12 Chapter 12: The Creation of Latin Christendom and Medieval Europe

Once the last remnants of Roman power west of the Balkans were extinguished in the late fifth century CE, the history of Europe moved into the period that is still referred to as “medieval,” meaning “middle” (between). Roughly 1,000 years separated the fall of Rome and the beginning of the Renaissance, the period of “rebirth” in which certain Europeans believed they were recapturing the lost glory of the classical world. Historians have long since dismissed the conceit that the Middle Ages were nothing more than the “Dark Ages” so maligned by Renaissance thinkers, and thus this chapter seeks to examine the early medieval world on its own terms – in particular, what were the political, social, and cultural realities of post-Roman Europe?

The Latin Church

After the fall of the western Roman empire, it was the Church that united Western Europe and provided a sense of European identity. That religious tradition persisted and spread, ultimately extinguishing the so-called “pagan” religions, despite the political fragmentation left in the wake of the fall of Rome. The one thing that nearly all Europeans eventually came to share was membership in the Latin Church (a note on nomenclature: for the sake of clarity, this chapter will use the term “Latin” instead of “Catholic” to describe the western Church based in Rome during this period, because both the western and eastern “Orthodox” churches claimed to be equally “catholic”: universal). As an institution, it alone was capable of preserving at least some of the legacy of ancient Rome.

That legacy was reflected in the learning preserved by the Church. For example, even though Latin faded away as a spoken language, all but vanishing by about the eighth century even in Italy, the Bible and written communication between educated elites was still in Latin. Latin went from being the vernacular of the Roman Empire to being, instead, the language of the educated elite all across Europe. An educated person (almost always a member of the Church in this period) from England could still correspond to an educated person in Spain or Italy, but that correspondence would take place in Latin. He or she would not be able to speak to their counterpart on the other side of the subcontinent, but they would share a written tongue.

Christianity displayed a remarkable power to convert even peoples who had previously proved militarily stronger than Christian opponents, from the Germanic invaders who had dismantled the western empire to the Slavic peoples that fought Byzantium to a standstill. Conversion often took place both because of the astonishing perseverance of Christian missionaries and the desire on the part of non-Christians to have better political relationships with Christians. That noted, there were also straightforward cases of forced conversions through military force – as described below, the Frankish king Charlemagne exemplified this tendency. Whether through heartfelt conversion or force, by the eleventh century almost everyone in Europe was a Christian, a Latin Christian in the west and an Orthodox Christian in the east.

Imperial Control and Foreign Threats to Byzantium

In 600 the empire still laid claim along the southern and eastern shores of the Mediterranean, to most of the lands that Rome had ruled for centuries. But in the East the empire had been suffering recurrent losses to Persia. When Arab expansion began under Umar, the empire was military and financially exhausted. As the 7th century wore on, Arabs captured Syria, Palestine, and Mesopotamia and began a centuries long push into Anatolia. Where the West was concerned the Byzantines were powerless to stop Arab advance in North Africa and Spain. In Italy imperial control was confined to a few outposts around Rome and Sicily. By around 700 the empire was assuming the basic geographic shape it would hold for centuries. As its territory shank, the Byzantines began to look inward. Specifically Byzantine culture came to be increasingly defined by the church. The massive Arab conquests that stripped Byzantium of so much territory also removed Alexandria, Jerusalem, and Antioch form effective contact with Constantinople. Deprived of this contact/stimulus/inspiration Byzantium turned inward and we see the growth of a separate church.

While the losses of territory in Europe were mourned by Byzantines at the time, they proved something of a blessing in disguise to the empire: with its territory limited to the Balkans and Anatolia, the smaller empire had much more coherent and easily-defended borders. Thus, those core areas remained under Byzantine control despite various losses for many centuries to come. The emperor Leo the Isaurian (r. 717 – 741) recruited soldiers to both fight off Arab sieges of Constantinople and to cement control of Anatolia. By the end of his reign, Anatolia was secure from the Arabs and would remain the major part of the Byzantine Empire for centuries.

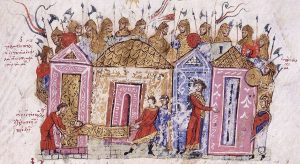

In the Balkans, Slavic tribes proved a major ongoing problem for the Byzantines. A people known as the Avars invaded from the north in the sixth century and raided not just the Balkans but all across Europe, making it as far as the newly-created Frankish kingdom in present-day France. In the eighth century an even more ferocious nomadic people, the Bulgars (for whom the present-day country of Bulgaria is named), invaded. While the Avars had converted to Christianity during the period of their invasions, the Bulgars remained pagan. They destroyed the remaining Byzantine cities in the northern Balkans, slaughtered or enslaved the inhabitants, and crushed Byzantine armies. In one especially colorful moment in Bulgarian history, the Bulgar Khan, Krum, converted the skull of a slain emperor into a goblet in about 810 CE to toast his victory over a Byzantine army. Fifty years later, however, another Khan, Boris I, converted to Christianity and opened diplomatic relations with Constantinople.

This was an interesting and surprisingly common pattern: many “barbarian” peoples and kingdoms willingly converted to Christianity rather than having Christianity imposed on them through force. The Bulgars were consistently able to defeat Byzantine armies and they occupied territory seized from the Byzantine Empire, yet Boris I chose to convert (and to insist that his followers do as well). The major reason for this deliberate conversion revolved around the desire on the part of barbarian kings to, simply, stop being barbarians. Most kings recognized that Christianity was a prerequisite to entering into trade and diplomatic relations with Byzantium and the Christian kingdoms of the west. Once a kingdom converted, it could consider itself a member of the network of civilized societies, carry out alliances and trade with other kingdoms, and receive official recognition from the emperor (who still wielded considerable prestige and authority, even outside of the areas of direct Byzantine control).

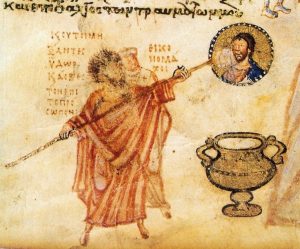

An important figure in the history of eastern Christianity was St. Cyril, who in the ninth century created an alphabet for the Slavic languages, now called Cyrillic and still used in many Slavic languages including Russian. He then translated Greek liturgy into Slavonic and used it to teach and convert the inhabitants of Moravia and Bulgaria. Monasteries sprung up, from which monks would go further into Slavic lands, ultimately tying together a swath of territory deep into what would one day be Russia. The success of these missionary efforts united much of Eastern Europe and Byzantium in a common religious culture – that of Eastern Orthodoxy. Thus, up to the present, the Greek, Russian, Ukrainian, and Serbian Orthodox churches all share common historical roots and a common set of beliefs and practices.

Constantinople and the Emperors

A major factor in the success of Orthodox conversion among the Slavic peoples of Eastern Europe was the splendor of Constantinople itself. Numerous accounts survive of the sheer impact Constantinople’s size, prosperity, and beauty had on visitors. Constantinople was simply the largest, richest, and most glorious city in Europe and the Mediterranean region at the time. It enjoyed a cash economy, impregnable defensive fortifications, and abundant food thanks to the availability of Anatolian grain and fish from the Aegean Sea. Silkworms were smuggled out of China in roughly 550, at which point Constantinople became the heart of a European silk industry, an imperial monopoly which generated tremendous wealth. The entire economy was regulated by the imperial government through a system of guilds, which helped ensure steady tax revenues.

Meanwhile, in the heart of the empire, the emperor held absolute authority. A complex and formal ranking system of nobles and courtiers, clothed in garments dyed specific colors to denote their respective ranks, separated the person of the emperor from supplicants and ambassadors. This was not just self-indulgence on the part of the emperors, of showing off for the sake of feeling important; this was part of the symbolism of power, of reaching out to a largely illiterate population with visible displays of authority.

