2 Revenue Management Measurement

Competencies

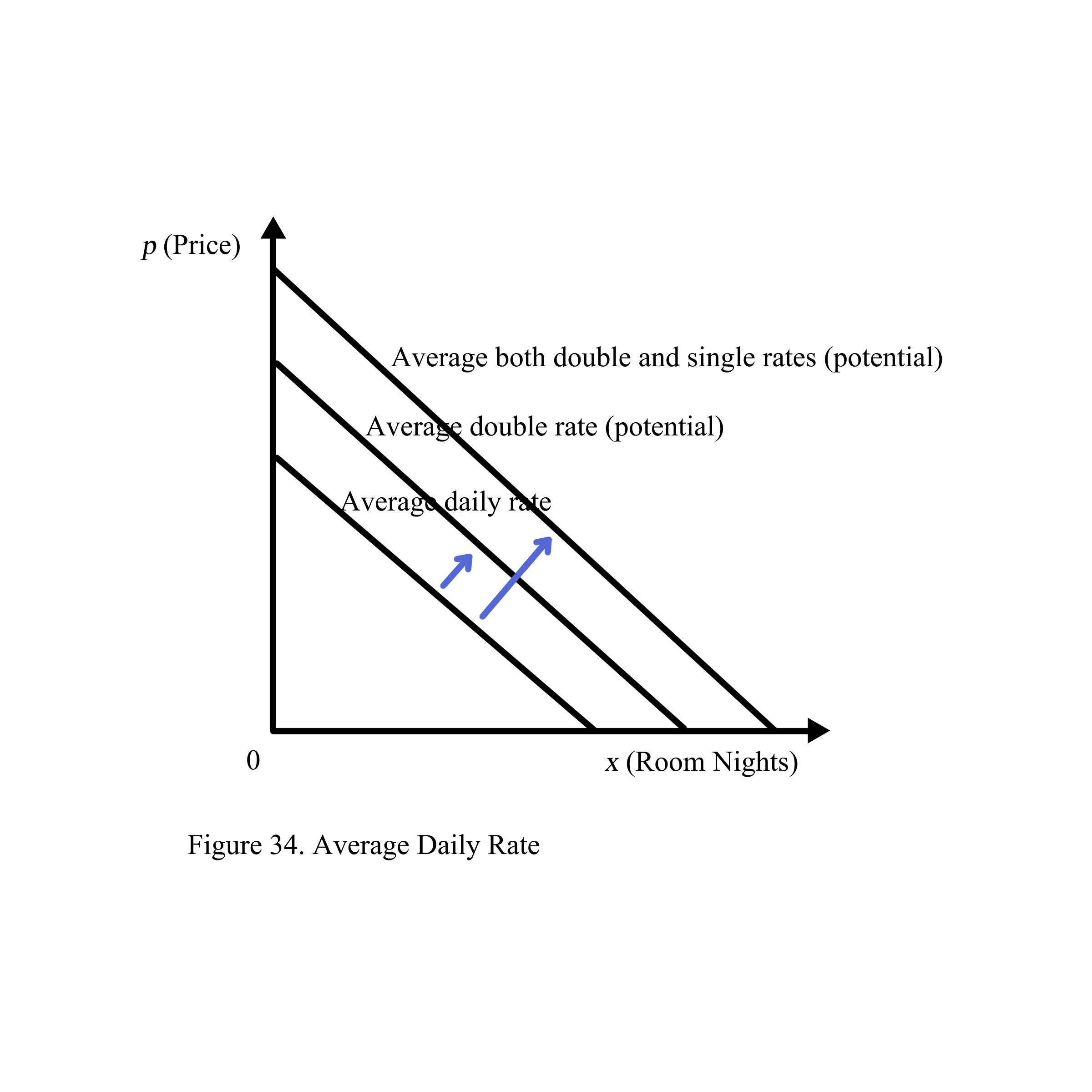

- Analyze Average Daily Rate (ADR), Occupancy (OCC), and Revenue per Available Room (RevPAR).

- Examine Competitive Set, Market share, and Index

- Measure Yield indices: Potential Average Double Rate and Potential Average Double and Single Rate.

