3 Tactics in Revenue Management

Competencies

- Understand Elasticity of consumer’s demand in cost allocation

- Identify Revenue Margin when Demand is inelastic or elastic in duration control

- Describe Hurdle Rate, Stay Through, Close to Arrival, Minimum Stay, Displacement

Chapter 3 Outlines

4.1. Inelastic demand and revenue margin with Y axis.

4.2. Elastic Demand and Revenue margin with X axis.

4.3. Hurdle rate at the joint between Revenue Margin and Average Cost

4.4. Sell Through

4.5. Close to Arrival

4.6. Minimum Stay

Inelastic Demand by unconstrained capacity

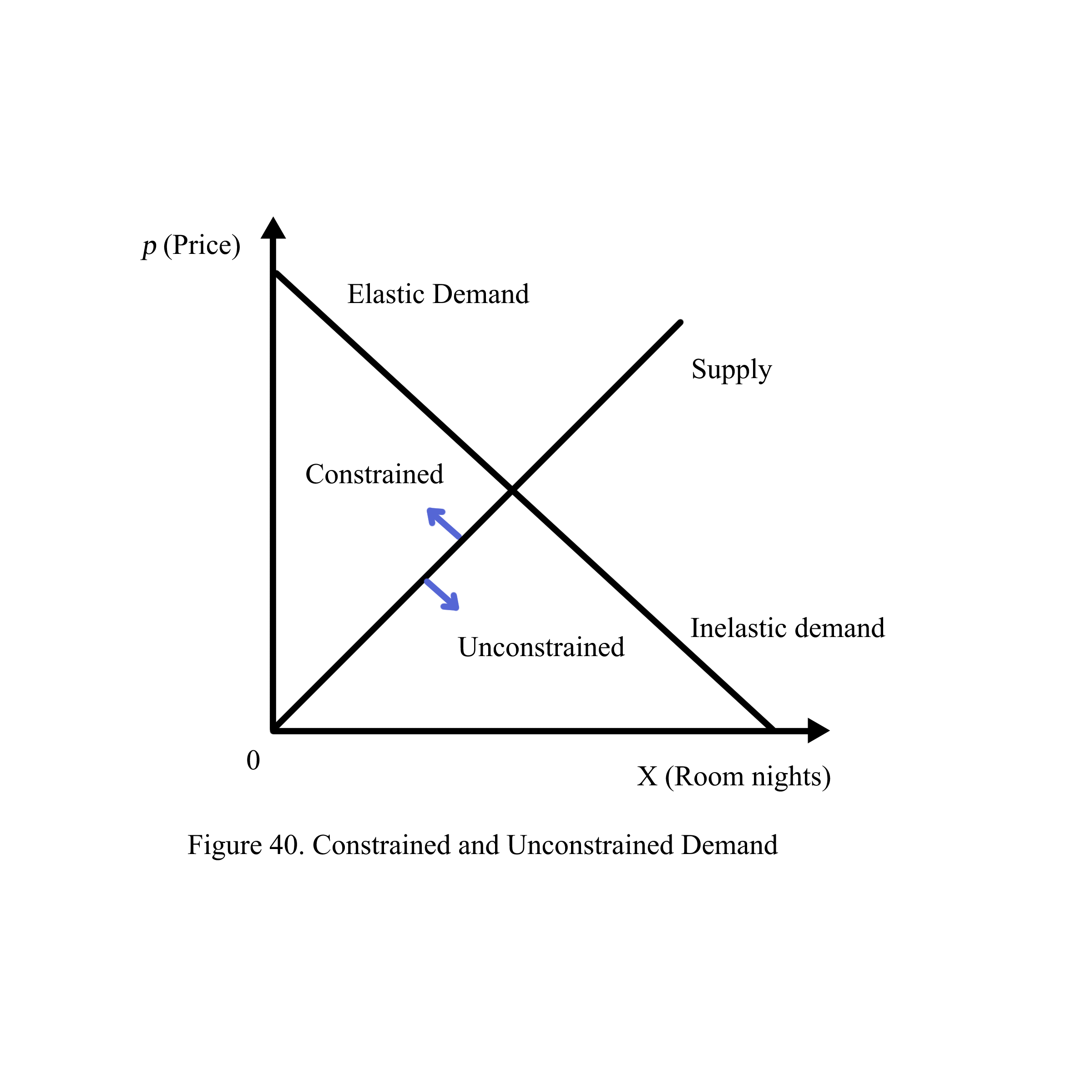

Demand reflects people’s needs, which can fluctuate—sometimes they need more, and other times less. When the need is higher, demand becomes inelastic. Conversely, when the need is lower, demand tends to be elastic. The two main factors influencing demand are price and income, which are interconnected and influence whether demand is more elastic (also known as unielastic) or more inelastic (referred to as Giffen).

When demand is inelastic or Giffen, it is described as unconstrained, whereas elastic or unielastic demand is termed constrained demand.

In the hospitality industry, seasonality plays a significant role alongside price and income in influencing demand. Seasonality refers to the variations in demand that occur due to factors such as weather patterns or cultural practices in a particular country. These factors can significantly impact when and how people travel, leading to shifts in demand throughout the year.

For instance, in regions with distinct seasonal changes, such as summer and winter, or during culturally significant holidays, the demand for accommodations may spike. This increase in demand during specific times of the year is often referred to as the high season. During these periods, the industry experiences what is known as constrained demand. Constrained demand occurs when the number of guests seeking accommodations exceeds the available capacity. A common example of this is during spring break for elementary, middle, and high school students, when many families take advantage of the school holidays to travel. This results in a surge in demand that hotels and other hospitality providers must manage.

Conversely, unconstrained demand refers to periods when the opposite is true—when there are fewer guests than the available accommodations can support. This typically occurs during off-peak times, such as when students are in the middle of their school term or during unfavorable weather conditions that discourage travel. During these times, the demand for hospitality services drops, leading to what is known as unconstrained demand. Understanding these fluctuations is crucial for the hospitality industry to effectively manage resources, set pricing strategies, and maximize occupancy rates throughout the year (Figure 40).

