1 Chapter 1: The Origins of Civilization

What is “civilization”? In English, the word encompasses a wide variety of meanings, often implying a culture possessing some combination of learning, refinement, and political identity. As described in the introductory chapter, it is also a “loaded” term, replete with an implied division between civilization and its opposite, barbarism, with “civilized” people often eager to describe people who are of a different culture as being “uncivilized” in so many words. Fortunately, more practical and value-neutral definitions of the term also exist. Civilization as a historical phenomenon speaks to certain foundational technologies, most significantly agriculture, combined with a high degree of social specialization, technological progress (albeit of a very slow kind in the case of the pre-modern world), and cultural sophistication as expressed in art, learning, and spirituality.

In turn, the study of civilization has been the traditional focus of history, as an academic discipline, since the late nineteenth century. As academic fields became specialized over the course of the 1800s CE, history identified itself as the study of the past based on written artifacts. A sister field, archaeology, developed as the study of the past based on non-written artifacts (such as the remains of bodies in grave sites, surviving buildings, and tools). Thus, for practical reasons, the subject of “history” as a field of study begins with the invention of writing, something that began with the earliest civilization itself, that of the Fertile Crescent (described below). That being noted, history and archaeology remain closely intertwined, especially since so few written records remain from the remote past that most historians of the ancient world also perform archaeological research, and all archaeologists are also at least conversant with the relevant histories of their areas of study.

Hominids

Human beings are members of a species of hominid, which is the same biological classification that includes advanced apes like chimpanzees. The earliest hominid ancestor of humankind was called Australopithecus: a biological species of African hominid (note: hominid is the biological “family” that encompasses great apes – Australopithecus, as well as Homo Sapiens, are examples of biological “species” within that family) that evolved about 3.9 million years ago. Our very earliest ancestor is known as Australopithecus Afarensis. The most famous example and/or specimen of Australopithecus is known as “Lucy”, a partial skeleton discovered by Donald Johanson in 1974 in Ethiopia. He purportedly named the skeleton Lucy because Johanson and his colleagues repeatedly played the Beatles song “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” in celebration of the discovery.

Debate surrounds how Lucy and other Australopithecus moved, whether upright exclusively or on all fours. Anatomical studies point to both interpretations, but what is most important is that Australopithecus is the first known species to have spent time standing upright. Australopithecus was similar to present-day chimpanzees, loping across the ground on all fours rather than standing upright, with brains about one-third the size of the modern human brain. They were the first to develop tool-making technology, chipping obsidian (volcanic glass) to make knives. From Australopithecus, various other hominid species evolved, building on the genetic advantages of having a large brain and being able to craft simple tools.

One noteworthy descendent of Australopithecus was Homo Erectus, which gets its name from the fact that it was the first hominid to walk upright. Literally, Homo Erectus means “upright person.” It also benefited from a brain three-fourths the size of the modern human equivalent. Homo Erectus developed more advanced stone tool-making than had Australopithecus, and survived until about 200,000 years ago, by which time the earliest Homo sapiens – humans – had long since evolved alongside them.

Homo sapiens emerged in a form biologically identical to present-day humankind by about 300,000 years ago (fossil evidence frequently revises that number – the oldest known specimen was discovered in Morocco in 2017). Armed with their unparalleled craniums, Homo sapiens created sophisticated bone and stone implements, including weapons and tools, and also mastered the use of fire. They were thus able to hunt and protect themselves from animals that had far better natural weapons, and (through cooking) eat meat that would have been indigestible raw. Likewise, animal skins served as clothes and shelter, allowing them to exist in climates that they could not have settled otherwise.

Homo sapiens was split between two distinct types, physically different but able to interbreed, Neanderthals and Homo sapiens sapiens (the latter term means “the wisest man” in Greek). Neanderthals enjoyed a long period of existence between about 400,000 and 70,000 years ago, spreading from Africa to the Middle East and Europe. They were physically larger and stronger than Homo sapiens sapiens and were able to survive in colder conditions, which was a key asset during the long ice age that began around 100,000 years ago. Neanderthals congregated in small groups, apparently interacting only to exchange breeding partners or engage in warfare. Yet, they were some of the first humans to bury their dead usually with grave offerings (like flowers, animal bones, and flint) suggesting their capacity to mourn their losses and belief in some sort of an afterlife. They also engaged in warfare against one another using their stone tools and then developed ways to heal said wounds inflicted during combat.

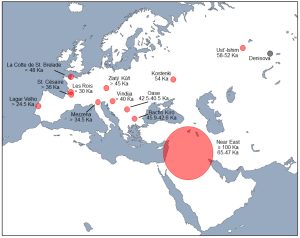

Homo sapiens sapiens were weaker and less able to deal with harsh conditions than Neanderthals, staying confined to Africa for thousands of years after Neanderthals had spread to other regions. They did enjoy some key advantages, however, having longer limbs and congregating in much larger groups of up to 100 individuals. A recent archaeological discovery (in 2019) demonstrated that Homo sapiens sapiens reached Europe and the Near East by 210,000 years ago, but that that wave of migrants subsequently vanished. As conditions warmed by about 70,000 years ago another wave of Homo sapiens sapiens spread to the Middle East and Europe and started both interbreeding with and – probably – slowly killing off the Neanderthals, who vanished soon after. By that time, Homo sapiens sapiens was already in the process of spreading all over the world. Yet to this day all or most individuals of European descent have approximately 2% Neanderthal DNA, demonstrating that extensive interbreeding took place.