Chapter 2 Outlines

1. ADR and RevPAR in Y axis and OCC in X axis.

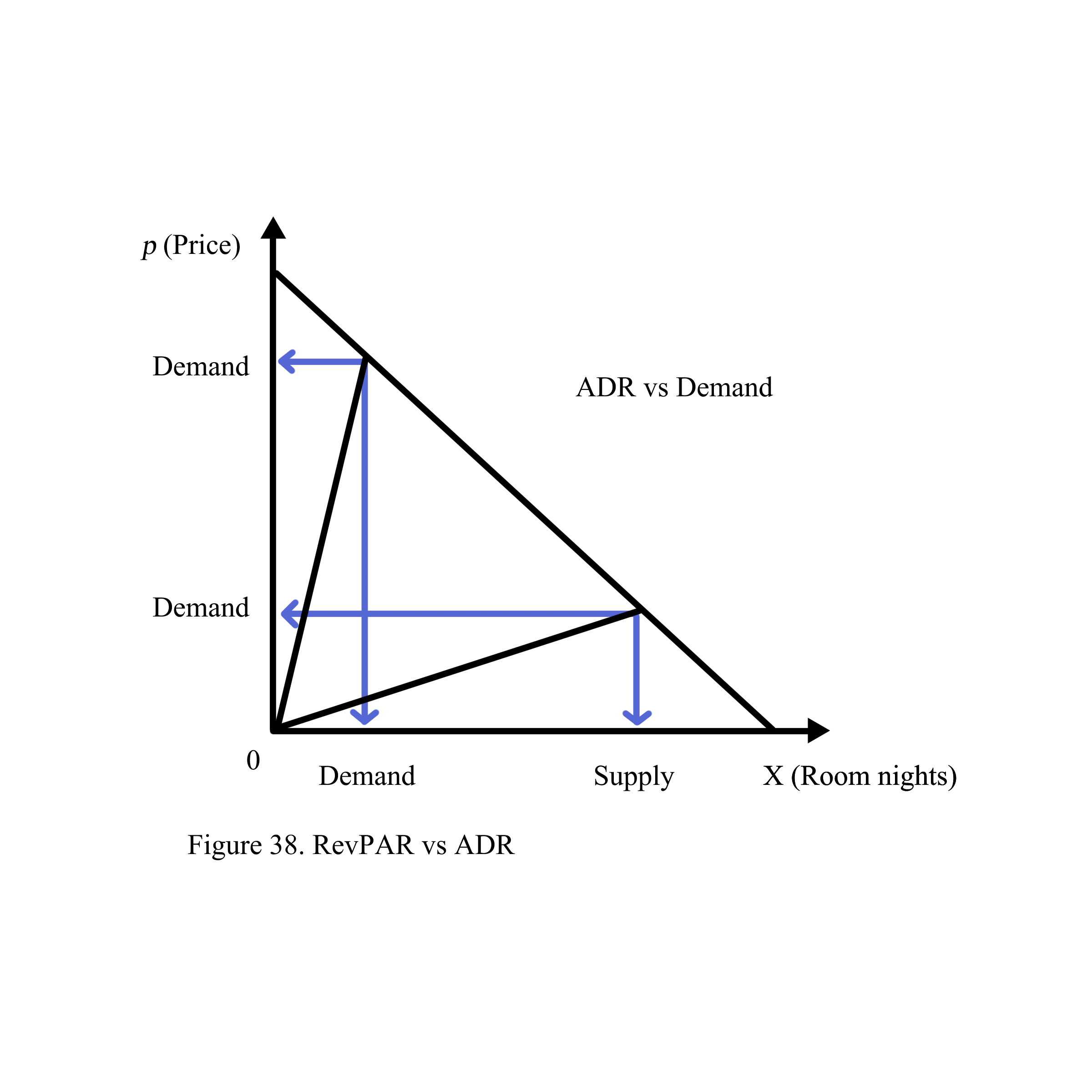

2. Revenue as two integrals: ADR vs. Demand and RevPAR vs. Supply