The imperial bureaucracy held enormous power in Byzantium. Provincial elites would send their sons to Constantinople to study and obtain positions. Bribery was rife and nepotism was as common as talent in gaining positions; there was even an official list of maximum bribes that was published by the government itself. That said, the bureaucracy was somewhat like the ancient Egyptian class of scribes, men who maintained coherence and order within the government. The imperial office controlled the minting of coins, still the standard currency as far away as France and England because the coins were reliably weighted and backed by the imperial government. The emperor’s office also controlled imperial monopolies on key industries like silk, which were hugely lucrative. It was illegal to try to compete with the imperial silk industry, so enormous profits were directed straight into the royal treasury.

Constantinople housed as many as a million people in the late eighth century (as compared to no more than 15,000 in any “city” in western Europe), but there were many other rich cities within its empire. As a whole, Byzantium traded its high-quality finished goods to western Europe in return for raw materials like ore and foodstuffs. Despite its wars with its neighbors to the east and south, Byzantium also had major trade links with the Arab states.

Orthodox Christianity and Learning

To return to Orthodox Christianity, it was not just because Constantinople was at the center of the empire that Byzantines thought it had a special relationship with God. Its power was derived from the sheer number of churches and relics present in the city, which in turn represented an enormous amount of potentia (holy power). Byzantines believed that God oversaw Constantinople and that the Virgin Mary interceded before God on the behalf of the city. Many priests taught that Constantinople was the New Jerusalem that would be at the center of events during the second coming of Christ, rather than the actual Jerusalem.

The piety of the empire sometimes undermined secular learning, however. Over time, the church grew increasingly suspicious of learning that did not either center on the Bible and religious instruction or have direct practical applications in crafts or engineering. Thus, there was a marked decline in scholarship throughout the empire. Eventually, the whole body of ancient Greek learning was concentrated in a small academic elite in Constantinople and a few other important Greek cities. What was later regarded as the founding body of thought of Western Civilization – ancient Greek philosophy and literature – was thus largely analyzed, translated, and recopied outside of Greece itself in the Arab kingdoms of the Middle Ages. Likewise, almost no one in Byzantium understood Latin well by the ninth century, so even Justinian’s law code was almost always referenced in a simplified Greek translation.

This was a period in which, in both the Arab kingdoms and in Byzantium, there was a bewildering mixture of language, place of origin, and religious affiliation. For example, a Christian in Syria, a subject of the Muslim Arab kingdoms by the eighth century, would be unable to speak to a Byzantine Christian, nor would she be welcomed in Constantinople since she was probably a Monophysite Christian (one of the many Christian heresies, at least from the Orthodox perspective) instead of an Orthodox one. Likewise, men in her family might find themselves enlisted to fight against Byzantium despite their Christian faith, with political allegiances outweighing religious ones.

Iconoclasm

One of the greatest religious controversies in the history of Christianity was iconoclasm, the breaking or destroying of icons. Iconoclasm was one of those phenomena that may seem almost ridiculously trivial in historical hindsight, but it had an enormous (and almost entirely negative) impact at the time. For people who believed in the constant intervention of God in the smallest of things, iconoclasm was an enormously important issue.

The conundrum that prompted iconoclasm was simple: if Byzantium was the holiest of states, watched over by the Virgin Mary and ruled by emperors who were the “beloved of God,” why was the empire declining? Just as Rome had fallen in the west, Byzantium was beset by enemies all around it, enemies who had the depressing tendency of crushing Byzantine armies and occasionally murdering its emperors. Byzantine priests repeatedly warned their congregations to repent of their sins, because it was sin that was undermining the empire’s survival. The emperor Leo III, who ruled from 717 – 741, decided to take action into his own hands. He forced communities of Jews in the empire to convert to Christianity, convinced that their presence was somehow angering God. He then went on to do something much more unprecedented than persecuting Jews: attacking icons.

Icons were (and are) one of the central aspects of Eastern Orthodox Christian worship. An icon is an image of a holy figure, almost always Christ, the Virgin Mary, or one of the saints, that is used as a focus of Christian worship both in churches and in homes. Byzantine icons were beautifully crafted and, in a largely illiterate society, were vitally important in the daily experience of most Christians. The problem was that it was a slippery slope from venerating God, Christ, and the saints “through” icons as symbols, versus actually worshiping the icons themselves as idols, something expressly forbidden in the Old Testament. Frankly, there is no question that thousands of believers did treat the icons as idols, as objects with potentia unto themselves, like relics.

In 726, a volcano devastated the island of Santorini in the Aegean sea. Leo III took this as proof that icon veneration had gone too far, as some of his religious advisers had been telling him. He thus ordered the destruction of holy images, facing outright riots when workers tried to make good on his proclamation by removing icons of Christ affixed to the imperial palace. In the provinces, whole regions rose up in revolt when royal servants or “iconoclasts” (image breakers) showed up and tried to destroy icons. In Rome, Pope Gregory II was appalled and excommunicated Leo. Leo, in turn, declared that the pope no longer had any religious authority in the empire, which for practical purposes meant the regions under Byzantine control in Italy, Sicily, and the Balkans.

When Leo III died in 741, his successor, Constantine V, continued the campaign, harshly persecuting idol worshipers. While Leo III allowed Christ to be portrayed in his human form, Constantine V deemed this as circumscribing God’s divine nature and thus heretical. He purportedly even destroyed the largest Christian icon in Constantinople, the golden Christ above the emperor’s own palace gates .Furthermore, Constantine V “held a public scorn” against monastic sects, ordering each monk to hold hands with women and allow themselves to be spat on and insulted by passing individuals at the Hippodrome. He burned other monasteries after pillaging them of their treasures and even stoned some monks to death who refused to conform with the destruction of icons.

The official ban of icons lasted until 843, over a century, before the emperors reversed it (it was an empress, named Theodora like the famous wife of Justinian centuries earlier, who led the charge to officially restore icons). The controversy weakened the empire by dividing it between iconoclasts loyal to the official policy of the emperors and traditionalists who venerated the icons, while the empire itself was still beset by invasions. Iconoclasm also lent itself to what would eventually become a permanent split between the eastern and western churches – Orthodoxy and Catholicism. The final and permanent split between the western and eastern churches, already de facto in place for centuries, was in 1054, when Pope Leo IX and Patriarch Michael I excommunicated each other after Michael refused to acknowledge Leo’s preeminence – this event cemented the “Great Schism” (schism means “break” or “split”) between the western and eastern churches.

In the wake of iconoclasm, the leaders of the Orthodox church, the patriarchs of Constantinople, would claim that innovations in theology or Christian practice were heresies. This attitude extended to secular learning as well – it was acceptable to study classical literature and even philosophy, but new forms of philosophy and scholarly innovation was regarded as dangerous. The long-term pattern was thus that, while it preserved ancient learning, Byzantine intellectual culture did not lend itself to progress.

As the Byzantines turned more and more deeply into their own traditions, more differences emerged between the two versions of Catholicism. Some of these were important, such as the dispute over from whom the Holy Spirit proceeded “from the father” (East) or from “the father and from the Son” (West). Greek monks shaved the front of their heads, whereas Western monks shaved a circlet on the top. The Greek Church used leavened bread with yeast to worship, whereas the Western Church used unleavened bread. Taken together these differences amounted to a sharpening of the divide between Christian groups whom we may now label “Orthodox” and “Roman Catholic”. Neither group wished to see a division in the church, but physical separation and independent cultural evolution ultimately produced two different religious traditions.

With its new geographic shape and its Orthodox faith, Byzantium was at once something old and something new. In official Byzantine ideology, the Roman Empire was and always had been one and inseparable. It is interesting to ask how familiar Augustus Caesar would have found the empire of Constantine V in the 8th century. With its indebtedness to classical and Christian traditions, there can be no question that Byzantium was a part of the West. But in its comparatively modest size, its constantly threatened frontiers, and its Orthodox traditions, Byzantium faced quite a different future than the portions of Rome’s former western provinces.