Elastic Demand by Constrained Capacity

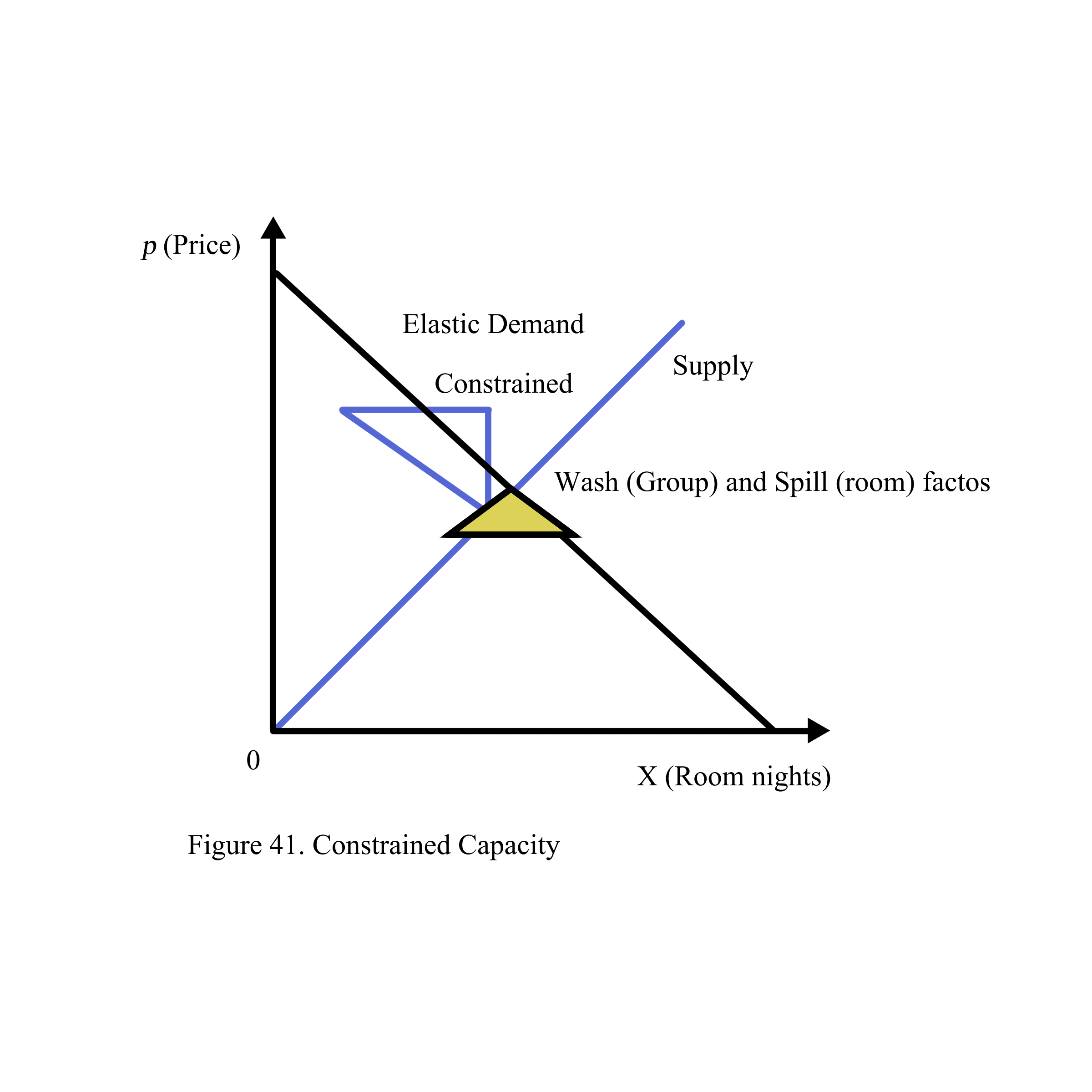

The above constrained capacity is from hotel suppliers. When a guest’s desire for certain services or accommodations exceeds their financial resources, making their demand highly elastic, it occurs the guest income constraints. In this context, elasticity refers to the sensitivity of demand to changes in price. When guests face income constraints, they are more likely to adjust their spending behavior, often opting for more affordable alternatives when prices rise.

For instance, during peak hotel seasons, when room rates are typically higher due to increased demand, guests with limited incomes may find it challenging to afford these higher-priced accommodations. As a result, their demand becomes elastic—they are more likely to seek out lower-cost alternatives, such as budget hotels, vacation rentals, or even postponing their trips until prices drop. This substitution effect illustrates how income constraints can lead to a shift in demand toward more affordable options when faced with higher prices.

In such scenarios, the hotel’s pricing strategy and the overall market conditions play a crucial role in influencing guest behavior. Hotels that cater to a broader range of income levels may be able to retain price-sensitive customers by offering discounts, promotions, or value-added services that appeal to those with constrained incomes. However, for guests whose income significantly limits their spending power, even small increases in price can lead to a significant decrease in demand, further emphasizing the elasticity of their demand.

This concept underscores the importance of understanding the income dynamics of a hotel’s target market. By recognizing the income constraints of potential guests, hotels can better tailor their offerings and pricing strategies to meet the needs of a diverse clientele, ultimately maximizing occupancy and revenue while accommodating guests across different income levels (Figure 41)

Duration constraints

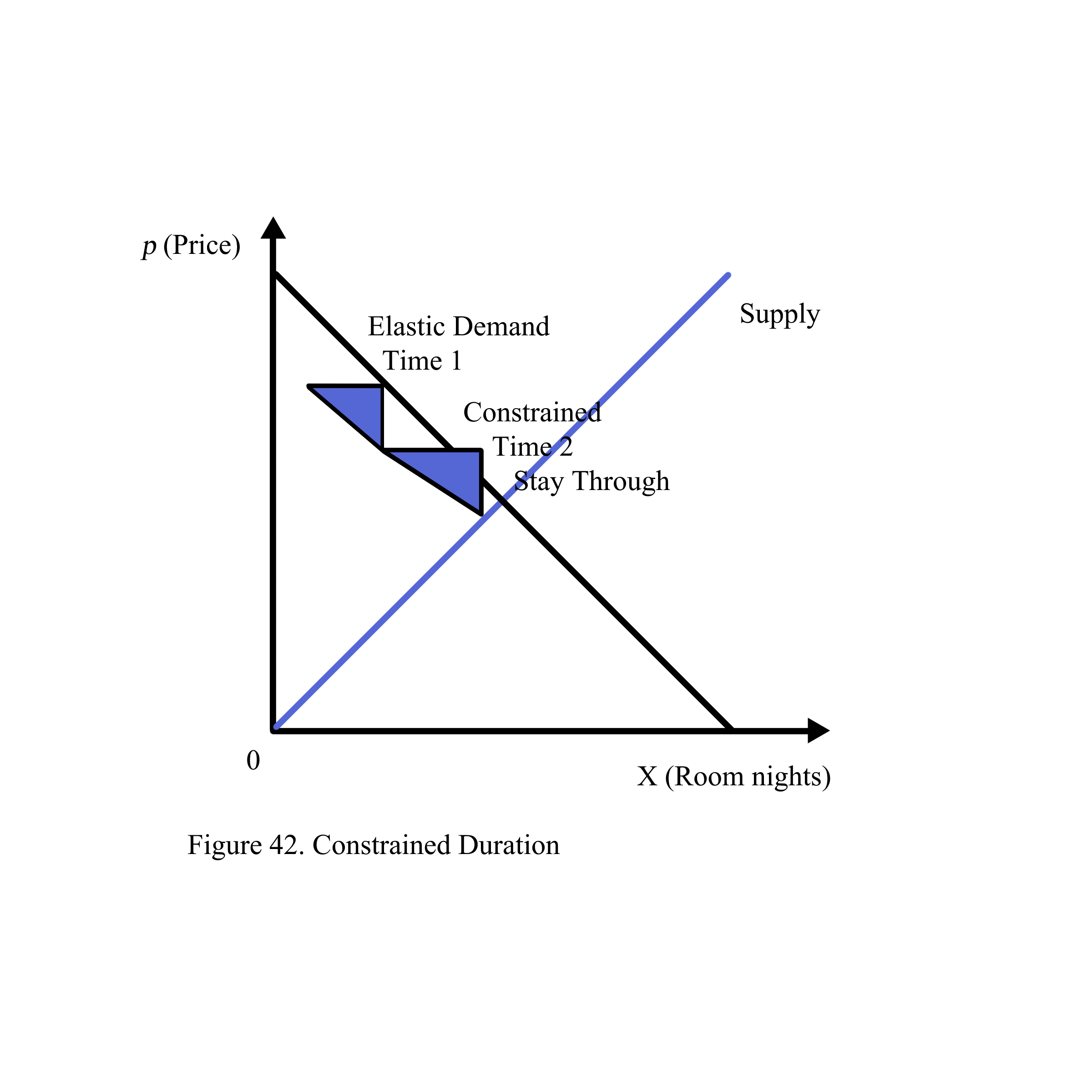

Duration constraints refer to the fluctuations in the number of customers seeking accommodations within a specific time period, often leading to peaks and troughs in demand for hotel rooms. These constraints arise when a large number of people, due to similar schedules or circumstances, are looking to stay at hotels during the same period. As a result, the demand for accommodations becomes concentrated within that timeframe, creating a high demand that can strain the available resources of the hotel.

A common example of a duration constraint is the summer break for students. During this period, many students and their families are on vacation, leading to a surge in demand for hotel rooms. Because so many people are traveling at the same time, hotels experience a significant increase in bookings. The concentrated demand during this period creates a situation where hotels may reach full capacity quickly, making it challenging for latecomers to find available rooms or affordable rates.

Duration constraints are not limited to student breaks; they can occur during any period when a large group of people simultaneously seeks accommodations. This could include holidays like Christmas or New Year’s, significant events like conferences or festivals, or even specific weekdays when business travelers are more likely to book rooms.

These constraints can have several implications for the hospitality industry. For one, hotels may adjust their pricing strategies during these periods, often raising rates to reflect the increased demand. This can lead to higher revenue but also creates the risk of pricing out certain segments of the market, such as budget-conscious travelers. Additionally, hotels may need to manage their resources carefully during these peak times to ensure they can provide the expected level of service despite the higher volume of guests.

For travelers, duration constraints mean that planning and booking accommodations well in advance is crucial, especially during peak periods. Those who delay may find that their options are limited or more expensive. Alternatively, travelers may choose to avoid these constrained periods altogether by planning their trips during off-peak times when demand is lower and more accommodations are available at better rates.

In summary, duration constraints refer to the variations in the number of customers seeking hotel accommodations during the same time period, often leading to spikes in demand. These constraints are driven by specific events or schedules, such as student summer breaks, and have significant implications for both hotels and travelers in terms of pricing, availability, and planning (Figure 42).