Most massive global emigration was complete by about 40,000 years ago (with the exception of the Americas, which lasted until about 15,000 years ago). During an ice age, humans traveled overland on the Bering Land Bridge, a chunk of land that used to connect eastern Russia to Alaska, and arrived in the Americas. Later, very enterprising ancient humans built seagoing canoes and settled in many of the Pacific Islands. Thus, well before ancient humans had developed the essential technologies that are normally connotated with civilization, they had already accomplished transcontinental and transoceanic voyages and adapted to almost every climate on the planet.

Paleolithic Man in the Old Stone Age

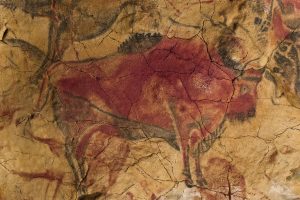

The absence of advanced technologies was not an impediment to the attempt to understand the world. One astonishing outgrowth of Homo sapiens sapiens’ brain power was the creation of both art and spirituality. Early Homo sapiens sapiens painted on the walls of caves, most famously in what is today southern France and Northern Spain, and at some point they also began the practice of burying the dead in prepared grave sites, indicating that they believed that the spirit survived physical death. We can see through cave paintings, carvings, and notations made on bone that humans were thinking about their environments and their experiences, perhaps even contemplating how they could transform them. Caves were especially significant for the Paleolithic Man as they provided excellent shelter from the elements, even remaining warmer during winter and cooler during summer months. Hence the common moniker of “caveman”.

In addition to the art found in caves, many sculptures have been found including engravings on stone as well as ivory. But, likely the most famous sculpture is that of “Venus” (named after the Roman goddess of love) figurine carved from limestone. It is about 4 and ½ inches tall and was found in present day Austria. Some theorize, due to the exaggerated breasts and pubic area of the statue, that it was meant to symbolize or have some power regarding fertility. It is a bit similar to future statues of the Roman goddess Venus, of love and sex. Artifacts that have survived from prehistory clearly indicate that Homo sapiens sapiens was not only creating physical tools to prosper, but creating art and belief systems in an attempt to make sense of the world at a higher level than mere survival. Beyond their artistic innovations, Paleolithic man also developed much more complex tools including those made from polished bone in addition to the stone tools that give this time period its name. Bone needles have also been found suggesting sewing, probably of animal skins for clothing in the cooler climes.

The presence of both art and activity specific tools suggests that there was a division of labor and skills in Paleolithic society. More than likely men were in charge of hunting, while women foraged for fruits or nuts and labored in the “home.” Hunting, especially large animals like mammoths was a communal activity occupying the entire community, more than likely a clan or kin-ship group. Organization as large as a tribe may have existed, but Paleolithic societies were small out of necessity. Hunting and gathering did not support large or stable populations as groups moved according to season and access to food. Nonetheless even in these small groups there is evidence of hierarchies and social differentiation with some having higher status than others. This can best be seen in Paleolithic burials where some were buried with weapons, tools, beads, and other grave goods. Presence of grave goods also provides further evidence of religious beliefs and ideas of an afterlife. Grave goods have most often been found with deceased males, supporting the idea that Paleolithic societies were patriarchal, meaning that men held the majority of power.

The Neolithic Revolution

Human beings have existed all over the world for many thousands of years. Human civilization, however, has not. The word civilization is tied to the Greek word for city, along with words like “civil” and “civic.” The key element of the definition is the idea that a number of people come together in a group that is too large to consist only of an extended family network. Once that occurred other discoveries and developments, from writing to mathematics to organized religion, followed.

Up until that point in history, however, cities had not been possible because there was never enough food to sustain a large group that stayed in a single place for long. Ancient humans were hunter-gatherers. They followed herds of animals on the hunt and they gathered edible plants as well. The problem with the hunter-gatherer lifestyle, however, is that it is extremely precarious: there is never a significant surplus of caloric energy, that is, of food, and thus population levels among hunting-gathering people were generally static. There just was not enough food to sustain significant population growth.

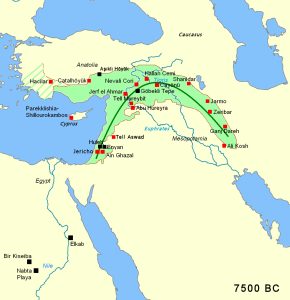

Starting around 9,500 BCE, humans in a handful of regions around the world discovered agriculture, that is, the deliberate cultivation of edible plants. People discovered that certain seeds could be planted and crops could be reliably grown. What brought about this discovery? First and foremost, climate change. Approximately 10-12 thousand years ago the long-term weather pattern of the Near east became milder and rainier prompting growth of abundant fields of wild cereal grains (wheat, hops, and barley for example). Similarly, research shows that increased rain in the Sahara desert in central Africa created lush grasslands or savannahs that attracted hunter-gathering nomads from the southern part of the continent.

With more available wild grains, food gathering became easier and a more abundant/regular supply of food led to higher fertility rates. As populations rose more people could dedicate their time to focusing on planting, eventually allowing for people to learn how to plant a portion of the seeds from one crop of grain to produce another. It is theorized that women, the gatherers, were the ones who discovered the secrets of agriculture while men were occupied with hunting. One of the earliest areas of domestication of plants and presence of agriculture is known as the Fertile Crescent located from present day Jordan to southern Iran. Concurrently agriculture was adopted in present day Egypt, along the Nile. Agriculture was developed in a few different places completely independently. According to archeological evidence, agriculture did not start in one place and then spread; it started in a few distinct areas and then spread from those areas, sometimes meeting in the middle. For example, agriculture developed independently in China by 5000 BCE, and of course agriculture in the Americas (starting in western South America) had nothing to do with its earlier invention in the Fertile Crescent.

