8 Chapter 8: The Dawn of the Roman Empire

By the end of the Third Punic War the Roman Republic had nearly complete control of the Mediterranean, bringing Rome untold wealth and power. However, the expansion was a double edged sword as it brought many unintended and unexpected consequences. Most significantly, expansion exacerbated Rome’s already unequal society, leading the poor to become poorer and the rich to become wealthier. On top of the widening socio-economic gap, many of the newly wealthy legionnaires lacked access to political power, which was still largely dominated by a few Roman families. Here we see a situation similar to those that ended with democratic revolutions in Ancient Greece, first pushed by the Hoplites and later by the rowers. In the end while expansion of the republic brought wealth and fame to many, it ultimately destabilized the regime and led to the transformation of the republic to an empire.

Socioeconomic Consequences of Expansion

For some the expansion of the Roman Republic was nothing short of a blessing. Already wealthy, the Roman elite came into fabulous riches in the wake of the Punic wars and Greek conflicts. Huge profits awaited the generals, patrons, diplomats, magistrates, tax collectors, and businessmen who followed Rome’s armies. In Italy most profits were in the form of land; while in the further afield provinces wealth was found not only in land, but also in slaves, booty, and grafting off the top of any taxes collected. It was common for provincial governors to skim some off the top of all taxes or tribute collected, and while Rome did see this as a problem, it was difficult to stop from afar. The first Roman coinage, dating to 289 BCE facilitated the growth of wealth and commercial transactions, especially important as the republic expanded. Previously, the Romans had made do with barter and/or cast bronze bars, but trade was revolutionized with the adoption of coins (in the style of the Greeks/Hellenistic Kingdoms). Elite Romans also actively collected Greek metalwork, jewelry, and art objects. Gone were the early days of austerity for wealthy Romans.

On the other hand ordinary Romans saw little of this splendor and wealth. In fact, the lengthy Punic Wars, which lasted more than a century, had strained the finances of most Roman people. Hannibal’s invasion left much of the farmland of southern Italy totally devastated and Italian manpower considerably reduced. Yet most people might have rebounded from these problems within a few generations, if they had not faced other serious troubles. These included political corruption, societal unrest, and repercussions of the dependence upon a huge population of disgruntled slaves.

The Impacts of Roman Clientage & Conscription

Much of Roman social life revolved around the system of clientage. Clientage consisted of networks of “patrons” – people with power and influence – and their “clients” – those who looked to the patrons for support. A patron would do things like arrange for his or her (i.e. there were women patrons, not just men) clients to receive lucrative government contracts, to be appointed as officers in a Roman legion, to be able to buy a key piece of farmland, and so on. In return, the patron would expect political support from their clients by voting as directed in the Centuriate or Plebeian Assembly, by influencing other votes, and by blocking political rivals. Likewise, clients who shared a patron were expected to help one another. These were open, publicly-known alliances rather than hidden deals made behind closed doors; groups of clients would accompany their patron into meetings of the senate or assemblies as a show of strength.

The government of the late Republic still took the form of the Plebeian Assembly, the Centuriate Assembly, the Senate, ten tribunes, two consuls, and a court system under formal rules of law. By the late Republic, however, a network of patrons and clients had emerged that largely controlled the government. Elite families of nobles, through their client networks, made all of the important decisions. Beneath this group were the equestrians: families who did not have the ancient lineages of the patricians and who normally did not serve in public office. The equestrians, however, were rich, and they benefited from the fact that senators were formally banned from engaging in commerce as of the late third century BCE. They constituted the business class of Republican Rome who supported the elites while receiving various trade and mercantile concessions.

Meanwhile, the average plebeian had long ago lost his or her representation. The Plebeian Assembly was controlled by wealthy plebeians who were the clients of nobles. In other words, they served the interests of the rich and had little interest in the plight of the class they were supposed to represent. This created an ongoing problem for Rome, one that was exploited many times by populist leaders: Rome relied on a free class of citizens to serve in the army, but those same citizens often had to struggle to make ends meet as farmers. As the rich grew richer, they bought up land and sometimes even forced poorer citizens off of their farms. Thus, there was an existential threat to Rome’s armies, and with it, to Rome itself.

A comparable pattern existed in the territories – soon provinces – conquered in war. Rome was happy to grant citizenship to local elites who supported Roman rule, and sometimes entire communities could be granted citizenship on the basis of their loyalty (or simply their perceived usefulness) to Rome. Citizenship was a useful commodity, protecting its holders from harsher legal punishments and affording them significant political rights. Most Roman subjects, however, were just that: subjects, not citizens. In the provinces they were subject to the goodwill of the Roman governor, who might well look for opportunities to extract provincial wealth for his own benefit.

Only weakening the position of farmers and plebians, was the normalizing and lengthening of conscription into the Roman army. The average term of military service for a Roman citizen between the ages of 17 and 46 was six years with a maximum of 20 years. Because experienced legionnaires were at a premium, commanders were reluctant to release them from service. But the longer a man was away in the army, the harder it was for his wife and children to keep the family farm running. Many of these families were eventually pushed off their land through outright violence or as a penalty of debt foreclosure. Sometimes the new land owner would allow the families to remain as tenants, but often they would leave in search of opportunities in the capital city of Rome. Unfortunately, things were not much better in Rome itself. By the late Republic Rome was overcrowded. Scholars estimate the number of inhabitants to have reached one million by the end of the first century BCE. Food was in such high demand that the government had to take charge of the grain supply to prevent price gouging and the resultant riots.

As family farms struggled, large-scale agricultural enterprises grew. Wealthy landowners were able to monopolize Italian farmland, importing huge numbers of slaves, and displacing the free Italian peasantry. Whereas Roman rural society had once been full of independent farmers, it was now full of slave dependent plantations, or huge landed estates. By the end of the 1st century BCE Italy’s slave population was estimated at 2 million to 3 million, about a third of the peninsula’s total. Prisoners of war and conquered civilians provided a ready supply of slaves. Most worked in agriculture or mining, and their treatment was often abominable; the fewer house slaves were usually better off. A displaced farmer would have found it very difficult to compete in the labor market against slave labor. Additionally, Roman ideology frowned on wage labor by Roman citizens. Nor was it practical for a poor famer to sue a wealthy patron who seized his land, because the plaintiff himself had to bring the accused into court. The social hierarchy, and its limits, were most visible in the Roman court of law.

At the bottom of the Roman social system were the slaves. Slaves were one of the most lucrative forms of loot available to Roman soldiers, and so many lands had been conquered by Rome that the population of the Republic was swollen with slaves. Fully one-third of the population of Italy were slaves by the first century CE. Even freed slaves, called freedmen, had limited legal rights and had formal obligations to serve their former masters as clients. Roman slaves spanned the same range of jobs noted with other slaveholding societies like the Greeks: elite slaves lived much more comfortably than did most free Romans, but most were laborers or domestic servants. All could be abused by their owners without legal consequence.