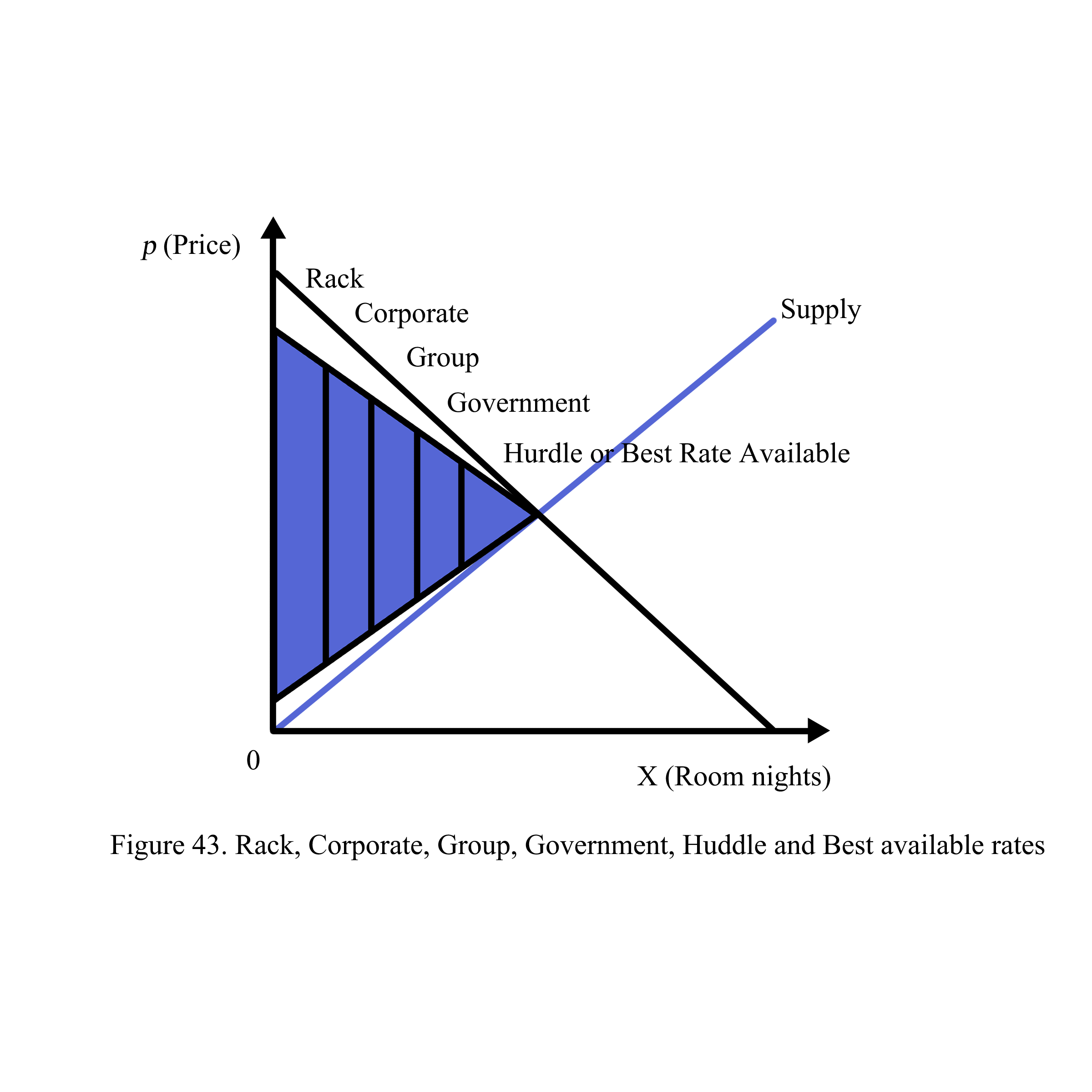

Rate Structure

Rate structures in the hospitality industry refer to the varying pricing strategies that hotels employ for rooms of the same brand or even the same room type. These differences in pricing are influenced by several factors, including the type of room, the quantity of rooms requested, the quality of the rooms, and the affiliations or relationships that guests might have with certain organizations. Understanding these rate structures is essential for both hotel management and guests, as it helps in optimizing occupancy and revenue while providing customers with pricing options that suit their needs.

One example of rate structure is the pricing differentiation based on the type of room. Even within the same hotel brand, different room categories—such as standard rooms, deluxe rooms, or suites—will be priced differently based on their size, view, amenities, and overall quality. For instance, a suite with a panoramic view and luxurious amenities will command a higher rate than a standard room with basic features. This allows hotels to cater to a broad spectrum of customers, from budget-conscious travelers to those seeking luxury experiences.

Another aspect of rate structure is the pricing variation based on the quantity of rooms requested. For example, a guest booking multiple rooms for a group or a large family may be offered a discounted rate compared to someone booking a single room. Similarly, corporate clients or organizations that regularly book rooms in bulk may receive special rates as part of a negotiated contract. These discounts are often used as incentives to encourage larger bookings and to build long-term relationships with corporate partners or group organizers.

Additionally, rate structures can also vary depending on the affiliations or memberships that a guest may have. For example, hotels might offer discounted rates to members of certain organizations, such as AAA, AARP, or military personnel. These special rates are a way to attract loyal customers and offer value to specific groups, enhancing the hotel’s appeal to a broader audience.

It is important to note that while demand fluctuations throughout the day might influence availability and occupancy, the actual rate for a room typically does not change based on the time of check-in. Instead, hotels adjust their pricing based on overall demand trends, room availability, seasonality, and market competition. For instance, during high-demand periods such as holidays or major events, room rates might increase, whereas during off-peak times, hotels may lower their rates to attract more guests.

In summary, rate structures in hotels refer to the strategic variations in pricing based on factors such as room type, quantity of rooms requested, quality, and organizational affiliations. These structures allow hotels to cater to different market segments, optimize revenue, and build customer loyalty by offering tailored pricing options that meet the diverse needs of their guests (Figure 43).