Early agriculture, the kind of agriculture that made later advances in civilization possible, consisted of people simply planting seeds by hand or with shovels and picks. There were some important technological discoveries that took place over time that allowed much greater crop yields, however. They included:

- Crop rotation, which people discovered sometime around 8000 BCE. Crop rotation is the process of planting a different kind of crop in a field each year, then “rotating” to the next field in the next year. Every few years, a field is allowed to “lie fallow,” meaning nothing is planted and animals can graze on it. This process serves to return nutrients to the soil that would otherwise be leached out by successive years of planting, and it greatly increases yields overall.

- The metal plow, which people invented around 5000 BCE. Plows are hugely important; they opened up areas to cultivation that would be too rocky or the soil too hard to support crops normally.

- Irrigation, which happened in an organized fashion sometime around the same time in Mesopotamia.

Sometime after the development of agriculture, people in the same regions began to domesticate animals. The first domesticated animals were dogs, followed quickly by cattle, goats, sheep, etc. Humans began keeping herds of cattle, pigs, sheep, and goats in controlled conditions, defending them from predators, and eating them and using their hides. It is impossible to overstate how important these changes were. Even fairly primitive agriculture can produce fifty times more caloric energy than hunting and gathering does. The very basis of human life is how much energy we can derive from food; with agriculture and animal domestication, it was possible for families to grow much larger and overall population levels to rise dramatically. These larger populations became sedentary in order to be able to harvest their crops at the correct time, and once harvested, to protect their stores of grain. Hence, cities began to form.

Civilization first arose in present day Iraq in the valley between the Tigris and the Euphrates Rivers, or Mesopotamia (between the rivers in Greek). Shortly thereafter civilization began in the valley of the Nile River in present day Egypt. They did develop independently, but likely borrowed some things from one another. But why the Mesopotamia and Egypt first? The short answer is geography. Both valleys have alluvial land, meaning relatively flat (spacious areas perfect for growing cities) and fertile soil deposited by nearby rivers. These same rivers also flooded regularly, providing both water and new supplies of fertile riverine soil. This is especially true for Egypt, less so for Mesopotamia where the river flooding of the Tigris and Euphrates could be erratic. This led to the advent of irrigation and drainage using channels, dikes, or dams to control the floodwaters and improve the fertility of the land. Mesopotamia also regularly experiences extreme heat and scorching winds. This quasi-hostile environment may very well have inspired the cooperation needed to begin civilization. The canals and irrigation systems necessary to prevent flooding and provide water for crops required constant maintenance by a large skilled group of workers. This promoted the growth of centralized authority in Mesopotamian cities. Recent archaeological evidence suggests other motives, however, including the need for protection from rival groups and access to natural resources that were concentrated in a specific area.

Of the areas in which agriculture developed, the Fertile Crescent enjoyed significant advantages. Many nutritious staple crops like wheat and barley grew naturally in the region. Several of the key animal species that were first domesticated by humans were also native to the region, including goats, sheep, and cows. The region was also much more temperate and fertile than it is today, and the transition from hunting and gathering to large-scale farming was possible in Mesopotamia in a way that it was not in most other regions of the ancient world.

The First Cities

The food surplus that agriculture made possible in the Fertile Crescent eventually led to the emergence of the first large settlements. Some of the earliest that were large enough to quality as towns or even small cities were Jericho in Palestine, which existed by about 8000 BCE, and Çatal Höyük in Turkey, which existed by about 7500 BCE. There were certainly many others in the Fertile Crescent, but due to their antiquity the remains of only a few – Jericho and Çatal Höyük most importantly – have survived to be studied by archaeologists.

In 9,000 BCE Jericho was a very small village, but by 7,000 BCE it had grown to be a town surrounded by massive walls 10 feet thick and 13 or more feet high. The walls enclosed an area of about 10 acres. Within these walls up to 2,000 people lived, a large population at that time. But why the walls? As agriculture made people richer (surplus of food leading to further specialization of labor) they needed to protect their goods and settlements. Unfortunately, the accumulation of wealth also led to war and competition as other towns the size of Jericho, or bigger, began to pop up across Mesopotamia by 6,000 BCE. Here archaeologists have found artifacts such as woven fabrics, obsidian mirrors, and even makeup applicators. There is also evidence of long distance trade between villages in pottery and tools. Artwork shows men wearing loincloths and headdresses and women wearing pants and halter tops, with both sexes wearing jewelry.

Nearly concurrent with Jericho, was Çatal Höyük, a city established in 7400 BCE, in south central Turkey, in a marshland populated by a variety of fishes and birds. Farmlands and domestic livestock were cultivated in drier plains nearby. Within one thousand years, the city’s population more than doubled to a population of up to eight thousand. Religious rituals and burial traditions became more complex as art and sculpture evolved in the town as the population grew.