Slavery was a huge economic engine in Roman society. Much of the “loot” seized in Roman campaigns was made up of human beings, and Roman soldiers were eager to capitalize on captives they took by selling them on returning to Italy. In historical hindsight, however, slavery undermined both Roman productivity and the pace of innovation in Roman society. It simply was not necessary to seek out new and better ways of doing things in the form of technological progress or social innovations because slave labor was always available. While Roman engineering was impressive, Rome developed no new technology to speak of in its thousand-year history. Likewise, the long-term effect of the growth of slavery in Rome was to undermine the social status of free Roman citizens, with farmers in particular struggling to survive as rich Romans purchased land and built huge slave plantations.

The Conduct and Treatment of Slaves

A Roman playwright, Plautus, writing about the time of the end of the Second Punic War (201 B.C.), gives this picture of an inconsiderate master, and the kind of treatment his slaves were likely to get. Very probably conditions grew worse rather than better for the average slave household, for at least two centuries. As the Romans grew in wealth and the show of culture they did not grow in humanity.

Plautus, Pseudolus, Act. I, Sc. 2.

[Ballio, a captious slave owner, is giving orders to his servants.]

Ballio: Get out, come, out with you, you rascals; kept at a loss, and bought at a loss. Not one of you dreams minding your business, or being a bit of use to me, unless I carry on thus! [He strikes his whip around on all of them.] Never did I see men more like asses than you! Why, your ribs are hardened with the stripes. If one flogs you, he hurts himself the most: [Aside.] Regular whipping posts are they all, and all they do is to pilfer, purloin, prig, plunder, drink, eat, and abscond! Oh! they look decent enough; but they’re cheats in their conduct.

[Addressing the slaves again.] Now, unless you’re all attention, unless you get that sloth and drowsiness out of your breasts and eyes, I’ll have your sides so thoroughly marked with thongs that you’ll outvie those Campanian coverlets in color, or a regular Alexandrian tapestry, purple-broidered all over with beasts. Yesterday I gave each of you his special job, but you’re so worthless, neglectful, stubborn, that I must remind you with a good basting. So you think, I guess, you’ll get the better of this whip and of me—by your stout hides! Zounds! But your hides won’t prove harder than my good cowhide. [He flourishes it.] Look at this, please! Give heed to this! [He flogs one slave] Well ? Does it hurt ? . . . Now stand all of you here, you race born to be thrashed! Turn your ears this way! Give heed to what I say. You, fellow! that’s got the pitcher, fetch the water. Take care the kettle’s full instanter. You who’s got the ax, look after chopping the wood.

Slave: But this ax’s edge is blunted.

Ballio: Well; be it so! And so are you blunted with stripes, but is that any reason why you shouldn’t work for me? I order that you clean up the house. You know your business; hurry indoors. [Exit first slave]. Now you [to another slave] smooth the couches. Clean the plate and put in proper order. Take care that when I’m back from the Forum I find things done—all swept, sprinkled, scoured, smoothed, cleaned and set in order. Today’s my birthday. You should all set to and celebrate it. Take care—do you hear—to lay the salted bacon, the brawn, the collared neck, and the udder in water. I want to entertain some fine gentlemen in real style, to give the idea that I’m rich. Get indoors, and get these things ready, so there’s no delay when the cook comes. I’m going to market to buy what fish is to be had. Boy, you go ahead [to a special valet], I’ve got to take care that no one cuts off my purse.

How to Manage Farm Slaves

Cato the Elder passed as the incarnation of all worldly wisdom among Romans of the second century B.C. The precepts here given were undoubtedly put into effect on his own farms. During the early Republic, when the estates were small, there seems to have been a fair amount of kindly treatment awarded the slaves; as the farms grew larger the whole policy of the masters, by becoming more impersonal, became more brutal. Cato does not advocate deliberate cruelty—he would simply treat the slaves according to cold regulations, like so many expensive cattle.

Cato the Elder, Agriculture, chs. 56-59

Country slaves ought to receive in the winter, when they are at work, four modii [Davis: One modius equals about a quarter bushel] of grain; and four modii and a half during the summer. The superintendent, the housekeeper, the watchman, and the shepherd get three modii; slaves in chains four pounds of bread in winter and five pounds from the time when the work of training the vines ought to begin until the figs have ripened.

Wine for the slaves. After the vintage let them drink from the sour wine for three months. The fourth month let them have a hemina [Davis: about half a pint] per day or two congii and a half [Davis: over seven quarts] per month. During the fifth, sixth, seventh, and eighth months let them have a sextarius [Davis: about a pint] per day or five congii per month. Finally, in the ninth, tenth, and the eleventh months, let them have three hemina [Davis: three-fourths of a quart] per day, or an amphora [Davis: about six gallons] per month. On the Saturnalia and on Compitalia each man should have a congius [Davis: something under three quarts].

To feed the slaves. Let the olives that drop of themselves be kept so far as possible. Keep too those harvested olives that do not yield much oil, and husband them, for they last a long time. When the olives have been consumed, give out the brine and vinegar. You should distribute to everyone a sextarius of oil per month. A modius of salt apiece is enough for a year.

As for clothes, give out a tunic of three feet and a half, and a cloak once in two years. When you give a tunic or cloak take back the old ones, to make cassocks out of. Once in two years, good shoes should be given.

Winter wine for the slaves. Put in a wooden cask ten parts of must (non-fermented wine) and two parts of very pungent vinegar, and add two parts of boiled wine and fifty of sweet water. With a paddle mix all these thrice per day for five days in succession. Add one forty-eighth of seawater drawn some time earlier. Place the lid on the cask and let it ferment for ten days. This wine will last until the solstice. If any remains after that time, it will make very sharp excellent vinegar.

Source: https://blogs.memphis.edu/pbrand/slavery-texts/

Slave Revolts

While the increased reliance on slavery negatively impacted many plebians and destabilized the republic, those who suffered most under the system were of course the slaves. This suffering led to numerous slave revolts, which further worked to undermine the central authority of the ruling Roman families. The first slave revolt, also known as the First Servile War, erupted in Sicily in 135 BCE and it took 4 years for the Romans to crush. The second revolt, also in Sicily, began in 104 BCE and again took 4 years for the Roman legions to overcome. Then the third revolt exploded in 73 BCE in mainland Italy, and proved to be the most serious of them all. Perhaps the severity of this insurrection was due to the fact that it was led by a Gladiator.

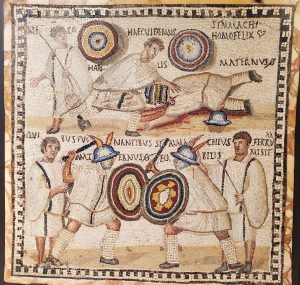

Gladiators were a subset of slaves, though a few were volunteers, who entertained the Roman masses by fighting (at times to the death) against other gladiators, condemned criminals, and even wild animals. The first record of gladiators can be found in funerary rites during the First Punic War. By the Second Punic War, gladiatorial games served to both celebrate military victories and inspire further military expansion by rehashing previous defeats. Criminals were punished by being forced to play, often impossible, gladiatorial games also served to display and spread Rome’s message of power and invulnerability. These shows were meant to instill fear and respect in the larger populous. And finally, gladiatorial games were in fact meant to entertain the masses. Many Gladiators even became Roman celebrities’. Gladiators were part warrior and part athlete whether or not they were free or enslaved.