Catholic Kingdoms of the West

The Papacy

The Latin Church was distinguished by the at least nominal leadership of the papacy based in Rome – indeed, it was the papal claim to leadership of the Christian Church as a whole that drove a permanent wedge between the western and eastern churches, since the Byzantine emperors claimed authority over both church and state. The popes were not just at the apex of the western church, they often ruled as kings unto themselves, and they always had complex relationships with other rulers. For the entire period of the early Middle Ages (from the end of the western Roman Empire until the eleventh century), the popes were rarely acknowledged as the sovereigns of the Church outside of Italy. Instead, this period was important in the longer history of institutional Christianity because many popes at least claimed authority over doctrine and organization – centuries later, popes would look back on the claims of their predecessors as “proof” that the papacy had always been in charge.

An important example of an early pope who created such a precedent is Gregory the Great, who was pope at the turn of the seventh century. Gregory still considered Rome part of the Byzantine Empire, but by that time Byzantium could not afford troops to help defend the city of Rome, and he was keenly interested in developing papal independence. As a result, Gregory shrewdly played different Germanic kings against each other and used his spiritual authority to gain their trust and support. He sent missionaries into the lands outside of the kingdoms to spread Christianity, both out of a genuine desire to save souls and a pragmatic desire to see wider influence for the Church.

Gregory’s authority was not based on military power, nor did most Christians at the time assume that the pope of Rome (all bishops were then called “pope,” meaning simply “father”) was the spiritual head of the entire Church. Instead, popes like Gregory slowly but surely asserted their authority by creating mutually-beneficial relationships with kings and by overseeing the expansion of Christian missionary work. In the eighth century, the papacy produced a (forged, as it turned out) document known as the Donation of Constantine in which the Roman emperor Constantine supposedly granted authority over the western Roman Empire to the pope of Rome; that document was often cited by popes over the next several centuries as “proof” of their authority. Nevertheless, even powerful and assertive popes had to be realistic about the limits of their power, with many popes being deposed or even murdered in the midst of political turmoil.

Excerpt of the “Donation of Constantine”

We ordain and decree that [the pope] shall have the supremacy as well over the four chief seats Antioch, Alexandria, Constantinople, and Jerusalem, as also over all the churches of God in the whole world. And he who for the time being shall be pontiff of that holy Roman Church shall be more exalted than, and chief over, all the priests of the whole world and, according to his judgment, everything which is to be provided for the service of God or the stability of the faith of the Christians is to be administered.

And we decree, as to those most reverend men, the clergy who serve, in different orders, that same holy Roman Church, that they shall have the same advantage, distinction, power and excellence by the glory of which our most illustrious senate is adorned; that is, that they shall be made patricians and consuls, we commanding that they shall also be decorated with the other imperial dignities. And even as the imperial soldiery, so, we decree, shall the clergy of the holy Roman church be adorned.

We also decreed this, that this same venerable one our father Sylvester, the supreme pontiff, and all the pontiffs his successors, might use and bear upon their heads, to the Praise of God and for the honor of St. Peter, the diadem – that is, the crown which we have granted him from our own head, of purest gold and precious gems. But he, the most holy pope, did not at all allow that crown of gold to be used over the clerical crown which he wears to the glory of St. Peter; but we placed upon his most holy head, with our own hands, a tiara of gleaming splendor representing the glorious resurrection of our Lord. And, holding the bridle of his horse, out of reverence for St. Peter, we performed for him the duty of groom; decreeing that all the pontiffs his successors, and they alone, may use that tiara in processions.

In imitation of our own power, in order that for that cause the supreme pontificate may not deteriorate, but may rather be adorned with power and glory even more than is the dignity of an earthly rule, behold we giving over to the oft-mentioned most blessed pontiff, our father Sylvester the universal pope, as well our palace, as has been said, as also the city of Rome and all the provinces, districts and cities of Italy or of the western regions; and relinquishing them, by our inviolable gift, to the power and sway of himself or the pontiffs his successors-do decree, by this our godlike charter and imperial constitution, that it shall be so arranged; and do concede that they (the palaces, provinces etc.) shall lawfully remain with the holy Roman Church. (Donation, 5-6)

Source: https://www.worldhistory.org/Donation_of_Constantine/

Thus, Christianity spread not because of an all-powerful, highly centralized institution, but because of the flexibility and pragmatism of missionaries and the support of secular rulers (the Franks, considered below, were critical in this regard). All across Europe, missionaries had official instructions not to battle pagan religious practice, but to subtly reshape it. It was less important that pagans understood the nuances of Christianity and more important that they accepted its essential truth. All manner of “pagan” practices, words, and traditions survive into the present thanks to the crossover between Christianity and old pagan practices, including the names of the days of the week in English (Wednesday is Odin’s, or Wotan’s, day, Thursday is Thor’s day, etc). and the word “Easter” itself, from the Norse goddess of spring and fertility named Eostre.

As an example, in a letter to one of the major early English Christian leaders (later a saint), Bede, Pope Gregory advised Bede and his followers not to tear down pagan temples, but to consecrate and reuse them. Likewise, the existing pagan days of sacrifice were to be rededicated to God and the saints. Clearly, the priority was not an attempted purge of pagan culture, but instead the introduction of Christianity in a way that could more easily truly take root. Monks sometimes squabbled about the nuances of worship, but the key development was simply the spread of Christianity and the growing influence of the Church.

Characteristics of Medieval Christianity

The fundamental belief of medieval Christians was that the Church as an institution was the only path to spiritual salvation. It was much less important that a Christian understand any of the details of Christian theology than it was that they participate in Christian worship and, most importantly, receive the sacraments administered by the clergy. Given that the immense majority of the population was completely illiterate, it was impossible for most Christians to have access to anything but the rudiments of Christian belief. The path to salvation was thus not knowing anything about the life of Christ, the characteristics of God, or the names of the apostles, but of two things above all else: the sacraments and the relevant saints to pray to.

The sacraments were, and remain in contemporary Catholicism, the essential spiritual rituals conducted by ordained priests. Much of the practical, day-to-day power and influence exercised by the Church was based on the fact that only priests could administer the sacraments, making access to the Church a prerequisite for any chance of spiritual salvation in the minds of medieval Christians. The sacraments are:

- Baptism – believed to be necessary to purge original sin from a newborn child. Without baptism, medieval Christians believed, even a newborn who died would be denied entrance to heaven. Thus, most people tried to have their newborns baptized immediately after birth, since infant mortality was extremely high.

- Communion – following the example of Christ at the last supper, the ritual by which medieval Christians connected spiritually with God. One significant element of this was the belief in transubstantiation: the idea that the wine and holy wafer literally transformed into the blood and body of Christ at the moment of consumption.

- Confession – necessary to receive forgiveness for sins, which every human constantly committed.

- Confirmation – the pledge to be a faithful member of the Church taken in young adulthood.

- Marriage – believed to be sanctified by God.

- Holy orders – the vows taken by new members of the clergy.

- Last Rites – a final ritual carried out at the moment of death to send the soul on to purgatory – the spiritual realm between earth and heaven where the soul’s sins would be burned away over years of atonement and purification.

Unlike in most forms of contemporary Christianity, which tend to focus on the relationship of the individual to God directly, medieval Christians did not usually feel worthy of direct contact with the divine. Instead, the saints were hugely important to medieval Christians because they were both holy and yet still human. Unlike the omnipotent and remote figure of God, medieval Christians saw the saints as beings who cared for individual people and communities and who would potentially intercede on behalf of their supplicants. Thus, every village, every town, every city, and every kingdom had a patron saint who was believed to advocate on its behalf.

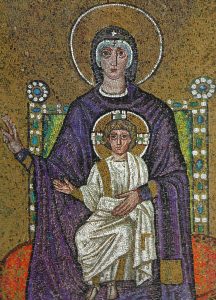

Along with the patron saints, the figures of Jesus and Mary became much more important during this period. Saints had served as intermediaries before an almighty and remote deity in the Middle Ages, but the high Church officials tried to advance veneration of Christ and Mary as equally universal but less overwhelming divine figures. Mary in particular represented a positive image of women that had never existed before in Christianity. The growing importance of Mary within Christian practice led to a new focus on charity within the Church, since she was believed to intervene on behalf of supplicants without need of reward.