The wealth and success of Neolithic cities were based on access to natural resources. Çatal Höyük was built on a site that had a large deposit of obsidian (also called volcanic glass). Obsidian could be chipped to create extremely sharp tools and weapons. Tools made from Çatal Höyük’s obsidian have been discovered by archaeologists hundreds of miles from Çatal Höyük itself; thus, it is clear that Çatal Höyük was already part of long-distance trade networks, trading obsidian for other goods with other towns and villages. In essence, Çatal Höyük’s trade in obsidian proves that specialized manufacturing (in this case, of obsidian tools) and trade networks have been around since the dawn of civilization itself.

From the remains of Çatal Höyük it becomes possible to piece together certain facts about ancient societies on the cusp of civilization. First, it is clear that the earliest settlements (already) had significant social divisions. Hunter-gatherer societies have very few social divisions; there may be chiefs and shamans, but all members of the group are roughly equal in social power. One of the traits of civilization is the increasing complexity of social divisions, and with them, of social hierarchy. In Çatal Höyük, tombs have revealed that some people were buried with jewelry and weapons, while others were buried with practically nothing. It is very clear that even thousands of years ago, there were already major divisions between rich and poor.

In turn, the social divisions seen in Çatal Höyük’s graves reveal another key aspect of civilization: specialization. Social divisions themselves are only possible when there is a food surplus. If everyone has to work all the time to get enough food, there is little time left over for anyone to specialize in other activities. The reason that hunter-gatherer societies produce little in the way of scholarship or technology is that they do not have the resources for people to specialize in those areas. When agriculture made a food surplus possible for the first time in history, however, not everyone had to work on getting enough food, and soon, certain people managed to lay claim to new areas of expertise. Even in a settlement as ancient as Çatal Höyük, there were craftsmen, builders, and perhaps most interestingly, priests. In the ruins of the settlement archaeologists have found dozens of shrines to ancient gods and evidence of there being a priesthood.

The existence of a priesthood and organized worship in Çatal Höyük is striking, because it means that people were trying in a systematic way to understand how the world worked. In turn, priests were probably the world’s first intellectuals, people who use their minds for a living. Priests probably directed the efforts to build irrigation systems and made the decisions about building and rebuilding the town since they had a monopoly on explaining the larger forces at work in human life. Especially in a period like the ancient past when natural forces – forces like floods and disease – were vastly more powerful than the ability of humans to control them, priests were the only people who could offer an explanation.

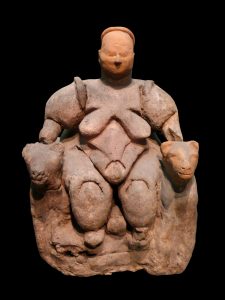

Not just in Mesopotamia, but all around the ancient world, there is significant evidence of religious belief systems centered on two major themes: fertility and death. One example of this are the “Venus figurines” depicting pregnant women with exaggerated physical features. Similar figures can be seen from all over the ancient Middle East and Europe, demonstrating that ancient peoples hoped to shape the forces that were most important to them. Early religions hoped to ensure fertility and stave off the many natural disasters that ancient peoples had no control over.

A “Venus” of Çatalhöyük, flanked by large felines, Museum of Anatolian Civilizations, Ankara, Turkey, c. 6000 BC https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%87atalh%C3%B6y%C3%BCk

The earliest surviving work of literature in the world, the Mesopotamian story known as the Epic of Gilgamesh, was focused on the theme of human mortality. Ancient peoples already sensed that human beings were in the process of accomplishing things that had never been accomplished before, namely the construction of large settlements, the creation of new technologies, and the invention of organized religions, and yet they also sensed that the human experience could be fraught with misery, despair, and what seemed like totally unfair and arbitrary disasters. And, as the Epic of Gilgamesh demonstrates, ancient peoples were well aware that no matter how great the accomplishments of a person during life, that person would inevitably die. That concern – the challenge of making sense of human existence in the face of death – is sometimes referred to by philosophers “the human condition,” and it is one that ancient peoples grappled with in their religious systems.

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia, on the eastern end of the Fertile Crescent, was the cradle of Western Civilization. It has the distinction of being the very first place on earth in which the development of agriculture led to the emergence of the essential technologies of civilization. Many of the great scientific advances to follow, including mathematics, astronomy, and engineering, along with political networks and forms of organization like kingdoms, empires, and bureaucracy all originated in Mesopotamia. This included the mastering of the technology of making bronze (an alloy of copper and tin) frequently replacing stone for everyday use in cookware and weaponry.

Mesopotamia is a region in present-day Iraq. The word Mesopotamia is Greek, meaning “between the rivers,” and it refers to the area between the Tigris and Euphrates, two of the most important waterways in the ancient world. It is no coincidence that it was here that civilization was born: like nearby Egypt and the Nile river, early agriculture relied on a regular supply of water in a highly fertile region. The ancient Mesopotamians had everything they needed for agriculture, they just had to figure out how to cultivate cereals and grains and how to manage the sudden floods of both rivers.

Mesopotamia’s climate was much more temperate and fertile than it is today. There is a great deal of evidence (e.g. in ancient art, in archeological discoveries of ancient settlements, etc.) that Mesopotamia was once a grassland that could support both large herds of animals and abundant crops. Thus, between the water provided by the rivers and their tributaries, the temperate climate, and the prevalence of the plant and animal species in the area that were candidates for domestication, Mesopotamia was better suited to agriculture than practically any other region on the planet.