By the end of the second century BCE, the gladiatorial games began to take on political significance as well. Gladiatorial games offered their sponsors, usually aspiring or current magistrates, extravagantly expensive but effective opportunities for self-promotion to their clients and potential voters. Here it is important to note that all gladiatorial games were free for all to attend, though the better seats were reserved for purchase, so they became effective campaign rallies. As gladiators became more famous, and lucrative to political leaders, the games transformed into a big business for trainers, owners, and politicians who could command the gladiators’ services. Gladiators who survived successive battles became celebrities, and were sought after by powerful men and women in the Roman Republic. Often famous gladiators could make large sums of money by selling their sexual services to high class Roman women seeking a thrill. Graffiti unearthed in Pompeii proves the famous stature of gladiators. One such inscription was dedicated to a star of the gladiatorial arena whom “all the girls sigh for.”

Depending on the theme of the game, remember they were for entertainment, opponents were armed with various specialized weapons or none at all. Volunteer gladiators, or those who had won several battles, became known for certain styles of fighting with specific weaponry. For example, Murmillo were heavily armored gladiators that used a large, oblong shield and a sword called a gladius while Retiarius, were gladiators who wielded a large net and a trident, attempting to trap their opponents under their net prior to stabbing them with their three-pronged spear. As one might imagine, these were skilled fighters, and thus did receive specialized training in gladiatorial schools, who for the most part had not been condemned to serve as gladiators as punishment.

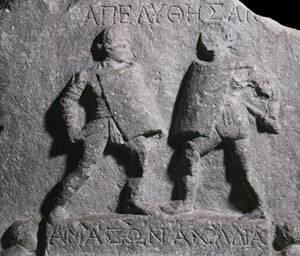

While female Christians are well documented as being forced into the gladiatorial arenas as punishment, few historical works have highlighted female gladiators. Surprisingly, there were hundreds of female gladiators who volunteered and trained to participate in the games. These women came from all levels of society, from enslaved women to middle class to elite senatorial wives. Their motives for fighting ranged from seeking freedom from enslavement to the thrill of the combat. The fact that the Roman Senate passed laws prohibiting the participation of elite women in gladiatorial games in 11 and 19 CE underscores how common the practice may have been.

According to Roman historian Cassius Dio, Nero held an exhibition in 59 CE “that was at once most disgraceful and most shocking, when men and women not only of the [middle class] but even of the senatorial order…drove horses, killed wild beasts and fought as gladiators, some willingly and some sore against their will.” So clearly, the laws were ineffective in preventing elite women from participating in gladiatorial games.

During the games, the audience was seated in order of social rank, ranging from slaves to senators to the emperor himself. The floor of the arena, which in Latin means sand, was called such because the floor needed to be made of sand to be able to soak up the blood of the gladiators and/or animals who died in the ring. At times up to 100 gladiators died in a single occasion. While all gladiators understood that fights could end in death, often matches between trained gladiators ended with neither opponent dying. This was mainly due to pragmatic reasons, it was expensive to find and train new gladiators. Thus, most matches pitting exotic animals (from hippos to lions and tigers) against gladiators were reserved for criminals or prisoners condemned to death via the gladiatorial ring.

And gladiatorial games spread well beyond Rome, throughout the lands conquered by the Republic. Conquered cities took part in these games or combat before large crowds. We can best see this in the proliferation of coliseums that to this day dot the European landscape. Without a doubt the gladiatorial games were a quintessential part of Roman culture that they transported across Western Europe.

Spartacus Revolt

According to differing sources and their interpretation, Spartacus either was an auxiliary Thracian soldier from the Roman legions later condemned to slavery, or a captive taken by the legions. Either way, after his designation as an enslaved gladiator, Spartacus was trained at the gladiatorial school of Capua. Then, in 73 BCE, Spartacus was among a group of gladiators who rebelled against the Roman hierarchy, plotting an escape from the school. While the plan for revolt was discovered before the gladiators could execute it, Spartacus and his accomplices were not deterred. Approximately 70 gladiators in training raided the kitchen, taking all the implements they could find to use as weapons and fought their way out of the school. During the fight, they were able to seize several wagons of gladiatorial weaponry and armor.

A first, the gladiators remained in the outskirts of Capua, raiding the countryside and recruiting other slaves to join their revolt. After several weeks, they sought a more defensible position and climbed to the top of Mount Vesuvius. At this point most sources claim that the group chose two leaders, one of them being Spartacus, to organize the group. This included training the non-gladiatorial slaves in combat. And lucky for the escaped gladiators, they had time to prepare to face the Roman legions as they were busy elsewhere in the now sprawling Republic.

At this point most of the Roman legions were engaged in fighting a revolt in the province of Hispania. Additionally, the seriousness of the gladiatorial revolt was not immediately understood and at first, the Romans viewed the conflict as more of a policing matter. Thus, they first dispatched their militia to besiege Spartacus and his camp hoping that without access to food and other supplies the gladiators would surrender quickly. But, this was not the case. Instead, the militia faced a surprise attack when Spartacus’s group, who had made ropes from vines, climbed down the cliff side of Mt. Vesuvius and attacked the unfortified Roman camp in the rear, killing most of them. The rebels soon after defeated a second expedition, nearly capturing the commander, killing his lieutenants and seizing their military equipment. These victories only inspired more slaves to flee their masters, eagerly joining with the seemingly invincible Spartacan forces. Even some free, though poor Romans joined their ranks (such as herdsmen). At the group’s height reports counted up to 70,000 men.

In the spring of 72 BCE, the slaves left their Mt. Vesuvius encampments and began to march northward, possibly to escape Roman authority. At the same time, the Roman Senate, alarmed by the defeat of the Roman military forces, dispatched a pair of consular legions. The two legions were initially successful—defeating a group of 30,000 rebels but then were defeated by Spartacus. The defeat of the legions struck fear into the Senate, and so they charged Marcus Licinius Crassus, the wealthiest man in Rome, with ending the rebellion. Crassus was to command eight legions, approximately 40,000 trained Roman soldiers (who were to join with the already positioned military factions), against Spartacus and his group. In early 71 BCE. Crassus’ legions were victorious in several engagements, forcing Spartacus not only to stop moving northward, but to return south. By the end of 71 BCE, Spartacus was encamped in Rhegium (Reggio Calabria), near the Strait of Messina, in many ways trapped.