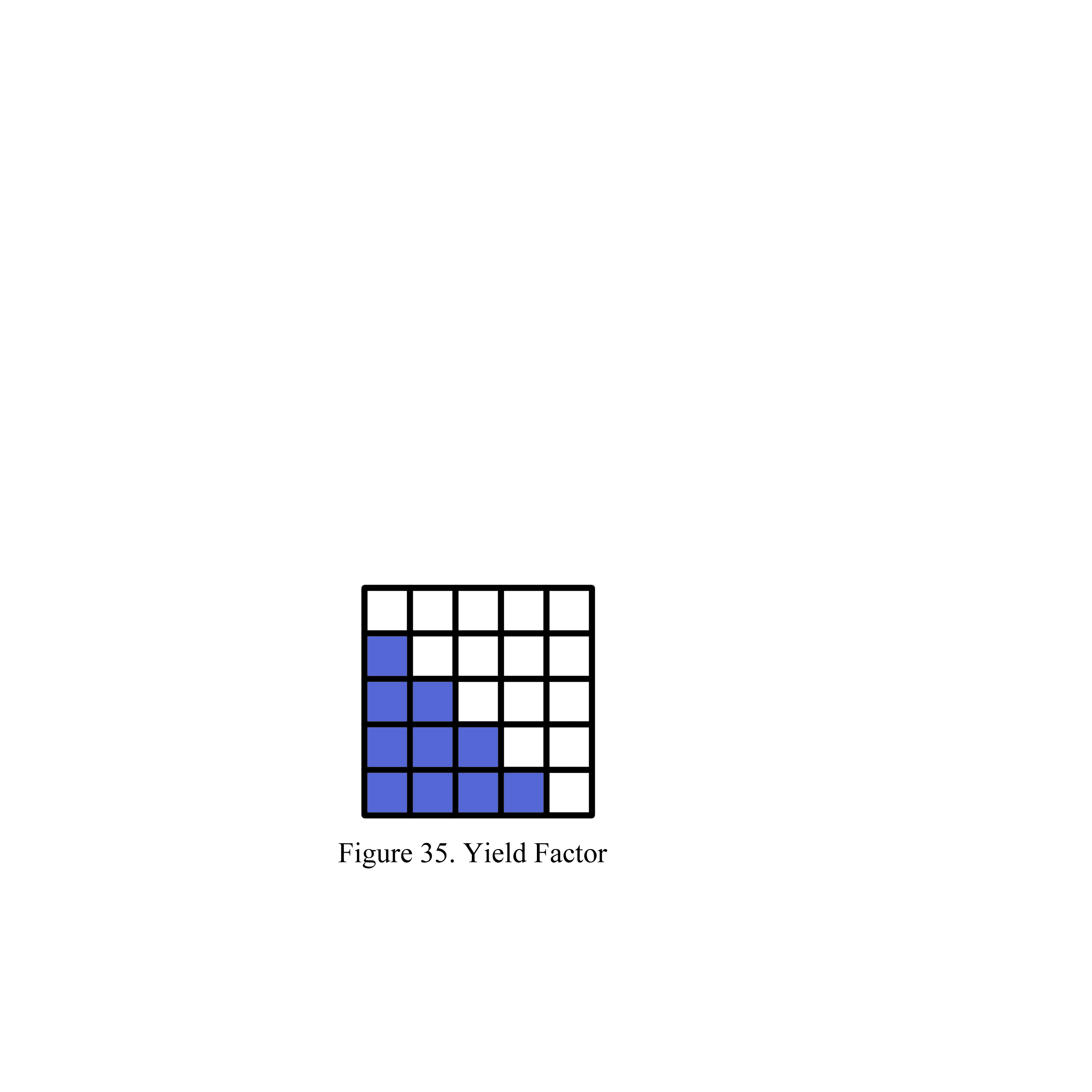

3. Yield as an integral of ADR and OCC

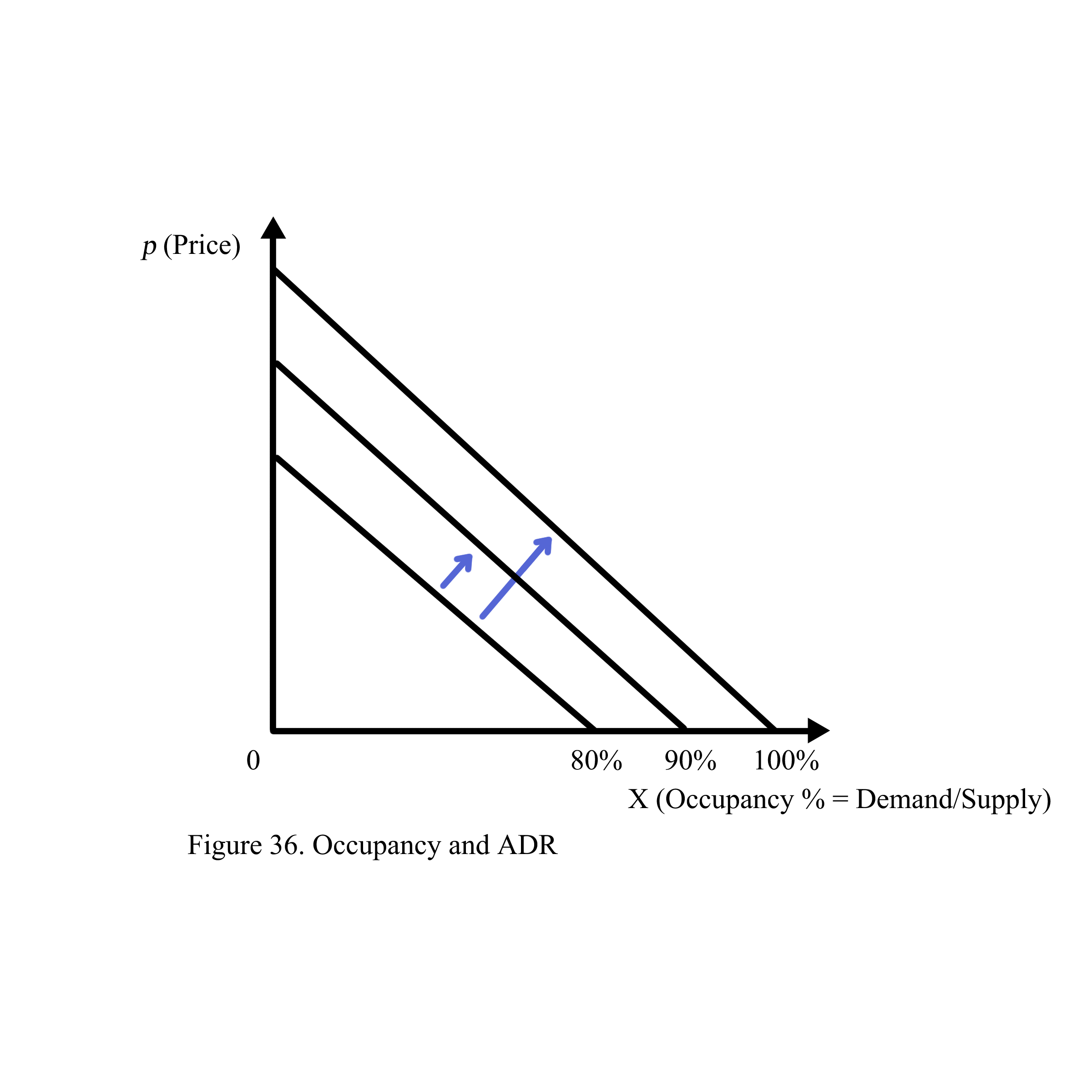

Occupancy is defined as the percentage of room nights sold relative to the number of room nights available, representing the ratio between realized demand and supply (see Figure 36).