While the Tigris and Euphrates provided abundant water, they were highly unpredictable and given to periodic flooding. The southern region of Mesopotamia, Sumer, has an elevation decline of only 50 meters over about 500 kilometers of distance, meaning the riverbeds of both rivers would have shifted and spread out over the plains in the annual floods. Over time, the inhabitants of villages realized that they needed to work together to build larger-scale levees, canals, and dikes to protect against the floods. One theory regarding the origins of large-scale settlements is that, when enough villages got together to work on these hydrological systems, they needed some kind of leadership to direct the efforts, leading to systems of governance and administration. Thus, the earliest cities in the world may have been born not just out of agriculture, but out of the need to manage the natural resource of water.

The first settlements that straddled the line between “towns” and real “cities” existed around 4000 BCE, but a truly urban society in Mesopotamia was in place closer to 3000 BCE, wherein a few dozen city-states managed the waters of the Tigris and Euphrates. A note on the chronology: the town of Çatal Höyük discussed above existed over four thousand years before the first great cities in Mesopotamia. It is important to bear this in mind, because when considering ancient history (in this case, in a short chapter of a textbook), it can seem like it all happened quite rapidly, that people discovered agriculture and soon they were building massive cities and developing advanced technology. That simply was not the case: compared to the hundreds of thousands of years preceding the discovery of agriculture, things moved “quickly,” but from a modern perspective, it took a very long time for things to change.

One compelling theory about the period between the invention of agriculture and the emergence of large cities (again, between about 8,000 BCE and 4000 BCE) is that a hybrid lifestyle of farming and gathering appears to have been very common in the large wetlands along the banks of the Euphrates and Tigris. Given the richness of dietary options in the region at the time, people lived in small communities for millenia without feeling compelled to build larger settlements. Somehow, however, a regime eventually emerged that imposed a new form of social organization and hierarchy, introducing taxation, large-scale building projects, and unfree labor (i.e. both slavery and forms of indentured labor). In turn, this appears to have occurred in the areas that grew cereal grains like wheat and barley extensively, because cereal grains were easy to collect and store, making them easy to tax.

The result of these new hierarchies were the first true cities that emerged in the southern region of Sumer. There, the two rivers join in a large delta that flows into the Persian Gulf. Farther up the rivers, the northern region of Mesopotamia was known as Akkad. The division is both geographical and lingual: ancient Sumerian is not related to any modern language, but the Akkadian family of languages was Semitic, related to modern languages like Arabic and Hebrew. Urban civilization eventually flourished in both regions, starting in Sumer but quickly spreading north.

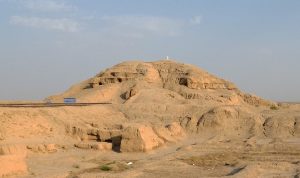

One early Sumerian city was Uruk, which was a large city by 3500 BCE. Uruk had about 50,000 people in the city itself and the surrounding region. It was a major center for long-distance trade, with its trade networks stretching all across the Middle East and as far east as the Indus river valley of India, with merchants relying on caravans of donkeys and the use of wheeled carts. Trade linked Mesopotamia and Anatolia (the region of present-day Turkey) as well. The economy of Uruk was what historians call “redistributive,” in which a central authority has the right to control all economic activity, essentially taxing all of it, and then re-distributing it as that authority sees fit. Practically speaking, this entailed the collection of foodstuffs and wealth by each city-state’s government, which then used it to “pay” (sometimes in daily allotments of food and beer) workers tasked with constructing walls, roads, temples, and palaces.

Political leaders in ancient Mesopotamia appear to have been drawn from both priesthoods and the warrior elite, with the two classes working closely together in governing the cities. Each Mesopotamian city was believed to be “owned” by a patron god, a deity that watched over it and would respond to prayers if they were properly made and accompanied by rituals and sacrifices. The priests of Uruk predicted the future and explained the present in terms of the will of the gods, and they claimed to be able to influence the gods through their rituals. They claimed all of the economic output of Uruk and its trade network because the city’s patron god “owned” the city, which justified the priesthood’s control. They did not only tax the wealth, the crops, and the goods of the subjects of Uruk, but they also had a right to demand labor, requiring the common people (i.e. almost everyone) to work on the irrigation systems, the temples, and the other major public buildings.

The first kings were almost certainly war leaders who led their city-states against rival city-states and foreign invaders. They soon ascended to positions of political power in their cities, working with the priesthood to maintain control over the common people. The Mesopotamian priesthood endorsed the idea that the gods had chosen the kings to rule, a belief that quickly bled over into the idea that the kings were at least in part divine themselves. Kings superseded priests as the rulers by about 3000 BCE, although in all cases kings were closely linked to the power of the priesthood. In fact, one of the earliest terms for “king” was ensis, meaning the representative of the god who “really” ruled the city. Thus, the typical early Mesopotamian city-state, right around 2500 BCE, was of a city-state engaged in long-distance trade, ruled by a king who worked closely with the city’s priesthood and who frequently made war against his neighbors.