But Spartacus still had a plan. He made an agreement with a group of Sicilian pirates to ferry he and about 2,000 of his allies to Sicily where he hoped to incite a slave revolt and gather reinforcements. From there he planned an invasion of Rome. However, he was betrayed by the pirates, who took payment and then abandoned the rebels, leaving them stranded with Crassus’s legions fast approaching. Spartacus’ forces were once again under siege and cut off from their supplies.

Just as Spartacus found himself in an untenable position versus Crassus, Pompey’s legions returned from Hispania and were immediately ordered by the Senate to head south to aid Crassus. In the end, Spartacus’s troops were no match for the professionally trained and well supplied Roman legions. In a last stand, the rebels were routed completely, with most killed on the battlefield. Some reports say that Spartacus died on the battlefield, while others claim he was crucified along with hundreds of his followers. As a message to anyone considering defying the Roman Senate, they executed hundreds of rebels via crucifixion and then lined the Appian Way (the road from Capua to Rome) with their bodies. As his body was never recovered, mystery remains behind Spartacus’s end, leading to one of the most famous movie scenes from the 1960 film Spartacus.

The End of the Republic

The Roman Republic lasted for roughly five centuries. It was under the Republic that Rome evolved from a single town to the heart of an enormous empire. Despite the evident success of the republican system, however, there were inexorable problems that plagued the Republic throughout its history, most evidently the problem of wealth and power. Roman citizens were, by law, supposed to have a stake in the Republic. They took pride in who they were and it was the common patriotic desire to fight and expand the Republic among the citizen-soldiers of the Republic that created, at least in part, such an effective army. At the same time, the vast amount of wealth captured in the military campaigns was frequently siphoned off by elites, who found ways to seize large portions of land and loot with each campaign. By around 100 BCE even the existence of the Plebeian Assembly did almost nothing to mitigate the effect of the debt and poverty that afflicted so many Romans thanks to the power of the clientage networks overseen by powerful noble patrons.

The key factor behind the political stability of the Republic up until the aftermath of the Punic Wars was that there had never been open fighting between elite Romans in the name of political power. In a sense, Roman expansion (and especially the brutal wars against Carthage) had united the Romans; despite their constant political battles within the assemblies and the senate, it had never come to actual bloodshed. Likewise, a very strong component of Roman ethics was the idea that political arguments were to be settled with debate and votes, not clubs and knives. Both that unity and that emphasis on peaceful conflict resolution within the Roman state itself began to crumble after the sack of Carthage.

The Gracchi

Beyond the unrest caused by the slave revolts, many Romans were worried about the military dimension of the agrarian crisis. In modern societies, draftees are often the poorest people. In Rome, military service was a prestigious activity, one conducted by wealthy property owning citizens (with slaves used as needed). As fewer and fewer citizens/potential soldiers could afford to own and maintain property, however, during the second century it became necessary to reduce the property qualification several times. By 150 BCE a conscript had to own property worth only 400 denari, basically a very small house, owning large plots of land was no longer necessary. If the peasantry continued to decline, Rome would either have to drop the property qualifications all together for the military or stop fielding armies. Something had to be done…resulting in contentious Senatorial debate and eventually revolution.

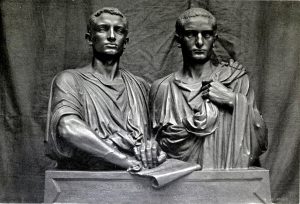

The first step toward violent revolution in the Republic was the work of the Gracchus brothers – remembered historically as the Gracchi (i.e. “Gracchi” is the plural of “Gracchus”). The older of the two was Tiberius Gracchus, a rich but reform-minded politician. Tiberius was the son of a distinguished general and ambassador and one of the ten tribunes for the year 133 BCE. He seemed to be an excellent spokesperson for a group of prominent senators who backed land reform. Tiberius, among others, was worried that the free, farm-owning common Roman would go extinct if the current trend of rich landowners seizing farms and replacing farmers with slaves continued. Without those commoners, Rome’s armies would be drastically weakened. Thus, he managed to pass a bill through the Centuriate Assembly that would limit the amount of land a single man could own, distributing the excess to the poor. Tiberius’s law restored the roughly 320 acre limit to the amount of public land a person could own. A commission was then set up to repossess excess land and redistribute it to the poor, in small lots that were to be inalienable-that is, the wealthy could not buy them back. The former landowners would be reimbursed for the improvements they had made, such as buildings or plantings.

Even though Tiberius Gracchus’s bill was fairly moderate, the Senate was horrified and fought bitterly to reverse the bill. To keep his reforms in place Tiberius broke with tradition twice, first deposing one of his fellow tribunes (and opponents) Octavius and then running for a second term. Shocked and angered conservative senators then conspired to club Tiberius Gracchus to death in 133 BCE. This massacre marked the first time in the Republic that a political debate was settled by bloodshed in Rome itself. All ancient sources agree this was the beginning of a century of revolution. Tiberius’s killers had not merely committed murder, but had attacked the traditional inviolability of the tribunes. Yet over the next century public violence grew to be a commonly used weapon of politics in the Republic. Meanwhile, the land commission went ahead with its work, even without Tiberius.

A few years following his assassination, Tiberius’s brother Gaius Gracchus took up the cause, also becoming tribune. He attacked corruption in the provinces, allying himself with the equestrian class by allowing equestrians to serve on juries that tried corruption cases. He also tried to speed up land redistribution. His most radical move was to try to extend full citizenship to all of Rome’s Italian subjects, which would have effectively transformed the Roman Republic into the Italian Republic. Here, he lost even the support of his former allies in Rome, and he killed himself in 121 BCE rather than be murdered by another gang of assassins sent by senators. Unfortunately, despite his death, another 3,250 of Gaius’s supporters were assassinated in short order.

The reforms of the Gracchi were temporarily successful: even though they were both killed, the Gracchi’s central effort to redistribute land accomplished its goal. The land commission created by Tiberius remained intact until 118 BCE, by which time it had redistributed huge tracts of land held illegally by the rich. Despite their vociferous opposition, the rich did not suffer much, since the lands in question were “public lands” largely left vacant in the aftermath of the Second Punic War, and normal farmers did enjoy benefits. Likewise, despite Gaius’s death, the Republic eventually granted citizenship to all Italians in 84 BCE, after being forced to put down a revolt in Italy. In hindsight, the historical importance of the Gracchi was less in their reforms and more in the manner of their deaths – for the first time, major Roman politicians had simply been murdered (or killed themselves rather than be murdered) for their politics. It became increasingly obvious that true power was shifting away from rhetoric and toward military might.

There was also a growing, clear social/economic divide within the Roman Republic. The violence surrounding the Gracchi brothers had divided the political community into two loose groupings. On one side were the optimates “the best people” or conservatives who asserted the rule of the Senate against the popular tribunes and the maintenance of the estates of the wealthy in spite of the agrarian crisis. On the other side were the populares “men of the people” who challenged the rule of the Senate in the name of relief of the poor. The populares were not democrats. Like the optimates, they were Roman nobles who believed in hierarchy, but they advocated the redistribution of wealth and power as a way of restoring stability and strengthening the military.