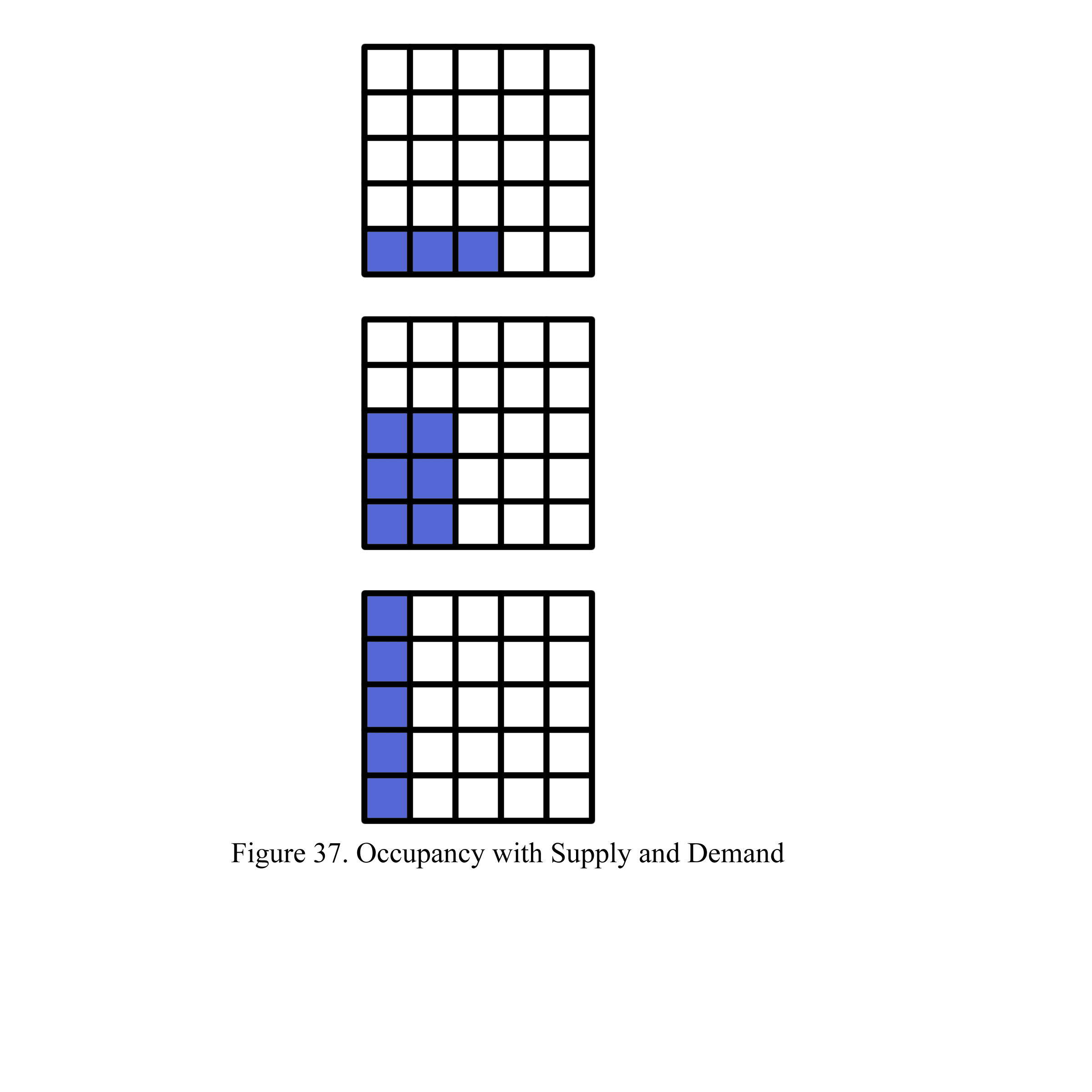

In the example shown, five rectangles represent five room nights (either 5 rooms for 1 night each or 1 room for 5 nights), indicating a total supply of 5 room nights regardless of pricing. If the hotel sold 3 of these room nights, the occupancy rate would be 60% (3/5).

Occupancy can vary by room type due to different pricing. For instance, Figure 37 illustrates that the occupancy rates are 60% for $100 rooms, 40% for $300 rooms, and 20% for $500 rooms. Overall, with three room types, the hotel’s combined occupancy rate is 40% (6/15 or the average of 120% divided by 3) (Figure 37)