Belief, Thought and Learning

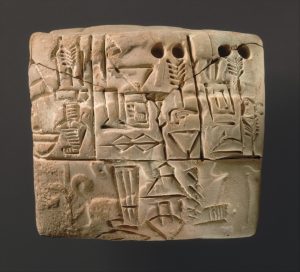

The capstone achievement of the Uruk period was the development of writing. Before writing Mesopotamian people used tiny clay or stone tokens to represent objects being counted or traded. By 3500 BCE there were over 250 different types of tokens in play making the system unwieldy enough for people to start using signs to indicate tokens. From there it was a short step to dispensing with the tokens and replacing the signs on a clay tablet by making indentations in the clay with a reed stylus, ie. Writing. New words were added through pictographs (pictures that stand for particular objects). In the centuries that followed its introduction, Mesopotamian writing became standardized into what scholars refer to as cuneiform from the Latin word for “wedge-shaped.” In its first centuries cuneiform was used mainly for economic and commercial records/transactions. For example this tablet here describes the distribution of beer made from barley for a group of laborers.

In fact quite a few cuneiform pictograms were used simply to describe beer, including how to brew the beverage. Beer was likely one of the first alcoholic beverages available to mankind due to spoiling of excess grains. Eventually though cuneiform was adapted to make brief records of offerings to the gods. But by 2350 cuneiform had evolved into a mixed system of about 600 signs, most of them phonetic (syllabic) with few pictograms. Cuneiform was used to record the spoken language, for poetry (including the famous epic poem of the king Gilgamesh), and for bookkeeping.

The first known author in history whose name and some of whose works survive was a Sumerian high priestess, Enheduanna. Daughter of the great conqueror Sargon of Akkad (described below), Enheduanna served as the high priestess of the goddess Innana and the god of the moon, Nanna, in the city of Ur after its conquest by Sargon’s forces. Enheduanna wrote a series of hymns to the gods that established her as the earliest poet in recorded history, praising Innana and, at one point, asking for the aid of the gods during a period of political turmoil.

Enheduanna did not record the first known work of prose, however, whose author or authors remain unknown. Remembered as the Epic of Gilgamesh, the earliest surviving work of literature, it is the best known of the surviving Mesopotamian stories. The Epic describes the adventures of a partly-divine king of the city of Uruk, Gilgamesh, who is joined by his friend Enkidu as they fight monsters, build great works, and celebrate their own power and greatness. Enkidu is punished by the gods for their arrogance and he dies. Gilgamesh, grief-stricken, goes in search of immortality when he realizes that he, too, will someday die. In the end, immortality is taken from him by a serpent, and humbled, he returns to Uruk a wiser, better king.

Like Enheduanna’s hymns, which reveal at times her own personality and concerns, the Epic of Gilgamesh is a fascinating story in that it speaks to a very sophisticated and recognizable set of issues: the qualities that make a good leader, human failings and frailty, the power and importance of friendship, and the unfairness of fate. Likewise, a central focus of the epic is Gilgamesh’s quest for immortality when he confronts the absurdity of death. Death’s seeming unfairness is a distinctly philosophical concern that demonstrates an advanced engagement with human nature and the human condition present in Mesopotamian society. It also reveals a great deal about Sumerian religious beliefs and conceptions of the afterlife.

The Mesopotamians believed that the gods were generally cruel, capricious, and easily offended. Humans had been created by the gods not to enjoy life, but to toil, and the gods would inflict pain and suffering on humans whenever they (the gods) were offended. A major element of the power of the priesthood in the Mesopotamian cities was the fact that the priests claimed to be able to soothe and assuage the gods, to prevent the gods from sending yet another devastating flood, epidemic, or plague of locusts. It is not too far off to say that the most important duty of Mesopotamian priests was to beg the gods for mercy.

The Sumerians were polytheistic (had many gods) and they believed that their gods were human in form. They, like the Greeks, thought their gods were much like regular human beings in that they could be wise at times and foolish at times. The big difference between humanity and the divine was that the gods possessed superpowers and were immortal. Some gods originated in nature, like Enlil the god of the sky and air or Utu the sun god. Others embodied human passions or notions about the afterlife like Inanna the goddess of love and war or Ereshkigal the goddess of the underworld.

One can see the importance of religion to the Sumerians in the very layout of their cities. At the very center of every Mesopotamian city was the main temple complex or the Ziggurat. These were stepped towers. It is likely that they began as simple raised terraces, but grew into seven-stepped structures. Some soared up to 10 stories high. They were not tombs like Egypt’s pyramids, but were “stairways” connecting humans and the gods. They were not just the centers of worship, but were also banks and workshops, with the priests overseeing the exchange of wealth and the production of crafts.

Even though Sumerians believed in a relationship between humans and gods, they had a very pessimistic view of divine will and the afterlife. Perhaps it was due to the difficult natural environment in which they lived, but for whatever reason the Mesopotamians regarded the gods with fear and awe. Though gods could communicate with humans when they chose, their language was mysterious and often unintelligible to humans. To understand the divine will, the Mesopotamians engaged in different kinds of divination or the interpretation of dreams. They would examine the entrails of slaughtered/sacrificed animals and study the stars. They hoped that by building temples, offering prayers, and conducting animal sacrifices they could appease the gods and discern what they wanted. Most people had little hope for the afterlife. They viewed it as a dark, shadowy existence. They thought that with a person’s last breath their spirit embarked on a long journey to the Netherworld, a place under the earth. The Netherwold was described as the “Land-of-no-return” and “the house wherein the dwellers are bereft of light, Where dust is their fare and clay their food, Where they see no light, residing in darkness.” The dead had to reside their permanently.