A contemporary of the Gracchi, a populares general named Gaius Marius, took further steps that eroded the traditional Republican system in response to a near full-scale military crisis. By 100 BCE Rome’s agrarian crisis was a full-scale military crisis. Roman armies under senatorial commanders fared poorly; both in present day Algeria and in southern Gaul against Germanic invaders. Marius recognized the political and social origins of Rome’s declining military might and set out remedy the problem, combining political savvy with effective military leadership. Marius was both a consul (elected an unprecedented seven times despite being the first in his family to even enter politics) and a general, and he used his power to first eliminate the property requirement entirely for membership in the army. This allowed the poor to join the army in return for nothing more than an oath of loyalty, one they swore to their general rather than to the Republic. The army would then provide the recruits with weaponry and training, something that soldiers had had to fund themselves in the past, hence the property requirement. As a result, Roman soldiers were no longer peasants doing part-time military service but rather were landless men making a profession of the military. In addition to the training and equipment, they would also receive a stable pay and a portion of any booty taken in battle. But, they were also forbidden to marry. Regardless, the military became totally devoted to Marius.

Marius made several other changes to streamline and strengthen the Roman army. Camp followers were reduced in number (in the past families had followed their fathers or husbands and this was now forbidden) and individual solders were made to carry their own equipment. To meet the Germans, who attacked in overwhelming waves, maniples were reorganized and combined into larger units called cohorts, rendering the army firmer and more cohesive when need be. And his policies worked, as the revitalized Roman legions won victory after victory against enemies in both Africa and Germany. Following successful battles, Marius then distributed land and farms to his poor soldiers. This made him a people’s hero, but it also terrified the nobility in Rome because he was able to bypass the usual Roman political machine. His decision to eliminate the property requirement meant that his troops were totally dependent on him for loot and land distribution after campaigns, undermining their allegiance to the Republic.

The Senate recognized the threat that Marius’s loyal army posed to their power, and thus they declared all of Marius’s land distributions invalid, taking the land away from the soldiers who had just received plots in Germany and northern Africa. Angry, and confident in their military prowess, soldiers in Rome began to riot, demanding their land and for Marius to replace the Senate. While Marius had pushed the bounds of his power militarily, he did not want to go against the very framework of the Republic, and in the face of violence he resigned as tribune.

“Social War”

The Republic at this point was very weak, but it would become still weaker as the result of two wars. First Rome’s Italian allies rose up against them in a bloody and bitter civil war known as the “Social War” from 91 to 89 BCE. The conflict gets this name because it was a war between socii or allies. The Italian allies fought hard, and Rome, in order to prevail, had to concede to them what they had demanded long ago (and what the Gracchi tried to give them); Full Roman Citizenship. The war wrought devastation in the countryside, further destabilizing the Republic and only hurting independent farmers more. The other conflict of the period pitted Rome against a rebellious king in northern Anatolia who conquered a bit of Roman territory and proceeded to slaughter numerous Italian businessmen and tax collectors there. Once again a military man rose to save the day for Rome, this time Marius’s rival and former lieutenant, Optimate Lucius Cornelius Sulla. He became consul in the year 88 BCE.

General Sulla followed in Marius’s footsteps by recruiting soldiers directly and using his military power to bypass the government, angering the Senate. Then in the aftermath of another Italian revolt, prompted by Rome’s delay in bequeathing citizenship to its Italian allies, the Assembly took Sulla’s command of Roman legions away and gave it to Marius in return for his support in enfranchising the people of the Italian cities. Sulla promptly marched on Rome with his army, forcing Marius to flee. A civil war in the very streets of Rome was barely avoided, but not for long.

Marius, though deposed and out of graces with the Senate, was still very influential in military circles. And he both disagreed with Sulla’s policies and was jealous of his power, so when Sulla was engaged with another conflict in the east (against the anti-Roman king Mithridates), Marius gathered a group of soldiers and marched on Rome, retaking the city and settling scores. Marius himself soon died (of old age), but his followers remained united in an anti-Sulla coalition under a friend and colleague of Marius named Cinna.

After defeating Mithridates, Sulla returned and a full-scale civil war shook Rome in 83 – 82 BCE. It was horrendously bloody, with some 300,000 men joining the fighting and many thousands killed. After Sulla’s ultimate victory he had thousands of Marius’s supporters imprisoned. From these men he also confiscated their land, disenfranchised their sons, and had them executed. Sulla then divided the confiscated land up among his loyal troops, about 80,000 men. If anyone tried to oppose the ruling, he expelled them as well. He then assumed the title of dictator, something only supposed to be used for 6 months during a state of emergency, but he did so without the vote of the Senate nor with any explicit term limit. As dictator, Sulla greatly strengthened the power of the Senate (expanding its members from 300 to 600) at the expense of the Plebeian Assembly, abolished trials before popular assemblies and equestrian-staffed courts (created by Gaius Gracchus) replacing them with seven courts whose juries would all be Senators, and had his enemies murdered and their property seized. After two years, in 79 BCE, Sulla felt he had accomplished his goal to stabilize Rome and remove all power from the populares. He then retired to a life of debauchery in his private estate, where he soon died from a mysterious illness.

The problem for the Republic was that, even though Sulla ultimately proved that he was loyal to republican institutions, in that he only kept the mantle of Dictator for two years, other generals might not be in the future. Sulla could have simply held onto power indefinitely thanks to the personal loyalty of his troops. Additionally, discontent still smoldered, perhaps even more so, amongst the poor and especially now amongst the men who Sulla had confiscated land from. Others now sought to do what Sulla had done, pursuing personal power over the Senate and seeking to use the weak points of the Republic against itself.

Julius Caesar & the Triumvirate

Thus, the Roman Republic was in a precarious state when a new politician and general named Julius Caesar emerged and quickly became increasingly powerful. He ultimately began to replace the Republic with an empire, following in the footsteps of Marius and Sulla. Julius Caesar’s rise to power is a complex story that reveals just how murky Roman politics were by the time he became an important political player in about 70 BCE. Caesar himself was both a brilliant general and a shrewd politician; he was skilled at keeping up the appearance of loyalty to Rome’s ancient institutions while exploiting opportunities to advance and enrich himself and his family. He was loyal, in fact, to almost no one, even old friends who had supported him, and he also cynically used the support of the poor for his own gain.

Two powerful politicians, Pompey and Crassus (both of whom had risen to prominence as supporters of Sulla with Pompey even divorcing his first wife to marry Sulla’s stepdaughter Aemilia), joined together to crush the slave revolt of Spartacus in 70 BCE and were elected consuls because of their success. Pompey was one of the greatest Roman generals, and he soon left to eliminate piracy from the Mediterranean, to conquer the Jewish kingdom of Judea, and to crush an ongoing revolt in Anatolia. He returned in 67 BCE and asked the Senate to approve land grants to his loyal soldiers for their service, a request that the Senate refused because it feared his power and influence with so many soldiers who were loyal to him instead of the Republic. Pompey reacted by forming an alliance with Crassus and Julius Caesar, who was a member of an ancient patrician family. This group of three is known in history as the First Triumvirate.

