the patient. However, many modern technologies are extensions of the physician’s practice, such as the ability to access hospital and clinic notes or diagnostic laboratory results.

F. Self-monitoring

Patients are able to easily obtain a home pulse oximeter, a home blood pressure monitoring system, a wristband blood pressure monitor to be worn when exercising, and a home defibrillator. A compact device can be attached to an individual’s inhaler, which records each time the inhaler is used and its location. The recorded data is then wirelessly transmitted to the individual’s smartphone. Similar devices enable people with chronic conditions to self-monitor various health parameters, such as blood glucose levels, ECG data, body temperature, heart rate, and blood pressure. Electronic platforms, smartphone apps, and computerized systems are becoming increasingly prevalent, empowering individuals to take a more proactive role in managing their health and wellness. There is a wide range of informational and educational tools available, each performing diverse functions. Symptom checkers from WebMD and Aetna allow individuals to learn about potential causes of symptoms. A drug interaction checker through CVS informs individuals about potential drug interactions with prescription and over-the-counter medications.

There are countless other applications that encourage healthier habits, track pregnancy, customize fitness and weight-loss plans, as well as track sleep patterns, physical activity, and calories burned. Most apps are downloaded to personal smartphones and can offer a mobile-connected recordkeeping service for individuals. Individuals can access their medical records, such as Epic Systems’ MyChart, through digital portals, allowing them to view lab/test results, immunization history, prescription lists, family medical histories, and data from self-monitoring.

G. Communication and consultation

Some apps allow patients to search for physicians, hospitals, and other healthcare providers, schedule appointments, and check in remotely. Some apps allow individuals to consult a physician on demand for a nominal fee of $40. The ability to access medical records also allows for real-time communication between the patient, office staff, and physician via patient portals. Patients can leave messages directly for the nurse or provider and receive responses without communicating with office personnel. Eliminating this link in the process makes communication more efficient.

H. Retail Medical Clinics

Retail medical clinics offer accessible and affordable health services, typically provided by mid-level practitioners, without the need for appointments and at fixed prices. Clinics are commonly located in chain drug stores like Walgreens and CVS, supermarkets like Publix, or big-box retailers like Walmart and Target. Although they are not yet a major source of primary care, they have had a significant impact on COVID vaccination coordination and distribution. Retail clinics provide basic medical services for minor illnesses and injuries at a lower cost and without the need for appointments. While they may provide similar services to what a private physician’s office would offer, they are typically not considered a replacement for a traditional doctor-patient relationship.

Sentinel Legal Issues

Sentinel issues in the healthcare industry involve various aspects of the healthcare workforce, such as restrictions on licenses for primary care providers, obstacles to telehealth, and limitations on community health workers. Other issues encompass approvals of medical products, liability, and malpractice risks, insurance coverage and payment, and privacy and security of health information. Several issues have exacerbated the need for providers, including the aging baby boomer population, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the number of people obtaining mandated healthcare coverage. According to predictions by Heiser (2021) from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), the United States could see an estimated shortage of between 37,800 and 124,000 physicians by 2034. The global pandemic highlighted severe disparities in access to healthcare services and revealed weaknesses in the healthcare system.

A. Nurse Scope of Practice

Licensing laws in most states limit the independent delivery of primary care by nurse practitioners (NPs). To provide care, some states mandate that NPs enter into collaboration agreements with physicians. For instance, in New Jersey, NPs must establish a joint protocol with a collaborating physician to prescribe medication. In other states, NPs require formal supervision, delegation, or physician-led management. Restrictive practice laws usually outline the ratio of physicians to NPs, require supervising physicians to be present on site (e.g., at a retail clinic) for a certain number of hours, or limit the number of sites that a single physician can oversee. While some states have loosened these restrictions or allowed NPs full autonomy to practice, it has been met with great opposition from medical professional organizations.

B. Community Health Centers

C. Over-the-Counter (OTC) Drugs

- Avoiding the need for a doctor’s visit: By allowing consumers to purchase and self-medicate with OTC drugs, they can avoid the cost of a doctor’s visit, which can be substantial.

- Lower cost of medication: OTC drugs are typically less expensive than prescription drugs because they do not require a prescription and can be sold directly to consumers.