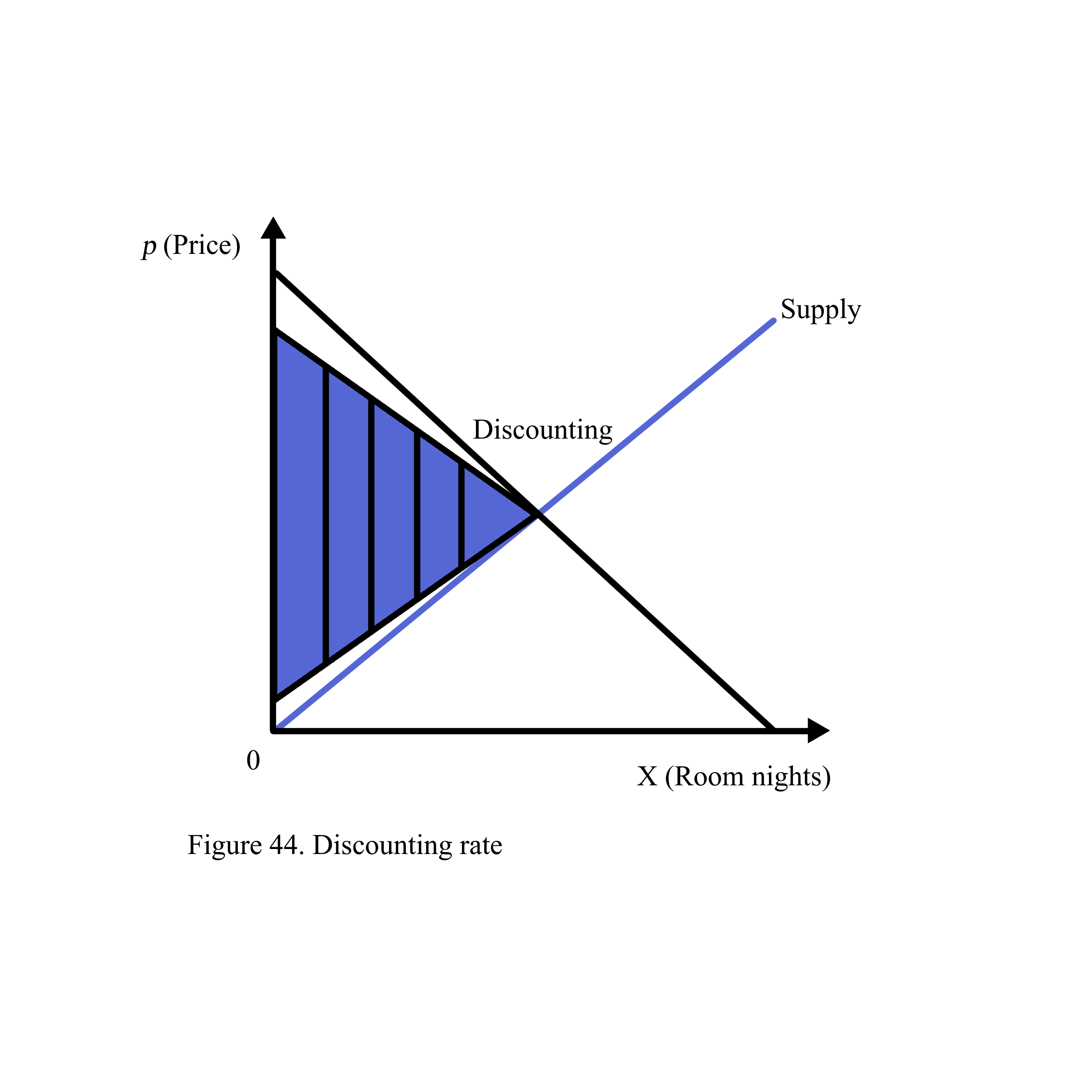

Tactical Discounting

Tactical discounting can be defined as the strategic practice of offering discounted rates to specific segments of the market that are particularly sensitive to price. The primary goal of tactical discounting is to increase occupancy rates by attracting more guests, particularly those who might otherwise be deterred by standard pricing. This approach is especially useful in filling rooms during off-peak times, boosting revenue during slow periods, or catering to certain groups who are likely to respond positively to discounted rates.

Tactical discounting often involves providing targeted discounts to groups such as military personnel, seniors, children, students, or members of certain organizations. These segments are typically more price-conscious and may have limited budgets, making them more responsive to offers that lower the cost of their stay. For example, a hotel might offer a 10% discount to active-duty military members and veterans as a way to honor their service and encourage them to choose that hotel over competitors. Similarly, seniors might receive a discounted rate as a gesture of appreciation, while families traveling with children could be offered reduced rates to make the stay more affordable.

This form of discounting is not just about lowering prices across the board but rather about using discounts strategically to appeal to specific customer segments. By offering these targeted discounts, hotels can fill rooms that might otherwise go vacant, thereby maximizing their occupancy and revenue potential without significantly impacting overall profitability. It also helps in building customer loyalty, as guests who benefit from these discounts are more likely to return in the future or recommend the hotel to others.

In addition to increasing occupancy, tactical discounting can serve as a marketing tool. For instance, promoting special discounts for seniors or military personnel can enhance a hotel’s reputation as a business that values and supports these groups. This can lead to positive word-of-mouth and brand loyalty, further driving bookings from these segments.

Tactical discounting also allows hotels to better manage their inventory. By offering discounts to price-sensitive segments, hotels can achieve a more balanced demand throughout the year. During periods of lower demand, these discounts can help attract guests who are specifically looking for affordable accommodations, thereby reducing the number of empty rooms. On the other hand, during peak seasons, these discounts can be adjusted or limited to maintain profitability while still rewarding loyal or targeted segments (Figure 44).

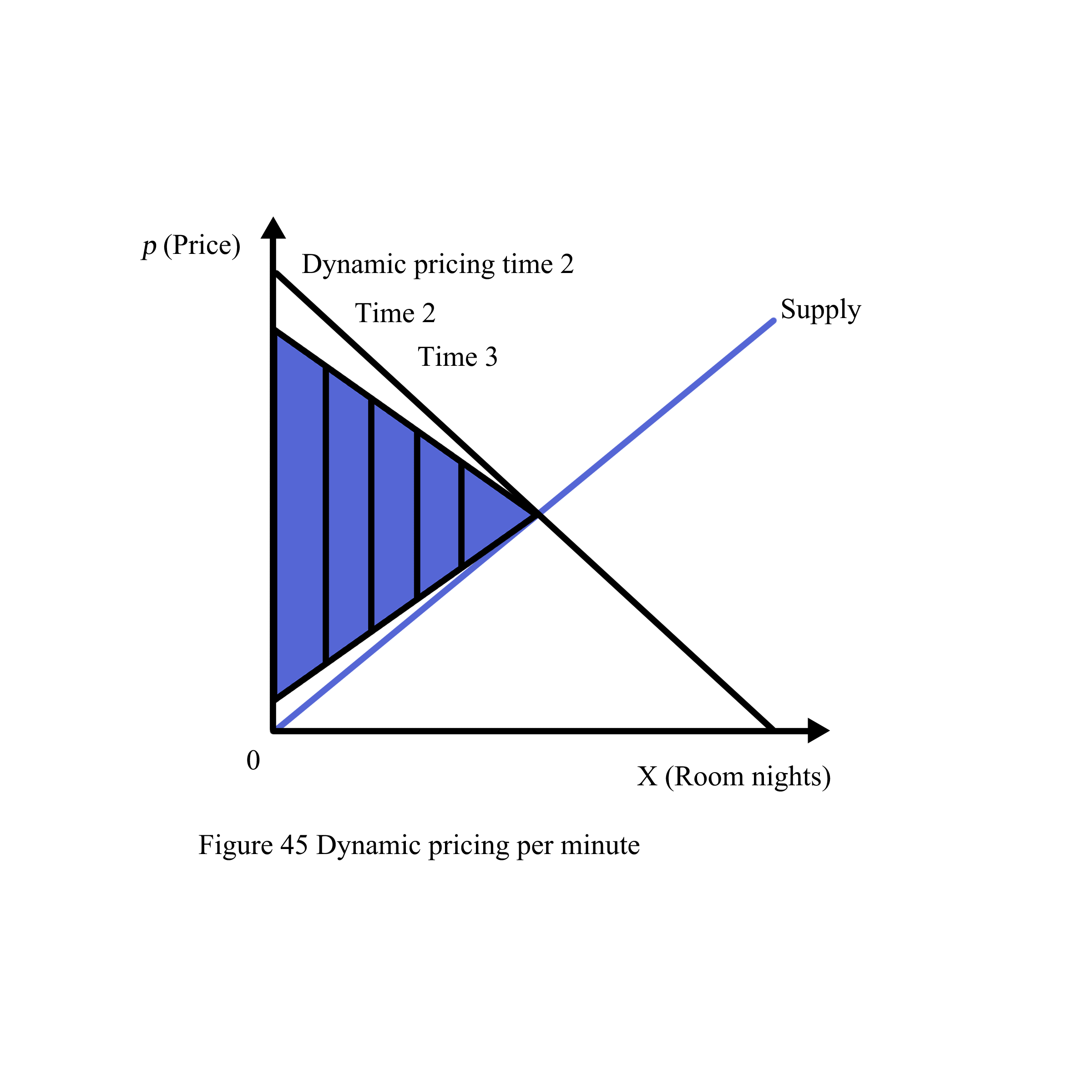

Dynamic Pricing

Dynamic pricing is a pricing strategy where the discount offered is based on a percentage off the current selling rate, rather than a fixed discounted rate. This approach allows businesses to adjust prices in real-time according to various factors, such as demand, time of day, or occupancy levels. Unlike tactical discounting, which typically offers discounts based on a guest’s social status or affiliation (e.g., military, senior, or student discounts), dynamic pricing focuses on offering discounts based on timing and market conditions.

For example, a hotel might implement dynamic pricing by offering a 40% discount to the first customers who check in during a specific time frame, such as early in the morning or late at night when the hotel has fewer guests. This strategy not only incentivizes early bookings but also helps the hotel manage its room occupancy more efficiently. By offering significant discounts during periods of lower demand, the hotel can attract more guests and increase its overall occupancy rate.

Similarly, a coffee shop might use dynamic pricing to encourage customers to visit during off-peak hours when business is slow. For instance, they could offer a discount to customers who come in during mid-afternoon or late evening, times when the shop typically sees fewer patrons. This approach helps the business balance customer flow throughout the day, filling seats and generating revenue during quieter periods.

Dynamic pricing is a flexible and responsive pricing strategy that allows businesses to optimize their revenue by adjusting prices based on real-time factors. It is particularly effective in industries like hospitality, retail, and food service, where demand can fluctuate significantly throughout the day, week, or season. By offering discounts that vary depending on the time or level of demand, businesses can maximize occupancy, boost sales during slow periods, and ultimately increase profitability.