Each member of the Triumvirate wanted something specific: Caesar (a populares) hungered for glory and wealth and hoped to be appointed to lead Roman armies against the Celts in Western Europe, Crassus wanted to lead armies against Parthia (i.e. the “new” Persian Empire that had long since overthrown Seleucid rule in Persia itself), and Pompey (an optimate) wanted the Senate to authorize land and wealth for his troops. The three of them had so many clients and wielded so much political power that they were able to ratify all of Pompey’s demands, and both Caesar and Crassus received the military commissions they hoped for. Caesar was appointed general of the territory of Gaul (present-day France and Belgium) and he set off to fight an infamous Celtic king named Vercingetorix.

From 58 to 50 BCE, Caesar waged a brutal war against the Celts of Gaul. He was both a merciless combatant, who slaughtered whole villages and enslaved hundreds of thousands of Celts (killing or enslaving over a million people in the end), and a gifted writer who wrote his own accounts of his wars in excellent Latin prose. His forces even invaded England, establishing a Roman territory there that lasted centuries. All of the lands he invaded were so thoroughly conquered that the descendants of the Celts ended up speaking languages based on Latin, like French, rather than their native Celtic dialects.

Caesar’s victories made him famous and immensely powerful, and they ensured the loyalty of his battle-hardened troops. In Rome, senators feared his power and called on Caesar’s former ally Pompey to bring him to heel (Crassus had already died in his ill-considered campaign against the Parthians; his head was used as a prop in a Greek play staged by the Parthian king). Pompey, fearing his former ally’s power and perhaps recalling their political differences (populares vs. optimate), agreed and brought his armies to Rome. The Senate then recalled Caesar after refusing to renew his governorship of Gaul and his military command, or allowing him to run for consul in absentia.

The Senate hoped to use the fact that Caesar had violated the letter of republican law while on campaign to strip him of his authority. Caesar had committed illegal acts, including waging war without authorization from the Senate, but he was protected from prosecution so long as he held an authorized military command. By refusing to renew his command or allow him to run for office as consul, he would be open to charges. His enemies in the Senate feared his tremendous influence with the people of Rome, so the conflict was as much about factional infighting among the senators as fear of Caesar imposing some kind of tyranny.

Caesar knew what awaited him in Rome – charges of sedition against the Republic – so he simply took his army with him and marched to Rome. In 49 BCE, he dared to cross the Rubicon River in northern Italy, the legal boundary over which no Roman general was allowed to bring his troops; he reputedly announced that “the die is cast” and that he and his men were now committed to either seizing power or facing total defeat. The brilliance of Caesar’s move was that he could pose as the champion of his loyal troops as well as that of the common people of Rome, whom he promised to aid against the corrupt and arrogant senators; he never claimed to be acting for himself, but instead to protect his and his men’s legal rights and to resist the corruption of the Senate.

Pompey had been the most powerful man in Rome, both a brilliant general and a gifted politician, but he did not anticipate Caesar’s boldness. Caesar surprised him by marching straight for Rome. Pompey only had two legions, both of whom had served under Caesar in the past, and he was thus forced to recruit new troops. As Caesar approached, Pompey fled to Greece, but Caesar followed him and defeated his forces in battle in 48 BCE. Pompey himself escaped to Egypt, where he was promptly murdered by agents of the Ptolemaic court who had read the proverbial writing on the wall and knew that Caesar was the new power to contend with in Rome. Subsequently, Caesar came to Egypt and stayed long enough to forge a political alliance, and carry on an affair, with the queen of Egypt: Cleopatra VII, last of the Ptolemaic dynasty. Caesar helped Cleopatra defeat her brother (to whom she was married, in the Egyptian tradition) in a civil war and to seize complete control over the Egyptian state. She also bore him his only son, Caesarion.

Caesar returned to Rome two years later, after hunting down Pompey’s remaining loyalists. There, he had himself declared dictator for life (purportedly after considering taking the title of King with the support of Cleopatra) and set about creating a new version of the Roman government that answered directly to him. He filled the Senate with his supporters and established military colonies in the lands he had conquered as rewards for his loyal troops (which doubled as guarantors of Roman power in those lands, since veterans and their families would now live there permanently). He established a new calendar, which included the month of “July” named after him, and he regularized Roman currency. Then he promptly set about making plans to launch a massive invasion of Persia.

And at home he sponsored a huge number of reforms. His political goal was to elevate Italians and others at the expense of old Roman families. To achieve this, Caesar conferred Roman citizenship liberally, on all of Gaul as well as on certain provincial towns. He again enlarged the Senate from 600 to 900, adding his supporters, including some Gauls, to the membership. Caesar sponsored social and economic reforms to help the lower classes, reducing debt and settling veterans and poor citizens in colonies outside of Italy. He undertook a grand public building program in the city of Rome. He also adopted the Egyptian calendar of 365 and ¼ days on January 1, 45 BCE. He called this the Julian calendar, named after none other than himself.

While many Romans were dedicated to Caesar, others feared his motivations and viewed many of his actions as attacks on the very fabric of the Republic. In the end, mistrust of Caesar exploded on March 15, 44 BCE (the Ides of March in the Julian calendar) when 60 senators stabbed Caesar to death. The assassination took place in the portico attached to the Theater of Pompey, in front of a statue of Pompey himself, where the Senate was meeting that day. The assassins called themselves “The Liberators,” believing that they were freeing themselves from tyranny just as the founders of the Republic had done centuries earlier. Indeed, one of the chief conspirators, Marcus Junius Brutus claimed descent from Lucius Tarquins who was believed to have established the Republic (think back to “The Rape of Lucretia”). Brutus had been a magistrate, military officer, and provincial administrator, as well as confidant of Caesar. The assassination of Caesar threw Rome back into turmoil. Civil war followed for the next 13 years, first between the Liberators and Caesar’s supporters and then between the two leading Caesarians (followers of Caesar). The final struggle pitted Mark Anthony, Caesar’s chief lieutenant and Cleopatra’s new lover, against Octavian, Caesar’s grandnephew, adopted son, and heir to both Caesar’s name and fortune.

Mark Antony vs. Octavian

Following his death, Caesar’s right-hand man, a skilled general named Mark Antony, joined with Octavian and another general named Lepidus to form the “Second Triumvirate.” In 43 BCE they seized control in Rome and then launched a successful campaign against the old republican loyalists, killing off the men who had killed Caesar and murdering the strongest senators and equestrians who had tried to restore the old institutions. Mark Antony and Octavian soon pushed Lepidus to the side and divided up control of Roman territory – Octavian taking Europe and Mark Antony taking the eastern territories and Egypt. This was an arrangement that was not destined to last; the two men had only been allies for the sake of convenience, and both began scheming as to how they could seize total control of Rome’s vast empire.