- Reduced health insurance costs: Using OTC drugs can reduce the burden on the healthcare system and lower the overall cost of healthcare, which can result in lower health insurance costs for consumers.

- Increased competition: The availability of OTC drugs creates competition in the marketplace, which can lead to lower prices for consumers.

- Improved health outcomes: By allowing consumers to treat common illnesses and conditions at home, OTC drugs can improve health outcomes and prevent the need for more costly medical interventions.

D. Home Testing

Home testing options have expanded rapidly in the last two decades. Many consumer diagnostics are regulated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) using the risk-based approach to classifying medical devices authorized by the FDA Modernization Act of 1997. However, testing is being heavily marketed directly to consumers, sometimes without proper FDA clearance. Home testing kits can provide information about DNA genealogy, potential allergies, illegal drug use, fertility, pregnancy, STDs, colorectal cancer, and the inheritance of breast or cervical genes. Home testing kits were revolutionized by the free COVID-19 kits provided to American citizens.

Without proper FDA clearance, the FDA warns of accuracy flaws in processing results and the estimates of disease risk for customers. However, its availability provides access to consumers without the need for an appointment or insurance approval. The results are also private and owned by the consumer. If the consumer purchases genetic testing from a home kit, there is no medical record validating that diagnosis. If that individual decides to upgrade their cancer policy after receiving at-home kit results, there is no confirmed medical diagnosis to disclose as a pre-existing condition. A medical diagnosis is typically made by a licensed healthcare provider based on a comprehensive evaluation of a patient’s symptoms, medical history, and results from various diagnostic tests, including laboratory tests.

It’s important to note that at-home medical kits can be useful tools for monitoring health, but they should not be used in place of a formal medical evaluation by a licensed healthcare provider. If the results of an at-home test are positive or concerning, it’s recommended to follow up with a doctor or healthcare professional for a more complete evaluation and to receive an accurate diagnosis.

Privacy and Security of Personal Health Data

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) is a federal law in the United States that was enacted in 1996. It provides a set of national standards to protect the privacy and security of individuals’ protected health information (PHI). The Department of Health and Human Services was given the authority to enforce HIPAA compliance.

HIPAA requires healthcare providers, health plans, and healthcare clearinghouses to implement administrative, physical, and technical safeguards to ensure the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of electronically protected health information (ePHI). HIPAA also gives individuals the right to access and receive a copy of their health information, as well as the right to request that their information be amended if it is inaccurate or incomplete. HIPAA is important for maintaining the privacy and security of individuals’ health information, as well as ensuring that this information is only used for authorized purposes. Failure to comply with HIPAA can result in significant fines and legal penalties. The largest HIPAA settlement in 2021 was against Excellus Health Plan for a penalty of over $5 million for a breach of over 9K patient records in 2015 (HIPAA Journal, 2022). A study from the University of Minnesota and the University of Florida measured attacks on healthcare delivery organizations from 2016 to 2021, and the results suggest ransomware attacks on healthcare delivery organizations are increasing in frequency and sophistication, further exacerbating HIPAA violations. Attacks have doubled while personal health information exposure increased more than 11-fold, from approximately 1.3 million in 2016 to more than 16.5 million in 2021 (McKeon, 2023)

The HIPAA Right of Access standard, specified in 45 C.F.R. § 164.524(a), grants individuals the privilege to examine, obtain, and receive a copy of their own protected health information kept in a designated record set. Within 30 days of receiving a request from an individual or their authorized representative, the health records must be provided. A reasonable fee, based on the cost of reproduction, may be charged for the copies requested. Although a request for access to health records may be declined, this can only occur under specific and rare circumstances. Some of these circumstances include:

- Psychotherapy notes: A covered entity may deny an individual’s request for access to psychotherapy notes, which are separate from the rest of the individual’s medical record.

- Information compiled for legal proceedings: A covered entity may deny an individual’s request for access to PHI if it was compiled in anticipation of, or for use in, a civil, criminal, or administrative proceeding.

- Information that could cause harm: A covered entity may deny an individual’s request for access to PHI if the disclosure of the information could cause serious harm to the individual or another person.

- Information that is subject to law enforcement or national security restrictions: A covered entity may deny an individual’s request for access to PHI if the information is restricted by law enforcement or national security requirements.