In addition to driving sales during low-demand periods, dynamic pricing can also enhance customer satisfaction by providing value to price-sensitive customers who are willing to adjust their purchasing behavior to take advantage of discounts. This strategy can create a sense of urgency, encouraging customers to book or buy sooner rather than later, which helps businesses secure revenue early and manage inventory more effectively.

Moreover, dynamic pricing can be integrated with modern technology, such as online booking platforms or mobile apps, to automatically adjust prices based on real-time data. This allows businesses to implement dynamic pricing strategies seamlessly and efficiently, providing customers with up-to-date pricing information and ensuring that discounts are applied consistently.

In summary, dynamic pricing is a strategy where discounts are applied as a percentage off the current selling rate, and it differs from tactical discounting by focusing on the timing and demand rather than customer demographics. This approach allows businesses to adjust prices in real-time to attract customers during low-demand periods, optimize occupancy, and increase overall revenue, all while providing value to price-sensitive consumers (Figure 45).

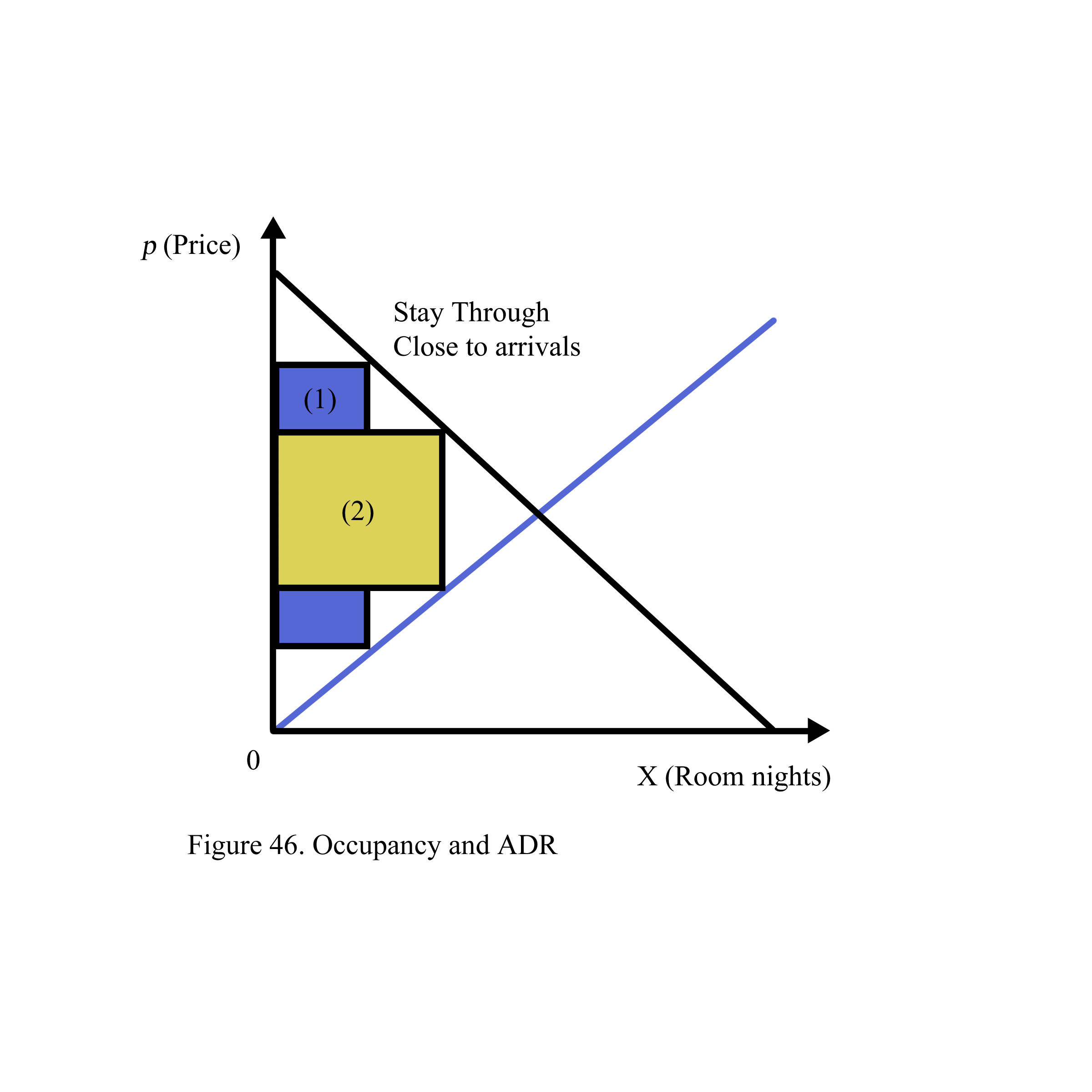

Stay (Duration) Control

Duration control is a strategic approach used in the hospitality industry to manage and optimize occupancy over multiple days by filtering out undesirable length-of-stay patterns. The primary goal of duration control is to ensure that a hotel or similar accommodation can maximize its occupancy and revenue across a specific period, rather than just focusing on individual nights. This involves selectively accepting or declining bookings based on the length of stay to avoid gaps in occupancy and to better align with periods of higher demand.

In essence, duration control helps hotels achieve a balanced and consistent occupancy rate by encouraging or discouraging certain booking patterns. For example, a hotel might avoid accepting one-night stays during a busy weekend if those short stays would prevent the hotel from booking longer, more profitable stays. Instead, the hotel could implement a minimum stay requirement, such as requiring guests to book at least two or three nights during a high-demand period like a holiday weekend or a major event. By doing so, the hotel can maximize its occupancy across multiple days and reduce the likelihood of unoccupied rooms on certain nights.

One of the key tactics of duration control is using pricing strategies to influence guests’ booking behavior. By adjusting room rates based on the length of stay, hotels can attract customers who are willing to stay longer, thereby filling rooms that might otherwise go vacant. For instance, a hotel might offer a lower nightly rate for guests who book a longer stay, such as a discount for staying three or more nights. This not only increases occupancy over a more extended period but also ensures a more stable revenue stream.

Conversely, during times when the hotel expects to receive high-end customers or during peak demand periods, duration control can be used to close or limit availability for shorter stays. For example, a hotel anticipating a surge in demand for a major conference or festival might restrict one-night bookings to ensure that rooms are available for guests who are willing to stay for the entire duration of the event. This approach allows the hotel to maximize revenue by catering to higher-paying customers who require longer stays.

Duration control also plays a critical role in managing revenue and profitability. By carefully controlling the length of stay, hotels can optimize their room inventory and pricing to ensure they are making the most of high-demand periods while avoiding low occupancy during off-peak times. This requires a deep understanding of booking patterns, market trends, and customer behavior, as well as the ability to adjust strategies in real-time based on changing conditions.

In addition to maximizing occupancy and revenue, duration control helps enhance the guest experience by ensuring that the hotel can accommodate guests for the entire duration of their stay, especially during high-demand periods. This can lead to higher guest satisfaction and loyalty, as guests appreciate the availability of rooms that meet their travel needs.

In summary, duration control is a strategic method used to manage and optimize hotel occupancy over multiple days by filtering out undesirable length-of-stay patterns. By using pricing strategies to influence guest behavior, hotels can attract longer stays or limit short stays to ensure they can accommodate high-end customers during peak demand periods. This approach not only maximizes occupancy and revenue but also enhances the overall guest experience and operational efficiency (Figure 46).

Close to Arrivals

“Close to arrival” is a restrictive pricing and booking strategy used by hotels to manage room availability and maximize revenue as the check-in date approaches. This tactic involves blocking or refusing all new arrivals for a specific date, regardless of the length of stay or the rate offered, in order to prioritize existing reservations or to accommodate larger, potentially more lucrative groups. The primary objective is to ensure that room inventory is reserved for high-priority bookings or significant events, rather than accepting individual reservations that might otherwise fill the remaining rooms.

This approach is often employed during periods of high demand or when a hotel is anticipating the arrival of large groups, conferences, or other high-profile events. By implementing a “close to arrival” restriction, hotels can effectively manage their inventory and revenue strategy, ensuring that they can accommodate these important groups and maximize their profitability.