Visigothic Spain

After their defeat by the Franks in 507 CE and move to Spain, the Visigoths came close to unifying all of the Iberian Peninsula and converted form Arianism to Roman Catholicism. The conversion of the Visigoths permitted close cooperation between the church and the monarchy and placed the resources of the church at the disposal of the king as he attempted to unite and govern the country. The career of Archbishop Isidore of Seville (560-636) is a prime indicator of those resources. He came from an old Hispano-Roman family, received a fine education, and wrote histories, biblical commentaries, and a learned encyclopedia. By the mid-seventh century economic prosperity, a high degree of assimilation between Goths and Hispano-Romans, and a brilliant culture marked the high point of Visigothic Spain.

Then in 711, Muslims from North Africa invaded Spain. Within five years Berbers (native North Africans and recent converts to Islam who were led by Arabs) completed the conquest of much of the Iberian Peninsula, except for the very northwest of the territory. In 722, when the Visigoths led by King Pelayo were able to stop the Moors from further northward progress in the Battle of Covadonga, and continued for 781 years. Slowly, battle by battle and village after village, the “Spaniards” were able to wrest the Iberian Peninsula from the hands of the Moors. To this day you can still see the impact of Moorish architecture on the parts of the Spain that they occupied.

Meanwhile, in 716 the caliph at Damascus introduced an emir who ruled from Cordoba. The emirate of Cordoba struggled to make good its authority over all of Spain but failed to do so. Christians in the rugged mountains of the northwest-the region called Asturias-could not be dislodged, and the Muslims part of Spain-known as al-Andalus-was plagued by the same divisions as the Islamic East: Arab factions against other Arab factions, Arabs against non-Arab Muslims, and Muslims against non-Muslims. Secure than in mountainous Asturias, Christian kings built a capital at Oveido and in the 9th century launched attacks against al-Andalus, beginning the six hundred year conflict known as the Reconquista pitting Christians and Muslims against one another for control of the Iberian Peninsula. We will discuss this more when we look at the Crusades in the next chapter.

Anglo-Saxon England

Britain was less thoroughly Romanized and thus more quickly given up by the Romans. Already by about 400 CE, the Romans abandoned Britain. Their legions were needed to help defend the Roman heartland and Britain had always been an imperial frontier, with too few Romans to completely settle and “civilize” the territory. For the next three hundred tears, Germanic invaders called the Anglo-Saxons from the areas around present-day northern Germany and Denmark invaded, raided, and settled England. They fought the native Britons (i.e. the Romanized, Christian Celts native to England itself), the Cornish, the Welsh, and each other. Those Romans who had settled in England were pushed out, either fleeing to take refuge in Wales or across the channel to Brittany in northern France. England was thus the most thoroughly de-Romanized of the old Roman provinces in the west: Roman culture all but vanished, and thus English history “began” as that of the Anglo-Saxons.

England’s one clear and deep connection to western Europe was Christianity and/or the Roman Catholic Church. Around 600 the small Anglo-Saxon kingdoms created in the 6th century took the first steps toward converting to Christianity, and joining England inseparably to the European World. The period between 600 and 900 saw only the faint beginnings of consolidation in the Celtic realms (the Celts being Britain’s inhabitants before the Romans invaded in the first century), where the development of the Catholic Church preceded large-scale political organization. In 597 Pope Gregory I sent a small band of missionaries under a Roman monk named Augustine to King Aethelbert of Kent, whose Christian wife, Bertha, had prepared the ground for the newcomers. From their base of operations at Canterbury in southeastern England, Augustine and his successors had limited success spreading Christianity, but a new field of influence was opened to them when Aethelbert’s daughter married a king of North Umbria and took missionaries to their new home. Slowly Christianity spread across the island, but it did so without a uniform design or plan.

So, in 668 the pope sent a new archbishop to England, Theodore, based out of Canterbury. He was a Syrian monk who travelled widely in the East, lived for a time in Rome, gained great experience in church administration, and acquired a reputation for both learning and discretion. The church in England was in an administrative shambles. Working tirelessly, Theodore built up a typical Roman ecclesiastical structure, introduced authoritative Roman canon law for the church, and promoted Christian education opening the first school in Canterbury. Theodore laid the foundations for a unified English church that contributed to the eventual political unification of England.

Starting in the late eighth century, the Anglo-Saxons suffered waves of Viking raids (more on the Vikings later in the chapter) that culminated in the establishment of an actual Viking kingdom in what had been Anglo-Saxon territory in eastern England. It took until 879 for the surviving English kingdom, Wessex, to defeat the Viking invaders. For a few hundred years, there was an Anglo-Saxon kingdom in England that promoted learning and culture, producing an extensive literature in Old English (the best preserved example of which is the epic poem Beowulf). Raids started up again, however, and in 1066 William the Conqueror, a Viking-descended king from Normandy in northern France, invaded and defeated the Anglo-Saxon king and instituted Norman rule.

The Franks

The Franks created the most effective of the early Germanic kingdoms and were one of the first Germanic Kingdoms to convert to mainstream Roman Catholicism in the early 6th century. The former Roman province of Gaul is the heartland of present-day France, ruled in the aftermath of the fall of Rome by the Franks, a powerful Germanic people who invaded Gaul from across the Rhine as Roman power crumbled. The Franks were a warlike and crafty group led by a clan known as the Merovingians. A Merovingian king, Clovis (r. 481 – 511) was the first to unite the Franks and begin the process of creating a lasting kingdom named after them: France. Clovis murdered both the heads of other clans who threatened him as well as his own family members who might take over command of the Merovingians. He then expanded his territories and defeated the last remnants of Roman power in Gaul by the end of the fifth century.

The Merovingian Dynasty

In 500 CE Clovis and a few thousand of his most elite warriors converted to Latin Christianity, less out of a heartfelt sense of piety than for practical reasons: he planned to attack the Visigoths of Spain, Arian Christians. By converting to Latin Christianity, Clovis ensured that the subjects of the Goths were likely to welcome him as a liberator rather than a foreign invader. He was proved right, and by 507 the Franks controlled almost all of Gaul, including formerly-Gothic territories along the border. The Visigoths were then pushed westward to Iberia.

It is through conquest that historians gain insight into Frankish religion. Clovis often utilized marriage to solidify military alliances with foreign powers. However, on Christmas Day in 496, 498, or 506 (records conflict on the actual year), Clovis I converted to Catholicism. Contemporary historian Gregory of Tours argues that it was Clovis’ wife, Clothild, who urged conversion; however, it was not until his confrontation with the Alemanni at Tolbac that he vowed to convert upon victory. Clovis’ conversion promoted the spread of Christianity within his followers, as religion intensely intertwined with societal and militaristic campaigns.

While Clovis’ conversion to Christianity vastly influenced the Merovingian people, Clothild and subsequent queens prompted significant religious change. Known for her devout Christian faith, Queen Clothild built numerous churches and monasteries and was considered extremely charitable. This tradition continued with Queen Radegund (520-587 AD), who married Clothar I, son of Clovis and Clothild, in 532 AD. In the autobiographical account of her life, The Life of the Holy Radegund, author Venantius Fortunatus described Queen Radegund as a generous partner to God. Fortunatus further described her as charitable, donating to monasteries and the poor before establishing a nunnery in Athies. Despite the pagan past of the Merovingian kings, these queens aided in the transition of an empire.

Between 500 and 511, Clovis I issued the Salic Law and Pactus Legis Salicae. While the Salic Law mostly limited the succession to male heirs, Pactus’ sixty-five chapters outlined simplistic, secular law with a minor Christian influence directed to the entirety of the Frankish kingdom. This showcased a direct Roman influence on the Merovingian Kingdom, as the transcription of law was not commonly practiced in Germanic communities. By expanding his territory, converting to Christianity, and codifying law, Clovis I ultimately united the tribal Franks into the Frankish Kingdom. While the Carolingians would later overthrow the Merovingian Dynasty, their legacy remains one of Western Europe’s most powerful kingdoms.