As mentioned previously one can see this fear of death and the gods in the epic poem Gilgamesh where the King goes on a vain quest for immortality. Interestingly the Epic contains stories that predate the biblical Eden and Flood narratives; at this point there is little doubt that the Israelites borrowed the narratives for the Hebrew Bible from Gilgamesh. The eleventh tablet of the Epic, describes the meeting of Gilgamesh with Utnapishtim. Like Noah in the Hebrew Bible, Utnapishtim had been forewarned of a plan by the gods to send a great flood. He built a boat and loaded it with all his precious possessions, his kith and kin, domesticated and wild animals and skilled craftsmen of every kind. Utnapishtim survived the flood for six days while mankind was destroyed, before landing on a mountain called Nimush. He released a dove and a swallow but they did not find dry land to rest on, and returned. Finally a raven that he released did not return, showing that the waters must have receded. An excerpt of the Epic, including the Flood Story is below.

However, by the end of the third millennium BC (2100s..) the Kings of Ur seem to have had more hope in the afterlife. We can see this in the fact that the rulers began to be buried with rich grave goods and even with their servants, pointing to human sacrifice. So the Sumerians must have had some notion that there would be a use for such things in the afterlife. Death was no longer a dark, barren existence.

Alongside the development of religious beliefs, science made major strides in Mesopotamian civilization. The Mesopotamians were the first great astronomers, accurately mapping the movement of the stars and recording them in astrological charts. They invented functional wagons and chariots and, as seen in the case of both ziggurats and irrigation systems, they were excellent engineers. They also invented the 360 degrees used to measure angles in geometry and they were the first to divide a system of timekeeping that used a 60-second minute. Finally, they developed a complex and accurate system of arithmetic that went on to form the basis of mathematics as it was used and understood throughout the ancient Mediterranean world.

At the same time, however, the Mesopotamians employed “magical” practices. The priests did not just conduct sacrifices to the gods, they practiced the art of divination: the practice of trying to predict the future. To them, magic and science were all aspects of the same pursuit, namely trying to learn about how the universe functioned so that human beings could influence it more effectively. From the perspective of the ancient Mesopotamians, there was little that distinguished religious and magical practices from “real” science in the modern sense. Their goals were the same, and the Mesopotamians actively experimented to develop both systems in tandem.

War and Empire in the Early Dynastic Period

By this period, 2800-2350 BCE, Mesopotamian cities often covered 1,000 acres, surrounded by 5 miles of walls, and held up to 50,000 residents. At this point there were as many as 30 independent city-states that all shared a common culture, commerce, and often fought one another. While they shared one language, religion, and literature, they still competed with one another usually over the scarcity of fresh water. Disputes over resources often led to conflict. By 2800 BCE political power of Sumerian city-states were largely in the hands of its Council of Elders (likely the wealthiest of land owners). It is possible that the Council shared power or at least consulted with a popular assembly, creating a very primitive democracy. However evidence to support this idea is ambiguous leaving it debatable if regular Sumerians actually took part in their government. This seems even more unlikely due to the evidence of both semi-free people and slaves in Sumerian society. Most Sumerians were likely partially free, meaning that they did not own their own land and were forced to work others’ land for at least part of the year as a form of taxation. They likely also worked to maintain the irrigation system. Then there was a population of slaves, ie. those who could be bought and sold. Most slaves came from abroad and had been taken as war booty. There were a few local slaves though, usually they ended up in slavery to pay off debts. Some parents even sold their daughters into slavery to escape debt.

By around 2700 the political scene began to shift. Chronic warfare began to demand a strong leader. Slowly Kings, and less frequently Queens, took over governance of city states. Usually the monarchs were warriors first and foremost. Sumerian Kings were not only responsible for war. They also supervised and sponsored irrigation works, raised fortification walls, restored temples, and built palaces. They also claimed to be the earthy representative of the gods, giving him general responsibility and power over his non-divine subjects. Sumerian kings controlled the justice system and made laws, at times harsh and at times to the ordinary peoples’ benefit. One of the earliest Sumerian kings was Gilgamesh of Uruk, also the hero of the famous epic poem from 2500 BCE. Most leaders were men and Sumer was a patriarchal society. Still women did have legal standing and rights under law, something they would lose in later Mesopotamian cultures. We even see the first recorded Queen in this period. Her name was Kish and she ruled the Sumerian city-state of Ku-baba around 2450 BCE

Mesopotamia represents the earliest indications of large-scale warfare. Mesopotamian cities always had walls – some of which were 30 feet high and 60 feet wide, essentially enormous piles of earth strengthened by brick. The evidence (based on pictures and inscriptions) suggests, however, that most soldiers were peasant conscripts with little or no armor and light weapons. In these circumstances, defense almost always won out over offense, making the actual conquest of foreign cities very difficult if not impossible, and hence while cities existed for thousands of years (again, from about 3500 BCE), there were no empires yet. Cities warred on one another for territory, resources, captives, and riches, but they rarely succeeded in conquering other cities outright. War was instead primarily about territorial raids and perhaps noble combats meant to demonstrate strength and power.

Over the course of the third millennium BCE, chariots became increasingly important in warfare. Early chariots were four-wheeled carts that were clumsy and hard to maneuver. They were still very effective against hapless peasants with spears, however, so it appears that when rival Mesopotamian city-states fought actual battles, they consisted largely of massed groups of chariots carrying archers who shot at each other. Noble charioteers and archers could win glory for their skill, even though these battles were probably not very lethal (compared to later forms of war, at any rate).