- Information that is protected by a privilege: A covered entity may deny an individual’s request for access to PHI if the information is protected by a privilege, such as attorney-client privilege or physician-patient privilege.

Other general privacy laws include the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act of 1986 and the Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986. The Computer Fraud and Abuse Act of 1986 prohibits unauthorized access to protected computers and networks as well as unauthorized damage to computer systems. It also criminalizes the unauthorized distribution of malicious software and the unauthorized interception of electronic communications. The Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986 governs the interception of electronic communications, including unauthorized access to stored electronic communications. Health information technology is governed by various federal and state laws and regulations, including the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), which provides specific protections for electronically protected health information. However, the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act of 1986 and the Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986 were enacted before the widespread use of telehealth and mobile medical apps and may not fully address the privacy and security risks associated with these types of apps.

Therefore, while the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act of 1986 and the Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986 may provide some protections for individuals using mobile medical apps, they may not be sufficient to fully address the privacy and security risks associated with these apps. It’s important for individuals to be aware of the privacy and security risks associated with mobile medical apps and to carefully review the privacy policies and terms of use for these apps before using them.

Conclusion

Innovations in healthcare are being leveraged to help curtail the excessive costs of healthcare delivery. It’s worth noting that the healthcare system is a complex and constantly evolving area, and there are many different opinions on the best way to reform it. There is no quick fix. The global pandemic put urgency on healthcare reform. The newest legislative reform will ensure no individual or family pays more than 8.5 percent of their total household income for their health care insurance. The Health Care Improvement Act of 2021 was an amendment to the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act to reduce healthcare costs and expand healthcare coverage to more Americans, requiring the Secretary of Health and Human Services to create a low-cost public healthcare option. It aims to reduce healthcare costs and protect citizens with preexisting conditions. The Health Care Improvement Act of 2021 would lower costs for working families by:

- Capping healthcare costs on the ACA exchanges

- Establishing a low-cost public health care option

- Authorizing the federal government to negotiate prescription drug prices

- Allowing insurers to offer health care coverage across state boundaries

- Supporting state-run reinsurance programs

- Incentivizing states to expand Medicaid

- Expanding Medicaid eligibility for new moms

- Simplifying enrollment

- Increasing Medicaid funding for states with high levels of unemployment

- Funding rural healthcare providers

- Reducing burdens on small businesses

Key Takeaways

- The Affordable Care Act (ACA): The ACA, also known as Obamacare, was signed into law in 2010 and aimed to increase access to healthcare and reduce costs. Some of the key provisions of the ACA include the expansion of Medicaid, the creation of health insurance exchanges, and the requirement that all individuals have health insurance coverage.

- Drug pricing: There has been a growing concern about the high cost of prescription drugs in the United States. In response, there have been efforts to increase transparency in drug pricing and to allow the government to negotiate drug prices directly with pharmaceutical companies.

- Mental health and addiction services: Mental health and addiction services have long been underfunded and stigmatized in the United States. There have been recent efforts to increase access to mental health and addiction services, including the expansion of telemedicine and the integration of mental health services into primary care.

References

- Bailey, P. (2023). ‘That’s not a Republican plan’: McConnell distances GOP from Scott on Social Security, Medicare sunset plan. USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2023/02/10/mitch-mcconnell-scott-sunset-medicare-social-security/11227447002/

- Blumenthal, D., Abrams, M., and Nuzum, R. (2015). The Affordable Care Act Years Later. New England Journal of Medicine, 372:2451–2458. doi 10.1056/NEJMhpr1503614

- Campbell, L. (2018). Gov. Bryant quietly in talks about a Medicaid expansion plan for Mississippi. Mississippi Today. https://mississippitoday.org/2018/12/19/gov-bryant-quietly-in-talks-about-a-medicaid-expansion-plan-for-mississippi/

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2022). National Health Expenditure Data Fact Sheet. https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/statistics-trends-and-reports/nationalhealthexpenddata/nhe-fact-sheet

- Cha, A. E. & Cohen, R. A. (2022). Demographic Variation in Health Insurance Coverage: United States, 2020. National Health Statistics Report. Number 169. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr169.pdf

- Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. (2019). How much will Medicare for All costs? https://www.crfb.org/blogs/how-much-will-medicare-all-cost#:~:text=For%20example%2C%20economist%20Kenneth%20Thorpe,(likely%20about%20%243%20trillion).