For example, suppose a hotel has a significant group booking scheduled, such as Group B with 10 guests, and only 11 rooms are left available for a particular date. To prioritize this group and ensure they have the necessary accommodations, the hotel may choose to implement a “close to arrival” restriction. This means that no additional individual reservations will be accepted for that date, even if potential guests are willing to pay a high rate. As a result, the remaining room inventory becomes unavailable to other guests, effectively increasing the price of the remaining rooms due to their scarcity.

This pricing strategy can lead to a dramatic increase in rates for the remaining available rooms, as the hotel capitalizes on the high demand and limited availability. The higher rates are designed to maximize revenue from the remaining inventory, making it more profitable for the hotel while ensuring that the important group booking is accommodated without the risk of overbooking or conflicting reservations.

In practice, “close to arrival” restrictions can be used in conjunction with other pricing strategies, such as dynamic pricing or minimum stay requirements, to further optimize revenue and occupancy. By strategically managing room availability and pricing, hotels can balance the needs of high-priority groups with those of individual travelers, ensuring that they can maximize both occupancy and profitability.

Additionally, implementing a “close to arrival” restriction helps hotels manage operational efficiency and guest satisfaction. By ensuring that large groups have the rooms they need, hotels can reduce the risk of last-minute changes or disruptions, leading to a smoother check-in process and a more organized operation overall.

In summary, the “close to arrival” strategy is a restrictive approach used by hotels to prioritize large or important group bookings by refusing new reservations for a specific date. This tactic helps maximize revenue by increasing prices for the remaining available rooms and ensures that high-priority groups are accommodated as planned. By managing room inventory effectively, hotels can balance the needs of different types of guests, optimize occupancy, and enhance overall operational efficiency (Figure 47).

Cost Allocation

Cost allocation is a strategic approach used by businesses to prioritize and distribute their investments across different consumer segments based on their potential contribution to revenue maximization. This tactic involves analyzing various target groups to determine which segments offer the highest potential for generating revenue and then directing resources accordingly. The goal is to optimize financial performance by strategically investing in areas that will yield the greatest return.

Cost allocation involves several key steps:

Segment Analysis: Businesses first identify and analyze different consumer segments to understand their revenue potential. This includes evaluating factors such as purchasing power, frequency of purchases, profitability, and overall impact on the business’s financial goals.

Resource Distribution: Based on the analysis, businesses allocate their resources, such as marketing budgets, product development efforts, and sales strategies, to the segments that are most likely to contribute to revenue maximization. This ensures that investments are directed towards the areas with the highest potential for return.

Prioritization: Cost allocation helps businesses prioritize their investment efforts. For instance, a company might decide to invest more heavily in targeting high-value customers who make frequent purchases or have a high lifetime value, rather than spreading resources equally across all segments.

Game Theory Application: In the context of game scenarios, cost allocation can be seen as a strategic response to competitive pressures and market dynamics. It involves making informed decisions on where to place investments to gain a competitive edge and achieve optimal financial outcomes.

Example of Cost Allocation

Consider a hotel chain that wants to maximize its revenue across different market segments, including business travelers, leisure tourists, and group bookings. The hotel chain uses cost allocation to strategically invest in various areas to appeal to these segments.

Segment Analysis:

Business Travelers: This segment is characterized by frequent stays, high average daily rates (ADR), and lower price sensitivity. Business travelers often book during weekdays and may require amenities such as meeting rooms and high-speed internet.

Leisure Tourists: This segment includes families and couples who travel during weekends and vacation periods. They are more price-sensitive and look for special packages or discounts.

Group Bookings: This segment includes corporate events, conferences, or large family reunions. Group bookings can bring in significant revenue but require careful coordination and customized services.

Resource Distribution:

Business Travelers: The hotel chain allocates a substantial portion of its marketing budget to target business travelers through digital advertising on professional networks like LinkedIn, offering tailored business packages, and investing in high-quality amenities that appeal to this segment.

Leisure Tourists: To attract leisure tourists, the hotel chain invests in seasonal promotions, family-friendly packages, and partnerships with local attractions. They also enhance their online presence with appealing offers on travel websites.

Group Bookings: The hotel chain allocates resources to develop specialized group packages, improve event management capabilities, and offer incentives for large bookings. They also invest in relationship-building with event planners and corporate clients.

Prioritization:

Given the higher revenue potential and frequency of business travelers, the hotel chain prioritizes investments that cater to this segment, such as upgrading meeting facilities and improving business services. However, they also ensure that leisure tourists and group bookings are not neglected by maintaining a balanced approach.

Game Theory Application:

In response to competitive pressures, the hotel chain uses cost allocation to stay ahead of competitors. For example, if a rival hotel chain is aggressively targeting business travelers, the hotel chain might increase its investment in premium business services and loyalty programs to retain and attract this segment.

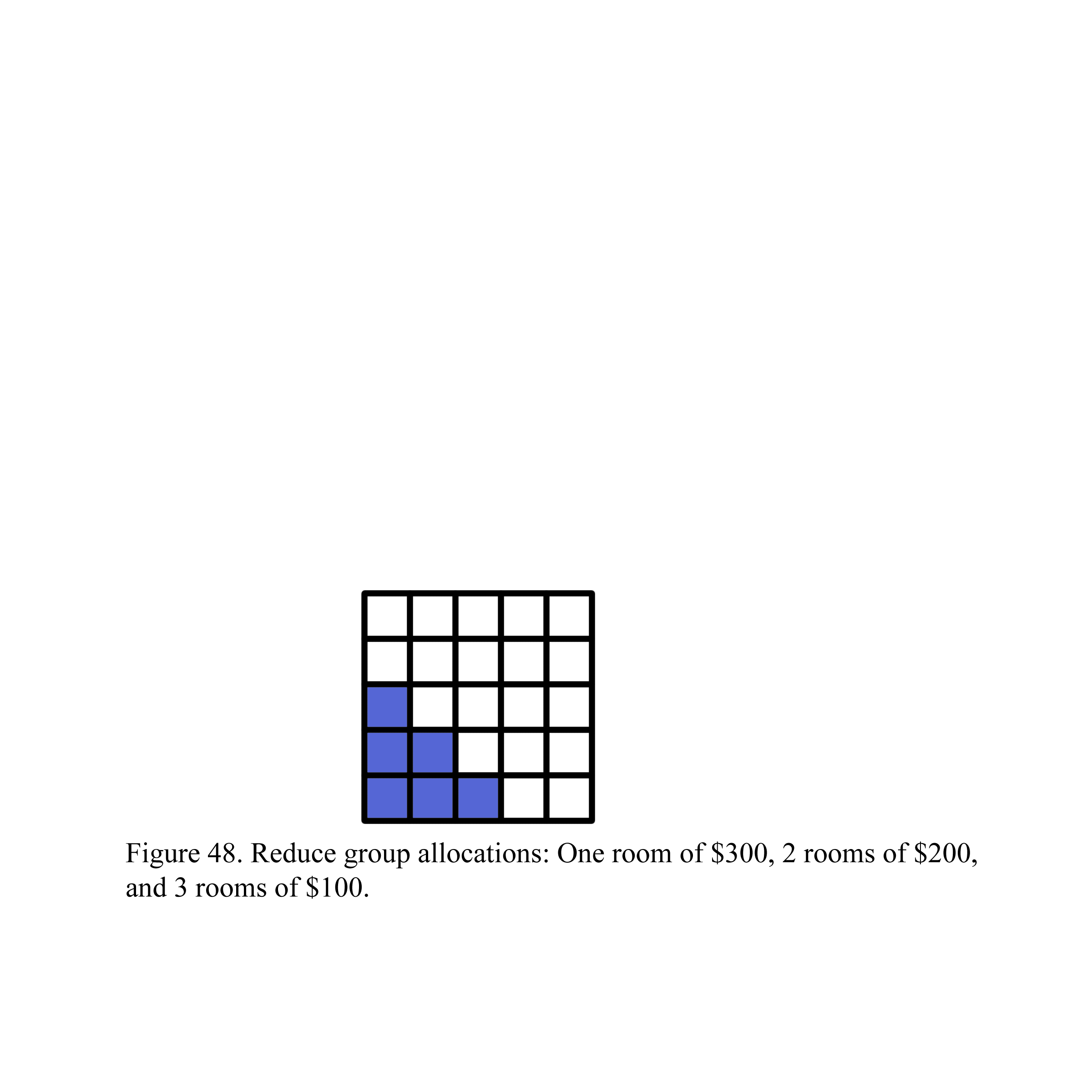

By effectively implementing cost allocation, the hotel chain optimizes its investments, enhances its competitive position, and maximizes its overall revenue potential. This strategic approach ensures that resources are used efficiently and that the most lucrative customer segments receive the attention they deserve (Figure 48).