The Carolingian Dynasty

The Merovingians held on to power for two hundred years. In the end, they became relatively weak and ineffectual, with another clan, the Carolingians, running most of their political affairs. Only the first few kings in the Merovingian dynasty of the Franks were particularly smart or capable. Throughout the 7th century the Carolingians gained power and prominence by forming alliances with powerful noble families as well as waging war against their enemies, eventually using ware to expand the territorial integrity of their kingdom. It was a Carolingian, Charles Martel, who defeated the invading Arab armies at the Battle of Tours (also referred to as the Battle of Poitiers) in 732. Soon afterwards, Charles Martel’s son Pippin seized power from the Merovingians in a coup, one later ratified by the pope in Rome, ensuring the legitimacy of the shift and establishing the Carolingians as the rightful rulers of the Frankish kingdom.

When Pippin seized control in 750 CE, he was merely assuming the legal status that his clan had already controlled behind the scenes for years. With booty from their wars, tribute from conquered peoples, and even lands seized from the church, the Carolingians attracted and rewarded more and more followers until no one was a match for them in Western Europe. The Carolingians also allied themselves very early with the leading churchmen, both regular and monastic. They aided missionaries in the work of converting central Europe, thereby expanding Frankish influence in that area. Then in 751, the Frankish leader Pippin III (son of Martel) made a formal alliance with the pope to achieve their own ends to be recognized as absolute King of all the Frankish territories. In exchange the Franks promised to protect the Papal States from any intruders. This was a huge shift, no longer would Rome and the Pope look east to Byzantium for help, but West to Europe.

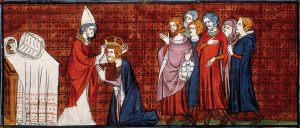

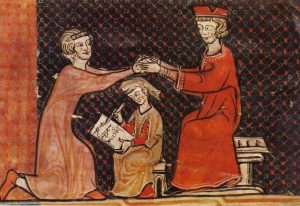

Three years later when the pope visited the Frankish kingdom, he crowned and anointed Pippin III and his sons, including Charlemagne. The practice of anointing the head of a ruler with holy oil, which renders the recipient sacred dates back to the kings of Israel. The head and hands of Catholic bishops also were anointed. The anointing of rulers and churchmen persisted throughout the Middle Ages and into the Modern World until the end of Absolute monarchs in the 20th century. The pope also forbade the Franks ever to choose a king from a family other than the Carolingians.

The problem facing the Franks was that Frankish tradition stipulated that lands were to be divided between sons after the death of the father. Thus, with every generation, a family’s holdings could be split into separate, smaller pieces. Over time, this could reduce a large and powerful territory into a large number of small, weak ones. When Pepin died in 768, his sons Charlemagne and Carloman each inherited half of the kingdom. When Carloman died a few years later, however, Charlemagne ignored the right of Carloman’s sons to inherit his land and seized it all (his nephews were subsequently murdered).

The Carolingian Empire reached its height under Charlemagne, 768-814. Charlemagne or “Charles the Great” was a complex and somewhat contradictory character. He was well learned in some ways (spoke and read Frankish, Latin, and some Greek), but never learned to write. He promoted Christian morality but perpetuated unspeakable brutalities on his enemies and enjoyed several concubines. Many battles were fought in his name, but he rarely accompanied his armies and fought no campaigns that are remembered for strategic brilliance. Determination and organization were the hallmarks of his 46 year reign. And perhaps most importantly was how he viewed the link between executive and religious power.

Charlemagne was one of the most important kings in medieval European history. Charlemagne waged constant wars during his long reign (lasting over 40 years) in the name of converting non-Christian Germans to his east and, equally, in the name of seizing loot for his followers. From his conquests arose the concept of the Holy Roman Empire, a huge state that was nominally controlled by a single powerful emperor directly tied to the pope’s authority in Rome. In truth, only under Charlemagne was the Empire a truly united state, but the concept (with various emperors exercising at least some degree of authority) survived until 1806 when it was finally permanently dismantled by Napoleon. Thus, like the western Roman Empire that it succeeded, the Holy Roman Empire lasted almost exactly 1,000 years.

Charlemagne distinguished himself not just by the extent of the territories that he conquered, but by his insistence that he rule those territories as the new, rightful king. In 773, at the request of the pope, Charlemagne invaded the northern Italian kingdom of the Lombards, the Germanic tribe that had expelled Byzantine forces earlier. When Charlemagne conquered them a year later, he declared himself king of the Lombards, rather than forcing a new Lombard ruler to become a vassal and pay tribute. This was an unprecedented development: it was untraditional for a Germanic ruler to proclaim himself king of a different people – how could Charlemagne be “king of the Lombards,” since the Lombards were a separate clan and kingdom? This bold move on Charlemagne’s part established the answer as well as an important precedent (inspired by Pepin’s takeover): a kingship could pass to a different clan or even kingdom itself depending on the political circumstances. Charlemagne was up to something entirely new, intending to create an empire of various different Germanic groups, with himself (and by extension, the Franks) ruling over all of them.

Charlemagne based his right to rule over both the Franks and others within a religious framework. Not only did he, as well as his ancestors and those who would inherit his throne, believe his position came from the authority of the pope, but from God himself. Charlemagne firmly believed that as God was the sole legitimate ruler in heaven, he was the sole legitimate ruler on earth and had been divinely appointed. In other words Charlemagne believed that God had chosen him as King and it was directly from God that he received his authority. To Charlemagne, as to most Byzantine and Muslim rulers, no boundary existed between the church and the state. Church (or religion) and state were complementary attributes of a polity whose end was securing personal salvation. Charlemagne’s ideological legacy was twofold. On the one hand, it created the origins of the bitter struggles later in the Middle Ages between secular rulers and ecclesiastical powers about the leadership of Christian society. On the other hand, it made it hard to define the state and its essential purposes in other than religious terms, a legacy lasting until the 18th century for most western Europe.

This leads us to the most disputed event in Charlemagne’s reign, his imperial coronation in Rome on Christmas in 800 when pope Leo III crowned him as the Holy Roman Emperor. So how did Charlemagne come to be crowned as Emperor by the pope? The saga began in April 799 when some disgruntled papal bureaucrats and their supporters attacked Pope Leo III in an attempt to depose him, accusing him of perjury, adultery and threatening to blind him and cut his tongue out. Leo was saved by an ally of Charlemagne and then traveled all the way to Saxony, where the king was camped with his army. Charlemagne agreed to restore the pope to Rome and, as his ally and protector, to investigate those who had attacked him. Supposedly, no real offenses could be proved against the pope, who with Charlemagne appeared publicly in Rome to swear that all accusations were false. When Charlemagne went to Saint Peter’s Basilica on Christmas Day, he prayed before the main altar and as he rose from prayer, Pope Leo III placed a crown on his head and the assembled Romans acclaimed him as emperor.

While Charlemagne’s biographers claimed that this came as a surprise to Charlemagne, it was anything but; Charlemagne completely dominated Leo and looked to use the prestige of the imperial title to cement his hold on power. Charlemagne had already restored Leo to his throne after Leo was run out of Rome by powerful Roman families who detested him. While visiting Italy (which was now part of his empire), Charlemagne was crowned and declared to be the emperor of Rome, a title that no one had held since the western empire fell in 476. Making the situation all the stranger was the fact that the Byzantine emperors considered themselves to be fully “Roman” – from their perspective, Leo’s crowning of Charlemagne was a straightforward usurpation.

While some have taken this to mean that Charlemagne was the Emperor of Rome, he likely did not. He did believe that he was the Emperor of the Frankish kingdom, and protector of Rome, but not the leader of the city. His polices, priorities, and residence did not change after the coronation. He returned home to Saxony and continued fighting as needed to maintain and grow his empire. And it was a sizable empire, encompassing most of what we consider to be Western Europe today.