Mark Antony moved to the Egyptian city of Alexandria, where he set up his court. He followed in Caesar’s footsteps by forging both a political alliance and a romantic relationship with Cleopatra, and the two of them were able to rule the eastern provinces of the Republic in defiance of Octavian. They then declared, via the Donations of Alexandria in 34 BCE, that the eastern portion of the Republic would be divided between Antony and Cleopatra’s children, ensuring Octavian could never unite the empire. Alexander Helios was named king of Armenia, Media and Parthia (territories which were not for the most part under the control of Rome), his twin Selene got Cyrenaica and Libya, and the young Ptolemy Philadelphus was awarded Syria and Cilicia. As for Cleopatra, she was proclaimed Queen of Kings and Queen of Egypt, to rule with Caesarion (Ptolemy XV Caesar, son of Cleopatra by Julius Caesar), King of Kings and King of Egypt. Most important of all, Caesarion was declared THE legitimate son and heir of Caesar. These proclamations caused a fatal breach in Antony’s relations with Rome.

While the distribution of nations among Cleopatra’s children was hardly a conciliatory gesture, it did not pose an immediate threat to Octavian’s political position. Far more dangerous was the acknowledgment of Caesarion as legitimate son and heir to Caesar. Octavian’s base of power was his link with Caesar through adoption, which granted him much-needed popularity and loyalty of the legions. To see this situation attacked by a child borne by the richest woman in the world was something Octavian could not accept. Another civil war was beginning.

During 33 and 32 BCE, a propaganda war was fought in the political arena of Rome, with accusations flying between sides. Antony (still in Egypt) divorced his Roman wife Octavia (Octavian’s sister) and accused Octavian of being a social upstart, of usurping power, and of forging his adoption papers by Caesar. Meanwhile, Octavian claimed that Antony was under Cleopatra’s thumb (which is unlikely: the two of them were both savvy politicians and seem to have shared a genuine affection for one another) and was breaking with traditional Roman values, eventually seizing on this behavior to claim that he was the true protector of Roman morality. Octavian even produced a will that Mark Antony had supposedly written ceding control of Rome to Cleopatra and their children on his death; whether or not the will was authentic, it fit in perfectly with the publicity campaign on Octavian’s part to build support against his former ally in Rome.

By the end of 32 BCE, Octavian charged Antony with treason (of illegally keeping provinces that should be given to other men by lots, as was Rome’s tradition, and of starting wars against foreign nations without the consent of the Senate) and the Senate removed Antony’s magistrate powers. The Senate then declared ware against Cleopatra, as Octavian had no wish to advertise his role in perpetuating Rome’s internecine bloodshed. Octavian claimed he was only interested in defeating Cleopatra, which led to broader Roman support because it was not immediately stated that it was yet another Roman civil war. Antony and Cleopatra’s forces were already fairly scattered and weak due to a disastrous campaign against the Persians a few years earlier. In 31 BCE, at the Battle of Actium (in northwestern Greece) Octavian defeated Mark Antony’s forces, which were poorly equipped, sick, and hungry, and destroyed the Egyptian navy. Antony and Cleopatra’s soldiers were starved out by a successful blockade engineered by Octavian and his friend and chief commander Agrippa, and the unhappy couple killed themselves the next year in exile. Octavian was 33. As his grand-uncle had before him, Octavian began the process of manipulating the institutions of the Republic to transform it into something else entirely: an empire.

A Truly Shakespearean Love Story

While Marc Antony and Cleopatra had their highs and lows over their ten year relationship, they truly seemed to have had genuine love for one another. This is best proved in their deaths. Despite Cleopatra’s fortune and Antony’s military prowess, in the end they were no match for Octavian. Nor did Cleopatra’s actions help the situation. While Octavian’s troops marched closer to Alexandria, Cleopatra was occupied building a new “temple to Isis,” which she called her mausoleum. Following the announcement of the Donation of Alexandria, Cleopatra was often seen dressed as the goddess Isis, with Antony dressed as Dionysus.

As she arranged her mausoleum/temple, Cleopatra stuffed it with gems, jewelry, works of art, gold, royal robes, and stores of cinnamon and frankincense. She planned to use the treasure as either punishment or in negotiations. Cleopatra was secretly negotiating with Octavian, unbeknownst to Antony. Cleopatra hoped to at the very least save her children, and if that was not possible to burn her treasure and force Octavian to watch. Her plan was set in motion when she sent word to Antony that she had killed herself, knowing that he would soon follow. She was right. According to Plutarch, when Antony was told of Cleopatra’s death, he said:

O Cleopatra, I am not distressed to have lost you, for I shall straightaway join you; but I am grieved that a commander as great as I should be found to be inferior to a woman in courage.

But, Antony did not perish quickly, and when Cleopatra heard that he was on his deathbed, she sent for him. He died in her arms in her mausoleum. After Antony breathed his last, Cleopatra fought on, attempting to negotiate with Octavian. But when all hope was lost and she was captured by Octavian’s forces, Cleopatra snuck poison (or in some versions an asp snake) past Octavian’s guards. She died while imprisoned by Octavian, avoiding the punishment she knew he would force her to endure and still hoping her children would be spared. Octavian did in fact spare Cleopatra and Antony’s children, giving them to his sister Octavia to raise. However, Caesarion (son of Caesar and Cleopatra) was murdered. Honoring Cleopatra’s last request, Octavian had Cleopatra and Antony buried side by side.

Octavian to Augustus/Republic to Empire

The height of Roman power coincided with the first two hundred years of the Roman Empire, a period that was remembered as the Pax Romana: the Roman Peace. It was possible during the period of the Roman Empire’s height, from about 1 CE to 200 CE, to travel from the Atlantic coast of Spain or Morocco all the way to Mesopotamia using good roads, speaking a common language, and enjoying official protection from banditry. The Roman Empire was as rich, powerful, and glorious as any in history up to that point, but it also represented oppression and imperialism to slaves, poor commoners, and conquered peoples.

Octavian was unquestionably the architect of the Roman Empire. Despite the violent beginnings of his rule, Octavian proved to be an astute politician and a sharp judge of others. He learned and heeded the lessons of Caesar’s greatest mistakes. He understood that the Roman elite, however weakened, was still strong enough to oppose a ruler who flaunted monarchical power. To avoid a second Ides of March, therefore, Octavian was infinitely diplomatic. Since the term Rex (king) would have been odious to his fellow Romans, Augustus instead referred to himself as Princeps Civitatus, meaning “first citizen.” He used the Senate to maintain a facade of republican rule, instructing senators on the actions they were to take; a good example is that the Senate “asked” him to remain consul for life, which he graciously accepted. Octavian wanted advice without dissent. He used the senate, or rather a committee of senators and magistrates, as a sounding board; the group evolved into a permanent advisory body. Ordinary senate meetings, however, what with carefully planted informers, lost their freedom of speech. The popular assemblies fared even worse, as their powers were limited and eventually transferred to the senate.