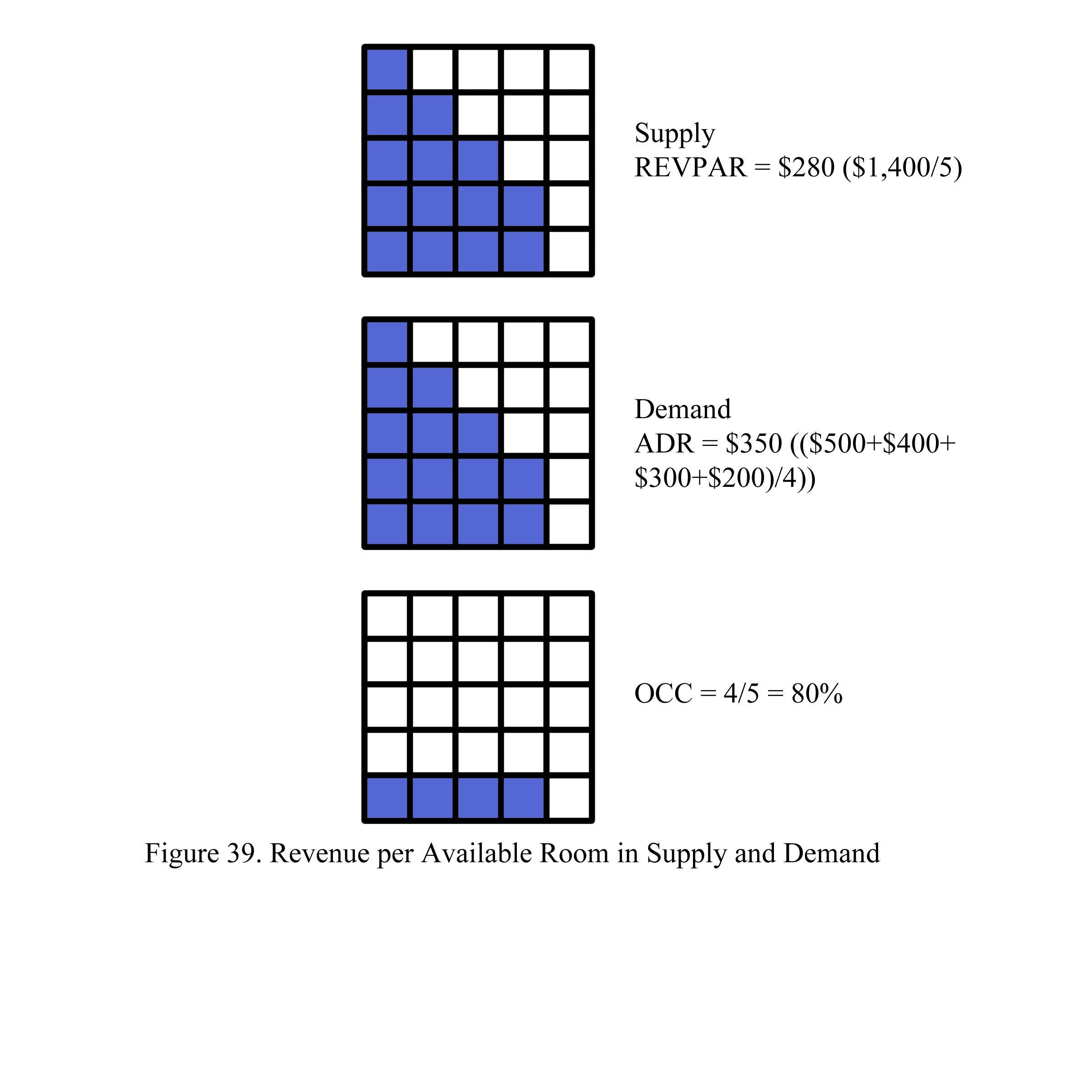

Revenue per Available Room (RevPAR) is defined as the average revenue generated from each room that is available. Unlike the Average Daily Rate (ADR), which reflects the revenue from rooms sold, RevPAR accounts for all available rooms. (See Figure 38).

The relationship between ADR and RevPAR can be expressed as follows: Occupancy * ADR = RevPAR (refer to Figure 39).

Key terms

Hotel Demand: The total number of room nights that guests want to book at a hotel during a specific period. It reflects how many rooms guests are seeking to reserve.

Example: If a hotel has 100 rooms and guests want to book 120 room nights, the demand is 120 room nights.

Hotel Supply: The total number of room nights available for booking at a hotel during a specific period. It represents the capacity of the hotel to accommodate guests.

Example: If a hotel has 100 rooms and is open for 30 days, the supply is 100 rooms * 30 nights = 3,000 room nights.

Revenue: The total income generated from room sales and other services offered by the hotel over a certain period.

Example: If a hotel sells 100 room nights at $200 each, the revenue is 100 * $200 = $20,000.

Average Daily Rate (ADR): The average revenue earned per occupied room per night. It is calculated by dividing the total room revenue by the number of rooms sold.

Calculation: ADR = Total Room Revenue / Number of Rooms Sold

Example: If a hotel earns $10,000 from 100 room nights, the ADR is $10,000 / 100 = $100.