- Frakes, V. L. (2012). Partisanship and (Un)compromise: A Study of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. 49 Harvard. Journal on Legislation 135. https://harvardjol.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/17/2013/09/Frakes1.pdf

- Franko, M. (2017) Bundle Payments. Fierce Healthcare. https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/finance/industry-voices-future-bundled-payments

- Harris, B. (2022). Congress authorizes 8% defense budget increase. Defense News. https://www.defensenews.com/congress/budget/2022/12/16/congress-authorizes-8-defense-budget-increase/#:~:text=The%20%24858%20billion%20NDAA%20%E2%80%94%20which,produce%20major%20weapons%20systems%20and

- Heiser, S. (2021). AAMC Report Reinforces Mounting Physician Shortage. Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/press-releases/aamc-report-reinforces-mounting-physician-shortage

- HIPAA Journal. (2022). 2020-2021 HIPAA Violation Cases and Penalties. https://www.hipaajournal.com/2020-hipaa-violation-cases-and-penalties/

- Huynh, K. & Dzabic, N. (2020). Industry Voices-Interoperability can cut health costs by $30B. But this needs to happen first. Fierce Healthcare. https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/tech/industry-voices-interoperability-can-reduce-healthcare-costs-by-30b-here-s-how

- Jercich, K. (2020). Hospital EHR spending projected to reach $9.9B by 2024. Healthcare IT News. https://www.healthcareitnews.com/news/hospital-ehr-spending-projected-reach-99b-2024

- Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). (2013). Summary of the Affordable Care Act. Health Reform. https://www.kff.org/health-reform/fact-sheet/summary-of-the-affordable-care-act/

- Kurani, N, Ortaliza, J., Wager, E., Fox, L., and Amin, K. (2022). How has U.S. spending of healthcare changed over time? Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker. https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/u-s-spending-healthcare-changed-time/

- Lalljee, J. (2023). Damaging cuts to Medicare and Social Security are looking more likely with McCarthy as House Speaker. Here’s what it will mean for retirees. Yahoo! News Insider. https://news.yahoo.com/damaging-cuts-medicare-social-security-154534411.html?soc_src=social-sh&soc_trk=fb&tsrc=fb&guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly9sLmZhY2Vib29rLmNvbS8&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAAAQvRHJsTF1tjLGpugP_vE4sDtw6w_lGXzQBZLpMFW_deiQPKO5QXT-m-4Sl4x2br-mCPeOsjDRL9Gt_UvC568UXI7TMBg4wawQ9Ynar4GKhqurJ0MrvIIUTbv_fv0bJ5jC6eq5UGbMqbOTXXjmzzVbdzJdXdzBqFrb-kO4D5fWn

- McKeon, J. (2023). Healthcare Ransomware Attacks More Than Doubled Over Past 5 Years. Cybersecurity News. https://healthitsecurity.com/news/healthcare-ransomware-attacks-more-than-doubled-over-past-5-years#:~:text=In%20total%2C%20the%20researchers%20documented,than%2016.5%20million%20in%202021.

- Oberlander, J. (2016). The Virtues and Vices of Single-Payer Healthcare. New England Journal of Medicine, 374:1401-1403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1602009

- Pollard, M. (2022). Equal Healthcare Act: A Brief Review of Health Insurance Programs and how Healthcare Vouchers Ameliorates many Endemic Issues. Pepperdine Policy Review, 14, 1-26. https://login.ezproxy.lib.uwf.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.uwf.edu/scholarly-journals/equal-healthcare-act-brief-review-health/docview/2685683358/se-2

- Rural Health Information Hub. (2021). Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) and the Health Center Program. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/federally-qualified-health-centers

- Wicks, A. C., & Keevil, A. A. C. (2014). When Worlds Collide: Medicine, Business, the Affordable Care Act and the Future of Health Care in the U.S. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 42(4), 420–430. https://doi.org/10.1111/jlme.12165

- Wilensky, S. E. & Teitelbaum, J. B. (2018). 2018 Annual Health Reform Update. Jones & Bartlett.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2022). About the Affordable Care Act. https://www.hhs.gov/healthcare/about-the-aca/index.html