In 27 BCE the Senate awarded Octavian the honorific Augustus: “illustrious” or “semi-divine.” It is by that name, Augustus Caesar, that he is best remembered. Then in 23 BCE, Octavian assumed the position of tribune for life, the office that allowed unlimited power in making or vetoing legislation. All soldiers swore personal oaths of loyalty to him, and having conquered Egypt from his former ally Mark Antony, Octavian was worshiped as Egypt’s latest pharaoh. Augustus was the most powerful Roman ruler recorded.

Augustus divided the provinces between himself and the senate. To check any new would-be Caesar or other tyrant, Augustus kept the frontier provinces, where the main concentration of armies resided, as well as grain-rich Egypt within his grasp. The local commanders were all loyal equestrians who owed their success directly to Augustus. Most of the other provinces continued to be ruled as before by senators serving as governors. Nor would unruly crowds within Rome or other larger cities be tolerated. Augustus established Rome’s first police force to control the urban environs in addition to his own personal guards. Called the praetorians (the name used for a Roman general’s personal bodyguard) or Praetorian Guard, the force would play a crucial role in future imperial politics and helped to prevent rebellion and riots. Augustus sought to end the rampant political violence began with the Gracchi bothers nearly a century earlier.

Despite his obvious personal power, Augustus found it useful to maintain the facade of the Republic, along with republican values like thrift, honesty, bravery, and honor. He instituted strong moralistic laws that penalized (elite) young men who tried to avoid marriage and he celebrated the piety and loyalty of conservative married women. Even as he converted the government from a republic to a bureaucratic tool of his own will, he insisted on traditional republican beliefs and republican culture. This no doubt reflected his own conservative tastes, but it also eased the transition from republic to autocracy for the traditional Roman elites.

As Augustus’s powers grew, he received an altogether novel legal status, imperium majus, that was something like access to the extraordinary powers of a dictator under the Republic. Combined with his ongoing tribuneship and direct rule over the provinces in which most of the Roman army was garrisoned at the time, Augustus’s practical control of the Roman state was unchecked. As a whole, the legal categories used to explain and excuse the reality of Augustus’s vast powers worked well during his administration, but sometimes proved a major problem with later emperors because few were as competent as he had been. Subsequent emperors sometimes behaved as if the laws were truly irrelevant to their own conduct, and the formal relationship between emperor and law was never explicitly defined. Emperors who respected Roman laws and traditions won prestige and veneration for having done so, but there was never a formal legal challenge to imperial authority. Likewise, as the centuries went on and many emperors came to seize power through force, it was painfully apparent that the letter of the law was less important than the personal power of a given emperor in all too many cases.

This extraordinary power did not prompt resistance in large part because the practical reforms Augustus introduced were effective. He transformed the Senate and equestrian class into a real civil service to manage the enormous empire. He eliminated tax farming and replaced it with taxation through salaried officials. Within Rome, and other larger cities, Augustus established the first civil service, consisting of a series of prefecture or departments supervising, for example, the city watch, the grain supply, the water supply, the building of roads and bridges, tax collection, and the provisioning of the armies. Equestrians and freedmen were prominent in these prefectures and in provincial government, so they enthusiastically supported the Principate. Augustus also sought to rebuild the city of Rome back to its days of glory. He built monumental temples, including the enormous temple to Mars the Avenger in the center of the Forum, and expanded the Roman Forum in general. He even tried to improve sanitation by building aqueducts around the city to bring in fresh water.

The old Roman ruling class made its peace, though reluctantly, with Augustus. Some still looked back wistfully to the Late Republic (effectively destroyed by Caesar, though in decline as we saw since the Gracchi brothers) as a golden era of freedom. But most people in the Roman world welcomed and admired the Principate because Augustus and his successors brought peace and prosperity after a century of disasters under the late Republic. The Augustan period enjoyed affluence, especially in Italy; the other provinces slowly caught up with Italy by the 2nd century CE. Agriculture flourished with the end of civil war. Italian industries became leaders in exports. Italian glass bowls and windowpanes, iron arms, and tools, silver eating utensils, and candlesticks, and bronze statue sand pots circulated from Britain to central Asia.

And his reforms were not limited to Rome, they extended throughout much of the empire. He instituted a regular messenger/mail service. His forces attacked Ethiopia in retaliation for attacks on Egypt and he received ambassadors from India and Scythia (present-day Ukraine). In short, he supervised the consolidation of Roman power after the decades of civil war and struggle that preceded his takeover, and the large majority of Romans and Roman subjects alike were content with the demise of the Republic because of the improved stability Augustus’s reign represented. Only one major failure marred Augustus’s rule: three legions (perhaps as many as 20,000 soldiers) were destroyed in a gigantic ambush in the forests of Germany in 9 CE, halting any attempt to expand Roman power past the Rhine and Danube rivers. Despite that disaster, after Augustus’s death the senate voted to deify him: like his great-uncle Julius, he was now to be worshipped as a god.

The perennial problem of the Late Roman Republic had been land-hunger, which drove peasants into the arms of ambitious generals willing to help them. Augustus kept his troops happy by compensating 300,000 loyal veterans with land, money, or both, often in new overseas colonies. He made the rich pay for these services via new taxes. The result kept the peace, but many non-military in Italy remained poor, as of course did the huge number of slaves. But the urban poor of Rome enjoyed a more efficient system of free grain distribution under Augustus and a large increase in games and public entertainment-the imperial policy of “bread and circuses” designed to content the masses. Augustus also set up a major public works program, which provided jobs for the poor. He prided himself on having found Rome “a city of brick” and having left it a “city of marble.” Many benefited from this building program.

Finally, it was under Augustus that Roman law became a permanent fact. The first law school was opened in Rome under Augustus. Although various provincial legal systems remained in use, the international system of Roman law was also used widely in the provinces and would be the basis for law codes across Europe for centuries to come. He also made sure that only a few legal experts would guide the administration of justice by appointing a few distinguished jurists the exclusive right to issue legal opinions “on behalf of the princeps.”

One of the peculiar things about the Roman Republic is that its rise to power was in no way inevitable. No Roman leader had a “master plan” to dominate the Mediterranean world, and the Romans of 500 BCE would have been shocked to find Rome ruling over a gigantic territory a few centuries later. Likewise, the demise of the Republic was not inevitable. The class struggles and political rivalries that ultimately led to the rise of Caesar and then to the true transformation brought about by Octavian could have gone very differently. Perhaps the most important thing that Octavian could, and did, do was to recognize that the old system was no longer working the way it should, and he thus set about deliberately creating a new system in its place. For better or for worse, by the time of his death in 14 CE, Octavian had permanently dismantled the Republic and replaced it with the Roman Empire.