Despite, his lofty aspirations of leading Rome or the Roman Empire, Charlemagne’s empire was a poor reflection of ancient Rome. He had almost no bureaucracy, no standing army, not even an official currency. He spent almost all of his reign traveling around his empire with his armies, both leading wars and issuing decrees. He did insist, eventually, that these decrees be written down, and the form of “code” used to ensure their authenticity was simply that they were written in grammatically correct Latin, something that almost no one outside of Charlemagne’s court (and some members of the Church scattered across Europe) could accomplish thanks to the abysmal state of education and literacy at the time.

Charlemagne organized his empire into counties, ruled by (appropriately enough) counts, usually his military followers but sometimes commoners, all of whom were sent to rule lands they did not have any personal ties to. He protected his borders with marches, lands ruled by margraves who were military leaders ordered to defend the empire from foreign invasion. He established a group of officials who traveled across the empire inspecting the counties and marches to ensure loyalty to the crown. Despite all of his efforts, rebellions against his rule were frequent and Charlemagne was forced to war against former subjects to re-establish control on several occasions.

Charlemagne also reorganized the Church by insisting on a strict hierarchy of archbishops to supervise bishops who, in turn, supervised priests. Likewise, under Charlemagne there was a revival of interest in ancient writings and in proper Latin. He gathered scholars from all of Europe, including areas like England beyond his political control, and sponsored the education of priests and the creation of libraries. He had flawed versions of the Vulgate (the Latin Bible) corrected and he revived disciplines of classical learning that had fallen into disuse (including rhetoric, logic, and astronomy). His efforts to reform Church training and education are referred to by historians as the “Carolingian Renaissance.”

One innovation of note that arose during the Carolingian Renaissance is that Charlemagne instituted a major reform of handwriting, returning to the Roman practice of large, clear letters that are separated from one another and sentences that used spaces and punctuation, rather than the cursive scrawl of the Merovingian period. This new handwriting introduced the division between upper and lower-case letters and the practice of starting sentences with the former that we use to this day. Carolingian workshops produced over 100,000 manuscripts in the 9th century, of which some 6000 to 7000 survive. The Carolingians produced the earliest surviving copies of the works of Cicero, Horace, Lucretius, and Julius Caesar to name a few.

Despite all of its greatness the Carolingian Empire did not outlive the 9th century. Rome’s empire lasted much longer, as did Byzantium’s and Islam’s. All of these realms were fatally weakened by similar problems, but those problems arose more quickly and acutely in the Carolingian world than elsewhere. By the end of the 9th century small political entities had replaced the unified Carolingian Empire. Size and ethnic complexity contributed to the disintegration of the empire. The empire included many small regions-Saxony, Bavaria, Brittany, and Lombardy, for example- that all had their own resident elites, linguistic traditions, and distinctive cultures, which had existed before the Carolingians came on the scene and persist to this day. The Merovingian and Carolingian periods were basically a unifying intrusion into a history characterized by regional diversity. The Carolingians made heroic efforts to build a common culture and to forge bonds of unity, but the obstacles were impossible to overcome.

And then of course were the issues arising from issues of succession. In 806 Charlemagne divided his empire among his three legitimate sons, but two of them died soon thereafter making Louis the Pious his sole heir when he died in 814. The problem, again, was the Frankish succession law. Without an effective bureaucracy or law code, there was little cohesion to the kingdom, and areas began to split off almost immediately after Charlemagne’s death in 814 despite the presence of an heir. Then upon Louis’s death things became even more complex as he divided the empire into three amongst his sons. The arrangement soon devolved into conflict

After three years of internecine fighting, Louis’s sons singed the Treaty of Verdun, in 843, that divided the empire into 3 realms: the West Frankish, the East Frankish, and the Middle Kingdoms, each ruled by one of the three grandsons of Charlemagne. After fierce battles among the brothers, each appointed 40 members to a study commission that traversed the empire to identify royal properties, fortifications, monasteries, and cathedrals so that an equitable division of these valuable resources could be made. Each brother needed adequate resources to solidify his rule and to attract and hold followers. The lines drawn on the map at Verdun did not last even for a generation.

In addition to internal difficulties and fragmentation, a new wave of attacks and invasions decisively ripped apart the already deteriorating Carolingian empire. In the middle decades of the 9th century, Muslims, Vikings, and Magyars wreaked havoc on the Franks. Based in North Africa and the islands of the western Mediterranean, Muslims attacked Italy and southern France. The Byzantines lost Sicily to raiders from North Africa in 827 and found themselves seriously challenged in southern Italy. In the 840s Muslims raised the city of Rome. These same brigands preyed on trade in the western Mediterranean and even set up camps in the Alps to rob traders passing back and forth over the mountains.

Meanwhile, in the northern most reaches of the Carolingian Empire, along with Britain and Ireland, the Northmen or the Vikings began assaulting the empire. Supposedly, “From the fury of the Northmen, O Lord, deliver us,” was a plaintive cry heard often in 9th century Europe. The Vikings were mainly Danes and Norwegians, seeking booty, glory, and political opportunity. Most Viking bands were formed by leaders who had lost out in the dawning institutional consolidation of the northern world. Some were opportunists who sought to profit from the weakness of Carolingian, Anglo-Saxon, and Irish rule. In the mid-9th century, Vikings began settling and initiated their won state-building activities in Ireland, England, northwestern France (Normandy), and early Russia.

All of these attacks were unpredictable and caused local regions to fall back on their own resources rather than look to the central government. Commerce was disrupted everywhere. Schools, based in ecclesiastical institutions suffered severe decline. The raids were all individually small, but together they amounted to despair and disruption on a massive scale.

But even as the Carolingian Empire itself disintegrated, the idea of Europe as “Christendom” as a single political-cultural entity, persisted. The Latin Christian culture promoted by Carolingian schools and rulers set the tone for intellectual life until the 12th century. Likewise, Carolingian governing structures were inherited and adapted by all of the successor states that emerged in the 9th and 10th centuries. In these respects the Carolingian experience paralleled the Roman, and the Islamic and Byzantine, too. A potent centralized regime disappeared but left a profound imprint on its heirs. For hundreds of years Western civilization would be played out inside the lands that had been Charlemagne’s empire and between those lands and their Byzantine and Muslim neighbors.

Charlemagne’s legacy was great. He brought together the lands that would become France, Germany, the Low Countries, and northern Italy and endowed them with a common ideology, government, and culture. He provided a model that Europeans would look back to for centuries as a kind of golden age. His vast supra-regional and supra-ethnic entity, gradually called “Christendom,” drew deeply on the universalizing ideals of its Roman, Christian, and Jewish antecedents but was, nevertheless, original. With its Roman, Germanic, and Christian foundations, the Carolingian Empire represented the final stage in the evolution of the Roman Empire in the West.

Medieval Politics & Society or the “Dark Ages”

The term “Dark Ages” was coined in the 1330s, at the birth of the Renaissance, by humanist scholars to refer to the early Medieval Period or the early Middle Ages. For those living in the 14th century this was a clearly negative reference, however we know now that the “Dark Ages” were anything but dark. That being said, it was a period of slow to little intellectual, architectural, and artistic development, at least in comparison to the golden ages of Greece and Rome. And what innovations occurred were documented sparsely. There were many reasons for the downturn in intellectual development, and production of historical record, including invasions from new farther flung enemies, disruption in trade, and a turn to more rural lifeways. Yet, pockets of ancient Rome, Greek, or Byzantine culture still remained and prospered, eventually laying the foundation for the European Renaissance in the 14th and 15th centuries.