Discount

Discounting is a pricing strategy used by businesses to offer reduced rates or special deals to certain customers based on various factors, including their spending behavior, loyalty, or specific demographics. Discounts can take several forms and are typically used to attract or reward customers, encourage repeat business, or manage demand. Here’s an expanded look at how discounting works, including examples:

Types of Discounts

Spending-Based Discounts:

Discounts can be offered based on the customer’s spending behavior. For example, in a hotel with a casino, guests who engage in high levels of gambling might receive discounts on their hotel room rates. This is a form of reward for their additional expenditure and aims to incentivize continued spending. Similarly, guests who spend a significant amount on food and beverages at hotel restaurants might be given a discount on their next stay or on additional services.

Example: A hotel guest who gambles $500 in the casino might receive a 20% discount on their room rate for their next visit. This encourages higher spending at the casino and increases overall revenue.

Product Mix Discounts:

These discounts are applied to specific combinations of products or services. Businesses often use product mix discounts to encourage customers to purchase a broader range of offerings or to increase the average transaction value.

Example: A hotel might offer a discounted package that includes a room, breakfast, and a spa treatment. This discounted bundle is priced lower than if each service were purchased separately, enticing guests to take advantage of the combined offer.

Time-Based Discounts:

Time-based discounts are offered during specific periods to manage demand, increase occupancy, or stimulate sales. These discounts are often used during off-peak times or when there is a need to fill available slots.

Example: A hotel might implement a time-based discount from 2 PM to 5 PM, offering reduced rates for guests who check in during this period. This helps manage check-in flow and increases occupancy during times when demand is typically lower.

Tactical Discounting

Tactical discounting involves offering discounts to specific groups based on their characteristics or affiliations. This strategy aims to attract or reward certain customer segments by providing them with special rates or offers.

Demographic-Based Discounts:

Tactical discounting is commonly used to offer reduced rates to groups such as military personnel, seniors, or children. These discounts are often seen as a way to acknowledge and reward these groups for their service, age, or family status.

Example: A hotel might offer a 10% discount to military veterans and active-duty personnel as a gesture of appreciation. Similarly, seniors over the age of 65 might receive a discount on their room rates, or families with children might benefit from reduced prices on family packages.

Loyalty and Reward Discounts:

Tactical discounting can also include loyalty programs where frequent customers receive special discounts or benefits as a reward for their continued patronage. These discounts help build customer loyalty and encourage repeat business.

Example: A hotel chain might offer a loyalty program where frequent guests earn points for each stay. Once a certain threshold is reached, guests can redeem points for discounts on future stays or receive complimentary upgrades.

Promotional Discounts:

Promotional discounts are used to drive traffic during specific campaigns or events. These discounts might be targeted at specific customer segments based on current promotions or seasonal offers.

Example: During a special promotional period, a hotel might offer a 15% discount to guests who book a stay through a particular travel website or social media platform. This tactic aims to increase bookings during the promotional period and attract customers from specific channels.

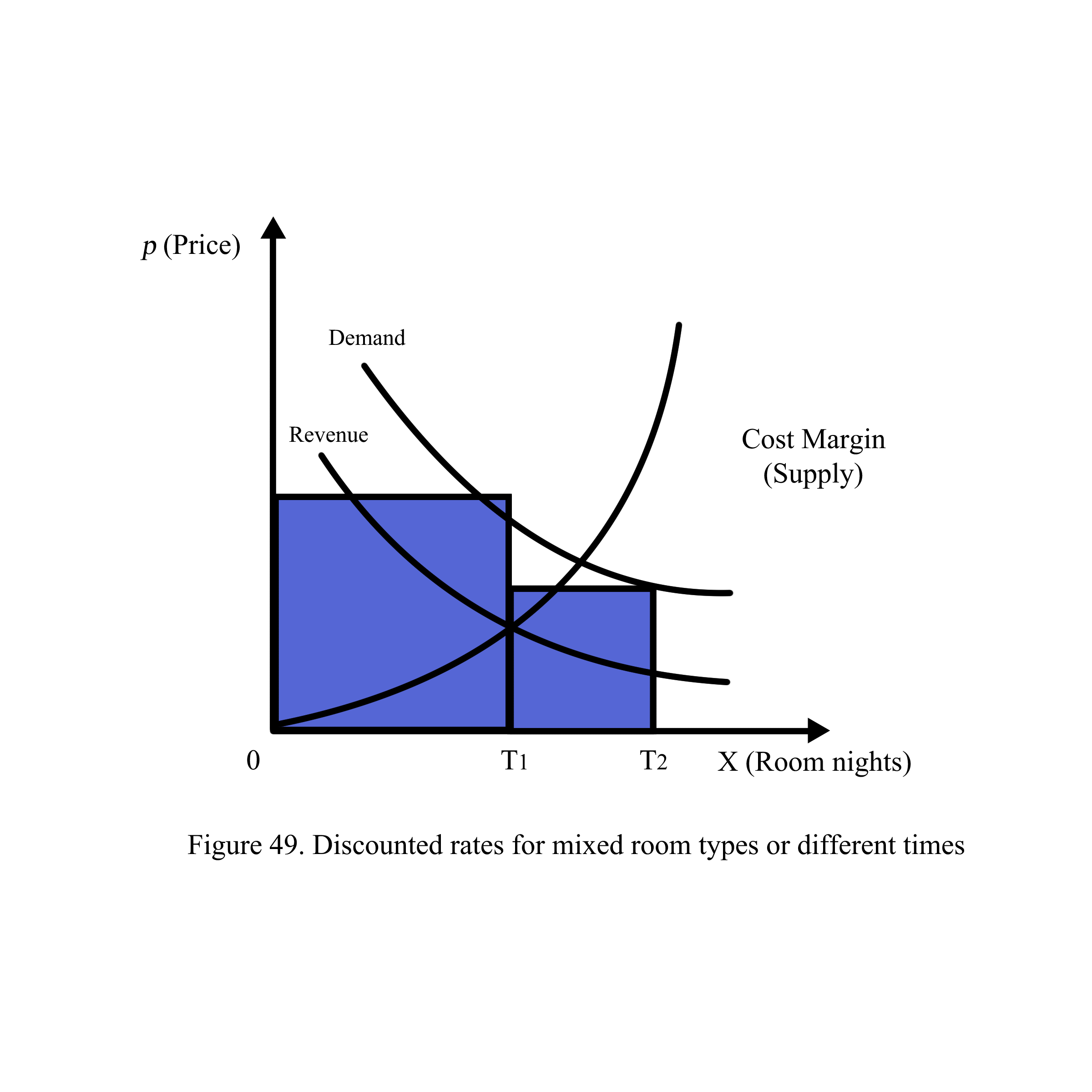

Summary

Discounting is a versatile tool used by businesses to enhance customer satisfaction, stimulate demand, and optimize revenue. By applying discounts based on spending behavior, product mix, time periods, and specific customer demographics, businesses can effectively manage their pricing strategy and appeal to a wide range of customers. Tactical discounting, in particular, focuses on providing targeted offers to special groups such as military personnel, seniors, or frequent guests, rewarding them for their patronage and encouraging continued engagement (Figure 49).