The first time that a single military leader managed to conquer and unite many of the Mesopotamian cities was in about 2340 BCE, when the king Sargon the Great, also known as Sargon of Akkad (father of Enheduanna, described above), conquered almost all of the major Mesopotamian cities and forged the world’s first true empire, in the process uniting the regions of Akkad and Sumer. His empire appears to have held together for about another century, until somewhere around 2200 BCE. Sargon also created the world’s first standing army, a group of soldiers employed by the state who did not have other jobs or duties. One inscription claims that “5,400 soldiers ate daily in his palace,” and there are pictures not only of soldiers, but of siege weapons and mining (digging under the walls of enemy fortifications to cause them to collapse).

The Akkadians were originally a seminomadic people who lived on the edge of the desert. Shepherds, they moved their flocks with the seasons. Their language, Akkadian, belongs to the Semitic group of languages, which also includes Arabic and Hebrew. Scholars formerly believed that the Akkadians came directly from the desert to conquer Sumer, but it is now known that they had begun settling in the northern cities of Mesopotamia by the end of the Uruk Period. This northern portion of Mesopotamia was known as Akkad. From this group emerged the commander of one of history’s first professional armies, Sargon, who conquered all of Mesopotamia (at least partially to acquire access to ore mines and already manufactured metal weapons, jewelry, etc.), and even extended his power/empire westward along the Euphrates and eastward into the Iranian Plateau.

Sargon himself was born an illegitimate child and was, at one point, a royal gardener who worked his way up in the palace, eventually seizing power in a coup. He boasted about his lowly origins and claimed to protect and represent the interests of common people and merchants. Sargon appointed governors in his conquered cities, and his whole empire was designed to extract wealth from all of its cities and farmlands and pump it back to the capital of Akkad, which he built somewhere near present-day Baghdad. While Sargon sought to control all economic resources in his empire, he also adopted many facets of Sumerian culture including Sumerian religion and cuneiform. While Akkadian became the official language of the empire, the Sumerian language survived. Poetry continued to be written in Sumerian. For example, Sargon’s daughter (who he appointed as the priestess at Ur and Uruk) continued to write poetry in Sumerian, including poems describing the union of the Akkadians and Sumerians. Sargon not only adopted Sumerian religion, but even used the Sumerians’ own religion to legitimize his rule. He claimed that he was the gods’ representative on earth and that is why his army had triumphed. Once he even paraded a defeated enemy in a halter before the temple and priests of Enlil proclaiming that Enlil was on his side.

The Akkadian empire also continued to grow under Sargon’s son and grandson, reaching its peak in 2220 BCE. At this point the Akkadians claimed that they reigned over “the peoples of all lands” or “the four quarters of the earth.” Soon after the Empire fell apart, but it is here that we first see the ideal of universal empire, something that future conquerors will continue to try for and lay claim to. In addition the conquest of new territories served to spread Sumerian culture to distant lands. By 2200 BCE the Akkadian empire broke up into a series of smaller successor states as a result of Civil War. These smaller states would eventually become the Babylonians and the Syrians. But first, the Sumerians actually reclaimed glory in the 3rd Dynasty of Ur (2112-2004 BCE), during which they called themselves the “kings of Sumer and Akkad,” so clearly the Akkadian Empire was not erased from Sumer’s history. Just as Sargon had, the king Ur-Nammu conquered and united most of the city-states of Mesopotamia. The most important historical legacy of the Ur III dynasty was its complex system of bureaucracy, which was more effective in governing the conquered cities than Sargon’s rule had been.

Bureaucracy (which literally means “rule by office”) is one of the most underappreciated phenomena in history, probably because the concept is not particularly exciting to most people. The fact remains that there is no more efficient way yet invented to manage large groups of people: it was viable to coordinate small groups through the personal control and influence of a few individuals, but as cities grew and empires formed, it became untenable to have everything boil down to personal relationships. An efficient bureaucracy, one in which the individual people who were part of it were less important than the system itself (i.e. its rules, its records, and its chain of command), was always essential in large political units.

The Ur III dynasty is an example of an early bureaucratic empire. Historians have more records of this dynasty than any other from this period of ancient Mesopotamia thanks to its focus on codifying its regulations. The kings of Ur III were very adept at playing off their civic and military leaders against each other, appointing generals to direct troops in other cities and making sure that each governor’s power relied on his loyalty to the king. The administration of the Ur III dynasty divided the empire into three distinct tax regions, and its tax bureaucracy collected wealth without alienating the conquered peoples as much as Sargon and his descendants had (despite its relative success, Ur III, too, eventually collapsed, although it was due to a foreign invasion rather than an internal revolt).

What all of these ancient empires had in common beyond a common culture was that they were very precarious. Their bureaucracies were not large enough or organized enough to manage large populations easily, and rebellions were frequent. There was also the constant threat from what surviving texts refer to as “bandits,” which in this context means the same thing as “barbarians.” To the north of Mesopotamia is the beginning of the great steppes of Central Asia, the source of limitless and almost nonstop invasions throughout ancient history. Nomads from the steppe regions were the first to domesticate horses, and for thousands of years only steppe peoples knew how to fight directly from horseback instead of using chariots. Thus, the rulers of the Mesopotamian city-states and empires all had to contend with policing their borders against a foe they could not pursue, while still maintaining control over their own cities. This precarity was responsible for the fact that these early empires were not especially long-lasting, and were unable to conquer territory outside of Mesopotamia itself. What came afterwards were the first early empires that, through a combination of governing techniques, beliefs, and technology, were able to grow much larger and more powerful.