The Vikings

Until the eighth century, the Scandinavian region was on the periphery of European trade, and Scandinavians (the Norse) themselves did not greatly influence the people of neighboring regions. Scandinavian tribesmen had long traded amber (petrified sap, prized as a precious stone in Rome and, subsequently, throughout the Middle Ages) with both other Germanic tribes and even with the Romans directly during the imperial period. While the details are unclear, what seems to have happened is that sometime around 700 CE the Baltic Sea region became increasingly economically significant. Traders from elsewhere in northern Europe actively sought out Baltic goods like furs, timber, fish, and (as before) amber. This created an ongoing flow of wealth coming into Scandinavia, which in turn led to Norse leaders becoming interested in the sources of that wealth. At the same time, the Norse added sails to their unique sailing vessels, longships. Sailed longships allowed the Norse to travel swiftly across the Baltic, and ultimately across and throughout the waterways of Europe.

The Norse, soon known as Vikings, exploded into the consciousness of other Europeans during the eighth century, attacking unprotected Christian monasteries in the 790s, with the first major raid in 793 and follow-up attacks over the next two years. The Vikings swiftly became the great naval power of Europe at the time. In the early years of the Viking period they tended to strike in small raiding parties, relying on swiftness and stealth to pillage monasteries and settlements. As the decades went on, bands of raiders gave way to full-scale invasion forces, numbering in the hundreds of ships and thousands of warriors. They went in search of riches of all kinds, but especially silver, which was their standard of wealth, and slaves, who were equally lucrative. Unfortunately for the monks of Europe, silver was most often used in sacred objects in monasteries, making the monasteries the favorite targets of Viking raiders. The raids were so sudden and so destructive that Charlemagne himself ordered the construction of fortifications at the mouth of the Seine river and began expanding his naval defenses to try to defend against them.

The word “Viking” was used by the Vikings themselves – it either meant “raider” or was a reference to the Vik region that spanned parts of Norway and Sweden. They were known by various other names by the people they raided, from the Middle East to France: the Franks called them “pagani” or “Northmen,” the Anglo-Saxons “haethene men,” the Arabs “al-Majus” (sorcerers), the Germanic tribes “ascomanni” (shipmen), and the Slavs of what would become Russia the “Rus” or “Varangians” (the latter are described below.) Outside of the lands that would eventually become Russia, the Vikings were universally regarded as a terrifying threat, not least because of their staunch paganism and rapacious treatment of Christians.

At their height, the Vikings fielded huge fleets that raided many of the major cities of early medieval Europe and North Africa. By the late ninth century they were formally organized into a “Great Fleet” based in their kingdom in eastern England (they conquered the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of East Anglia in the 870s). While the precise numbers will never be known, not least because the surviving sources bear a pronounced anti-Viking bias, it is clear that their raids were on scale that dwarfed their earlier efforts. In 844 more than 150 ships sailed up the Garonne River in southern France, plundering settlements along the way. In 845, 800 ships forced the city of Hamburg in northern Germany to pay a huge ransom of silver. In 881, the Great Fleet pillaged across present-day Holland, raiding inland as far as Charlemagne’s capital of Aachen and sacking it. Then, in 885, at least 700 ships sailed up the Seine River and besieged Paris (note that their initial target, a rich monastery, had evacuated with its treasure; the wine cellar was not spared, however). In this attack, they extorted thousands of pounds of silver and gold. Vikings attacked Constantinople at least three times in the ninth and tenth centuries, extracting tribute and concessions in trade, and perhaps most importantly, they came to rule over what would one day become Russia. In the end, the Vikings became increasingly knowledgeable about the places they were raiding, in some cases actually working as mercenaries for kings who hired them to defend against other Vikings.

Starting in roughly 850 CE, the Vikings started to settle in the lands they raided, especially in England, Scotland, the hitherto-uninhabited island of Iceland, and part of France. Outside of Russia, their most important settlement in terms of its historical impact was Normandy in what is today northern France, a kingdom that would go on centuries later to conquer England itself. It was founded in 911 as a land-grant to the Viking king Rollo in order to defend against other Vikings. Likewise, the Vikings settled areas in England that would help shape the English language and literary traditions (for example, though written in the language of the Anglo-Saxons, the famous epic poem Beowulf is about Viking settlers who had recently converted to Christianity). Ultimately, the Vikings became so rich from raiding that they became important figures in medieval trade and commerce, trading goods as far from Scandinavia as Baghdad in the Abbasid Caliphate.

The Vikings were not just raiders, however. They sought to explore and settle in lands that were in some cases completely uninhabited when they arrived, like Iceland. They appear to have been fearless in quite literally going where no one had gone before. Much of their exploration required audacity as well as planning – they were the best navigators of their age, but at times their travels led them to forge into areas completely unknown to Europeans. Vikings were the first Europeans to arrive in North America, with a group of Icelandic Vikings arriving in Newfoundland, in present-day Canada, around the start of the eleventh century. An attempt at colonization failed, however, quite possibly because of a conflict between the Vikings and the Indigenous people they encountered, and the people of the Americas were thus spared the presence of further European colonists for almost five centuries.

In what eventually became Russia, meanwhile, Viking exploration, conquest, and colonization had begun even earlier. The Vikings started traveling down Russian rivers from the Baltic in the mid-eighth century, even before the raiding period began farther west. Their initial motive was trade, not conquest, trading and collecting goods like furs, amber, and honey and transporting them south to both Byzantium and the Abbasid Caliphate. The Vikings were slavers as well, capturing Slavic peoples and selling them in the south. In turn, the Vikings brought a great deal of Byzantine and Abbasid currency to the north, introducing hard cash into the mostly barter-based economies of Northern and Western Europe. Eventually, they settled along their trade routes, often invited to establish order by the native Slavs in cities like Kiev, with the Vikings ultimately forming the earliest nucleus of Russia as a political entity. The very name “Russia” derives from “Rus,” the name of the specific Viking people (originally from Sweden) who settled in the Slavic lands bordering Byzantium.

As the Vikings settled in the lands they had formerly raided and as powerful states emerged in Scandinavia itself, the Vikings ceased being raiders and came to resemble other medieval Europeans. By the mid-tenth century, the kings of the Scandinavian lands began to assert their control and to reign in Viking raids. Conversion to Christianity, becoming very common by 1000, helped end the raiding period as well. Denmark became a stable kingdom under its king Harald Bluetooth in 958, Norway in 995 under Olaf Tryggvason, and Sweden in 995 as well under Olof Skötkonung. Meanwhile, in northern France, the kingdom of Normandy emerged as the most powerful of the former Viking states, with its duke William the Conqueror conquering England itself from the Anglo-Saxons in 1066.

The Orders of Medieval Society

While most Europeans (excluding the Jewish communities, the few remaining pagans, and members of heretical groups) may have come to share a religious identity by the eleventh century, Europe was fragmented politically. The numerous Germanic tribes that had dismantled the western Roman Empire formed the nucleus of the early political units of western Christendom. The Germanic peoples themselves had started as minorities, ruling over formerly Roman subjects. They tended to inherit Roman bureaucracy and rely on its officials and laws when ruling their subjects, but they also had their own traditions of Germanic law based on clan membership.

The so-called “feudal” system of law was one based on codes of honor and reciprocity. In the original Germanic system, each person was tied to his or her clan above all else, and an attack on an individual immediately became an issue for the entire clan. Any dishonor had to be answered by an equivalent dishonor, most often meeting insult with violence. Likewise, rulership was tied closely to clan membership, with each king being the head of the most powerful clan rather than an elected official or even necessarily a hereditary monarchy that transcended clan lines. This unregulated, traditional, and violence-based system of “law,” from which the modern English word “feud” derives, stood in contrast to the written codes of Roman law that still survived in the aftermath of the fall of Rome itself.

Over time, the Germanic rulers mixed with their subjects to the point that distinctions between them were nonexistent. Likewise, Roman law faded away to be replaced with traditions of feudal law and a very complex web of rights and privileges that were granted to groups within society by rulers (to help ensure the loyalty of their subjects). Thus, clan loyalty became less important over the centuries than did the rights, privileges, and pledges of loyalty offered and held by different social categories: peasants, townsfolk, warriors, and members of the church. In the process, medieval politics evolved over time into a hierarchical, class-based structure in which kings, lords, and priests ruled over the vast majority of the population: peasants.