Revenue per Available Room (RevPAR): The average revenue earned from each available room, regardless of whether it is occupied or not. It combines room revenue and occupancy into one metric.

Calculation: RevPAR = ADR * Occupancy Rate

Alternatively: RevPAR = Total Room Revenue / Total Room Nights Available

Example: If a hotel’s ADR is $100 and its occupancy rate is 60%, the RevPAR is $100 * 60% = $60. If the hotel has a total of 100 rooms available for 30 nights and earns $180,000 in room revenue, the RevPAR is $180,000 / (100 * 30) = $60.

Occupancy Rate (OCC): The percentage of available rooms that are actually sold or occupied. It measures how well the hotel is filling its available capacity.

Calculation: OCC = (Number of Rooms Sold / Number of Rooms Available) * 100

Example: If a hotel has 100 rooms available and sells 60 of them, the occupancy rate is (60 / 100) * 100 = 60%.

Percent Change: The percentage difference between two values over time. It is used to measure growth or decline in performance metrics like revenue, occupancy, ADR, or RevPAR.

Calculation: Percent Change = [(New Value – Old Value) / Old Value] * 100

Example: If a hotel’s ADR increased from $90 to $100, the percent change is [(100 – 90) / 90] * 100 = 11.1%.

Yield Management: a strategic pricing approach used to maximize revenue by dynamically adjusting prices based on demand, supply, and other market factors. The primary goal is to sell the right product to the right customer at the right time for the right price. This technique is especially prevalent in industries with fixed capacities, such as hotels, airlines, and car rental services.

Dynamic Pricing: Prices are adjusted in real-time based on current demand, supply conditions, and other factors. This can include increasing prices during peak demand periods and offering discounts during low demand periods.

Example: A hotel might charge higher rates during peak vacation seasons and lower rates during off-peak times.

Segmented Pricing: Different customer segments are offered different prices based on their willingness to pay, booking behaviors, or other characteristics.

Example: Business travelers may pay higher rates for flexibility and convenience, while leisure travelers might book at discounted rates well in advance.

Forecasting: Accurate predictions about future demand are crucial for effective yield management. Forecasting involves analyzing historical data, market trends, and booking patterns.

Example: An airline might use past travel data and current booking trends to predict future flight demand and adjust ticket prices accordingly.

Inventory Control: Managing the availability of rooms, seats, or units to maximize revenue. This can involve restricting the number of discounted rates available or controlling the release of inventory based on demand.

Example: A hotel might limit the number of discounted room rates available to ensure that higher-paying guests can still book at peak times.

Overbooking: Intentionally booking more reservations than the available inventory to compensate for expected cancellations or no-shows. This strategy helps to optimize occupancy rates.

Example: An airline might overbook flights by a small percentage, knowing that some passengers will not show up.

Revenue Optimization: The core aim of yield management is to maximize revenue by balancing the pricing and availability of inventory to achieve the highest possible revenue for the business.

Example: A hotel might use a combination of high pricing during busy periods and lower pricing during quieter periods to optimize overall revenue.

Benefits of Yield Management:

Increased Revenue: By adjusting prices based on demand and other factors, businesses can increase their overall revenue.

Improved Occupancy Rates: Effective management of inventory and pricing can lead to higher occupancy rates, even during periods of lower demand.

Enhanced Customer Segmentation: Allows for tailored pricing strategies to different customer groups, maximizing revenue from each segment.

Optimized Resource Utilization: Ensures that fixed resources, such as hotel rooms or airline seats, are used as efficiently as possible.

Challenges of Yield Management:

Complexity: Requires sophisticated systems and algorithms to analyze data and adjust prices in real-time.

Customer Perception: Dynamic pricing can sometimes lead to customer dissatisfaction if they feel they are not getting a fair deal.

Data Dependence: Relies heavily on accurate data and forecasts, which can be challenging to obtain and analyze.

Review Questions

- Draw graphs to measure achievement factors to indicate the most index yield.

- In terms of revenue, draw graphs to show that room occupancy is the most important for the hotel.

- Describe hotel supply in terms of yield management in a competitive set. Compare hotel supply elasticity with average daily rate (ADR).

- Draw graphs to show Y: ADR/ADRmax, X: Occ, Surface: Yield.