Eventually, the relationship between lords and kings was formalized in a system of mutual protection. A lord accepted pledges of loyalty, called a pledge of fealty, from other free men called his vassals; in return for their support in war he offered them protection and land-grants called fiefs. Each vassal had the right to extract wealth from his land, meaning the peasants who lived there, so that he could afford horses, armor, and weapons. In general, vassals did not have to pay their lords taxes (all tax revenue came from the peasants). Likewise, the Church itself was an enormously wealthy and powerful landowner, and church holdings were almost always tax-exempt; bishops were often lords of their own lands, and every king worked closely with the Church’s leadership in his kingdom.

This system arose because of the absence of other, more effective forms of government and the constant threat of violence posed by raiders. The system was never as neat and tidy as it sounds on paper; many vassals were lords of their own vassals, with the king simply being the highest lord. In turn, the problem for royal authority was that many kings had “vassals” who had more land, wealth, and power than they did; it was very possible, even easy, for powerful nobles to make war against their king if they chose to do so. It would take centuries before the monarchs of Europe consolidated enough wealth and power to dominate their nobles, and it certainly did not happen during the Middle Ages.

One (amusing, in historical hindsight) method that kings would use to punish unruly vassals was simply visiting them and eating them out of house and home – the traditions of hospitality required vassals to welcome, feed, and entertain their king for as long as he felt like staying. Kings and queens expected respect and deference, but conspicuously absent was any appeal to what was later called the “Divine Right” of monarchs to rule. From the perspective of the noble and clerical classes at the time the monarch had to hold on to power through force of arms and personal charisma, not empty claims about being on the throne because of God’s will.

Unsurprisingly, there are many instances in medieval European history in which a powerful lord simply usurped the throne, defeated the former king’s forces, and became the new king. Ultimately, medieval politics represented a “warlord” system of political organization, in many cases barely a step above anarchy. Pledges of loyalty between lords and vassals served as the only assurance of stability, and those pledges were violated countless times throughout the period. The Church tried to encourage lords to live in accordance with Christian virtue, but the fact of the matter was that it was the nobility’s vocation, their very social role, to fight, and thus all too often “politics” was synonymous with “armed struggle” during the Middle Ages.

Emergence of Local Rule

But the Medieval Europe that the Vikings entered was not the Ancient world. It was not urban, expect for the larger cities of Byzantium (Constantinople) and the Arab Empire (like Cordoba with 400,000 inhabitants and Baghdad with over 1 million residents). Instead the medieval world was a rural one. Fewer people lived in large towns and city life played a much less important role for the majority of people. Fewer government functions were based in towns, cultural life was less bound to the urban environment, and trade in luxuries, which depend on towns declined. During medieval times trade and exchanges were much more local, with most major trading centers remaining in the East, collecting Asian luxury goods at Byzantium and sending them out into the Mediterranean. Common trade goods, like food and other bulk goods never travelled very far to begin with because the cost was prohibitive. Most towns were supplied with foodstuffs by their immediate hinterlands, so the goods that travel long distances had to be portable and valuable like silks or spices or ivories. Byzantium controlled this luxury trade.

But, while towns in the west lost Roman governmental and economic significance they did often survive as focal points of ecclesiastical administration. A cathedral church required a large corps of administrators. Western towns and churches began attracting burgs, or new settlements of merchants most outside of the actual center. Partially this was for safety. Vikings frequently raided these burgs, their existence than was precarious. Few of these towns were impressive in size, population, or military presence, so they were vulnerable to attacks by violent raiders. Even Rome only had about 30,000 inhabitants in 800, down from over a million when Augustus reigned.

Thus agriculture remained the most important element in medieval Europe’s economy and in the daily lives of most people. And within this rural society, one key institution developed, first in the Frankish West called the manor or a bipartite estate. On the estate one part of the land was set aside as a reserve, or a demesne, and the rest was divided into tenancies. The reserve, consuming from one-quarter to one-half of the total territory of the estate, was exploited directly for the benefit of the landlord. The tenancies were generally worked by the peasants for their own support. The bipartite estate provided the aristocrats with a livelihood while freeing them for military and governmental service.

Estates were run in different ways. A landlord might hire laborers to farm his reserve, paying them with money exacted as fees from his tenants. Or he might require the tenants to work a certain number of days per week or weeks per year in his fields. The produce of the estate might be gathered into barns and consumed locally or hauled to local markets. The reserve might be a separate part of the estate, a proportion of common fields, or a percentage of the harvest. The tenants might have individual farms or work in common fields. Although the manor is one of the most familiar aspects of European life throughout the Middle Ages, large estates with dependent tenants also were evolving in the Byzantine and Islamic worlds. The manor would be the central focus of the very local and stratified society of the medieval west. Outside of the manor, medieval society was divided into three traditional sectors or orders of society. As Alfred the Great of England said once that every kingdom needed “men of prayer, men of war, and men of work.” This three way division reveals the way the elite looked at the world. It provided neat places for the clergy, warrior-aristocrats, and peasants. The clergy and the nobility agreed that they were superior to the “workers” but fierce controversies raged over whether ultimate leadership in society belonged to the “prayers” or the “fighters.” And this tripartite society obviously left a lot of people out including townspeople, workers who were not farmers, women, and Jews. We will see the controversies developing from all these issues shortly.

“Those who Pray”

As the church promoted its own vision of the tripartite ordering of society, it assigned primacy to the prayers-its own leaders. Within the clergy, however, sharp disagreements arose over whether the leading prayers were the monks in the monasteries or the bishops in their cathedrals. Whereas in the Carolingian world the clergy served occasionally as an avenue of upward social mobility for talented outsiders, in the High Middle Ages church offices were usually reserved for the younger sons of the nobility. The church was always hierarchical in organization and outlook, so the increasingly aristocratic character of the church’s leadership tended to reinforce those old tendencies.

Basically then in most towns churches were controlled by the local prince or noble, so there was no separation of religious and secular leadership, like with Charlemagne. Nobles would choose the clergy, usually a son of a Lord would serve as the abbot or head of the local monastery as a result. Often this was the role chosen for the second born son. And as marriage was still legal for priests and monks, it was in many ways just like another job for the nobility, who often did not take their responsibility all that seriously. And even if the church was led by someone other than local noble, Lords and other nobility would simply secure their salvation throughout donations to the church. At least this is what they believed.

As a result of this and in the aftermath of the Carolingian collapse, a great spiritual reform swept Europe seeking to remove the corrupting influence of secular nobility from the church. It began in 910 when Duke William of Aquitaine founded the monastery of Cluny in Burgundy on land that he donated. At a time when powerful local families dominated almost all monasteries, Cluny was a rarity because it was free of all lay and episcopal control and because it was under the direct authority of the pope. Cluny’s abbots were among the greatest European statesmen of their day and became influential advisers to popes, French kings, German emperors, and aristocratic families.

Cluny sought a rededication to original monastic values, especially on prayer. The monks spent long hours in solemn devotions and did little manual work. Because Cluniac prayer was thought to be especially efficacious, nobles all over Europe donated land to Cluny and placed local monasteries under Cluniac control. Many independent monasteries also appealed to Cluny for spiritual reform. By the 12th century hundreds of monasteries had joined in a Cluniac order. Individual houses were under the authority of the abbot of Cluny, and their priors had to attend an annual assembly. Although the majority of houses reformed by Cluny were male, many convents of nuns also adopted Cluniac practices.

Cluny promoted 2 powerful ideas. One was that the role of the church was to pray from the world, not to be implicated deeply in it. So the church, and especially its leaders should remain separate from secular practices and politics. The other was that freedom from lay control was essential if churches were to concentrate on their spiritual tasks. Followers and believers of Cluniac traditions and ideas condemned all clerical immorality and inappropriate lay interference in the church. They preached against clerical marriage and simony, the buying and selling of church offices.