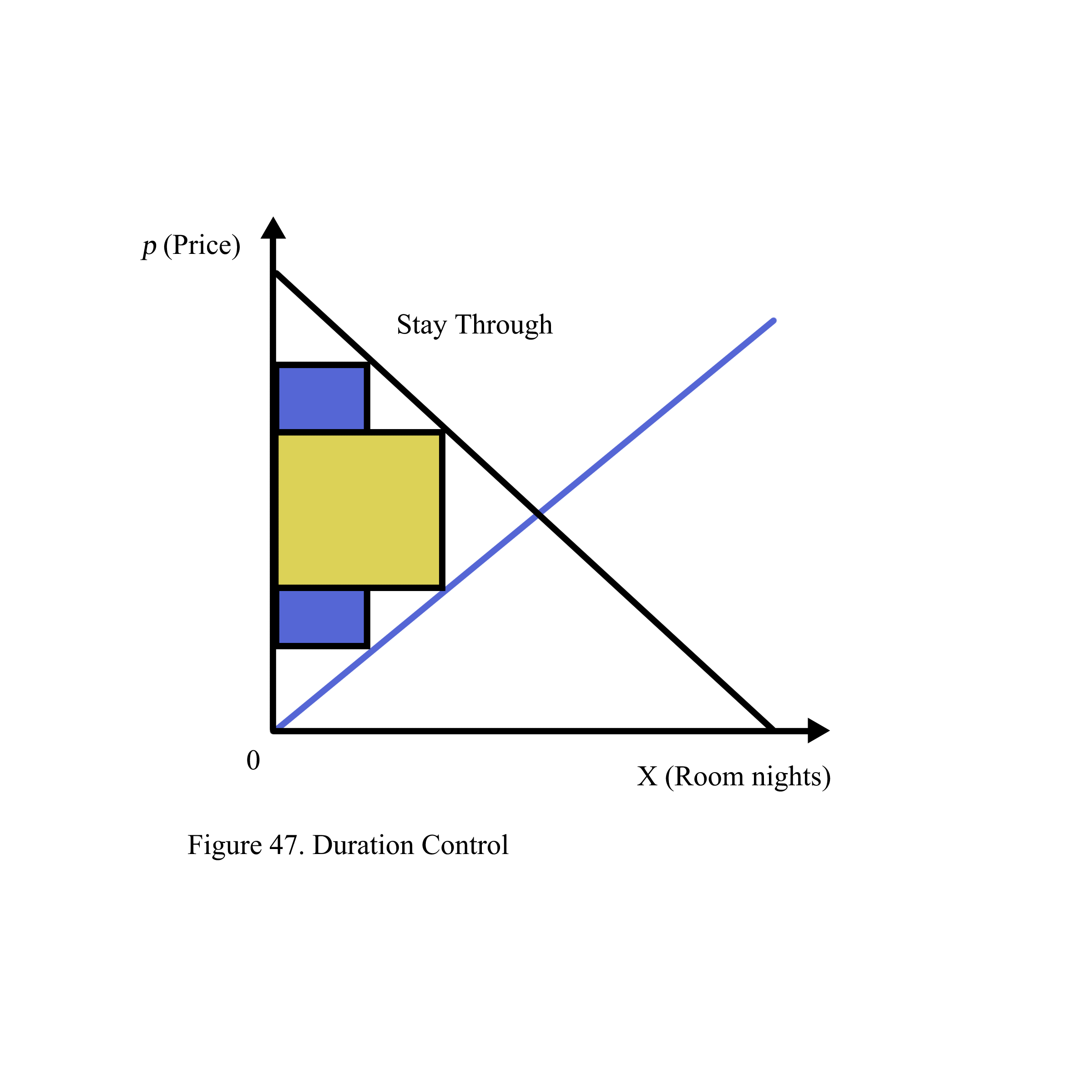

11. Duration Control

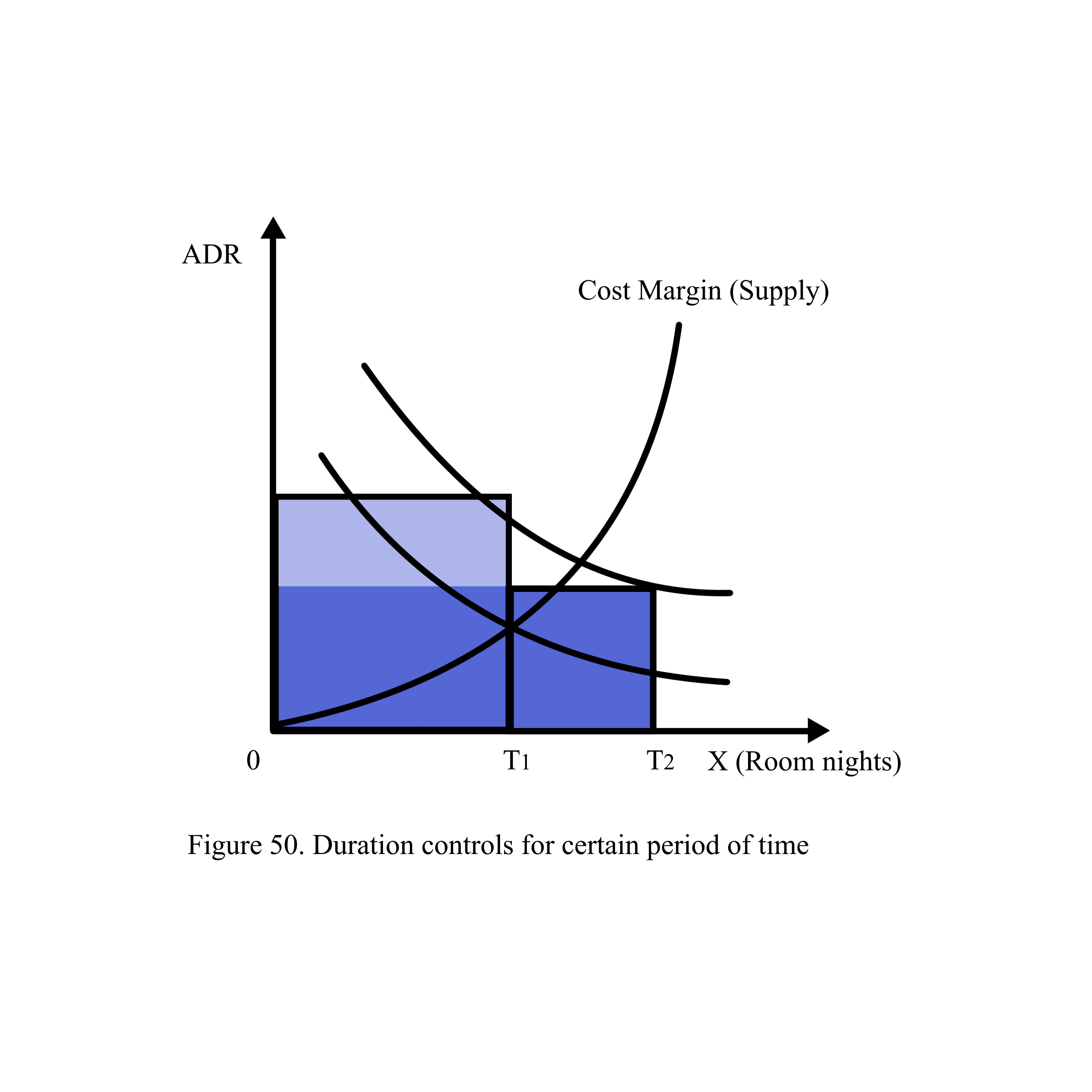

Duration control in hotel revenue management involves applying time constraints on reservations to ensure that room availability aligns with the hotel’s overall revenue goals. The primary purpose is to protect inventory for higher-value, multi-day bookings, especially during periods of high demand. In practice, this means that the hotel might reject or restrict one-night stays if accepting them would limit the opportunity to sell rooms for more lucrative, longer stays. Hotels aim to maximize revenue by ensuring that rooms are occupied by guests who will generate the highest possible income. Duration control helps protect room availability for multi-night stays, which are often more profitable compared to single-night bookings. This is especially important when a one-night stay may prevent the hotel from selling the same room for a longer period during peak demand. When a hotel expects high demand over several consecutive days (e.g., during a conference, holiday, or major event), it may implement minimum length of stay (MLOS) restrictions. This ensures that the hotel doesn’t lose out on guests who need rooms for multiple nights, as a single-night booking might otherwise block part of a longer, more valuable reservation. Hotels might reject or limit one-night stays, especially during periods where multi-day reservations are more common and desirable. For example, during a busy weekend or event, a hotel might turn down a one-night Friday booking if it expects to sell the same room to a guest who wants to stay Friday through Sunday. This allows the hotel to maximize occupancy and revenue over the entire duration of high demand. The ultimate goal of duration control is to increase RevPAR, a key performance metric in hotel revenue management. By applying restrictions on shorter stays and prioritizing longer, more profitable bookings, hotels can better balance their room inventory and pricing strategies to maximize total revenue. Imagine a hotel expects high demand over a long weekend due to a local festival. The hotel anticipates that most guests will want to stay for 3 nights (Friday to Sunday). If the hotel allows one-night stays on Friday, it could prevent potential bookings for the entire weekend, limiting overall revenue. By applying duration control, the hotel might require a minimum stay of 2 or 3 nights, ensuring that the available rooms are reserved by guests staying the entire weekend. This strategy maximizes both occupancy and revenue during high-demand periods.

In this way, duration control effectively manages the balance between occupancy and revenue, ensuring the hotel captures the highest possible value from its available room inventory (Figure 50)

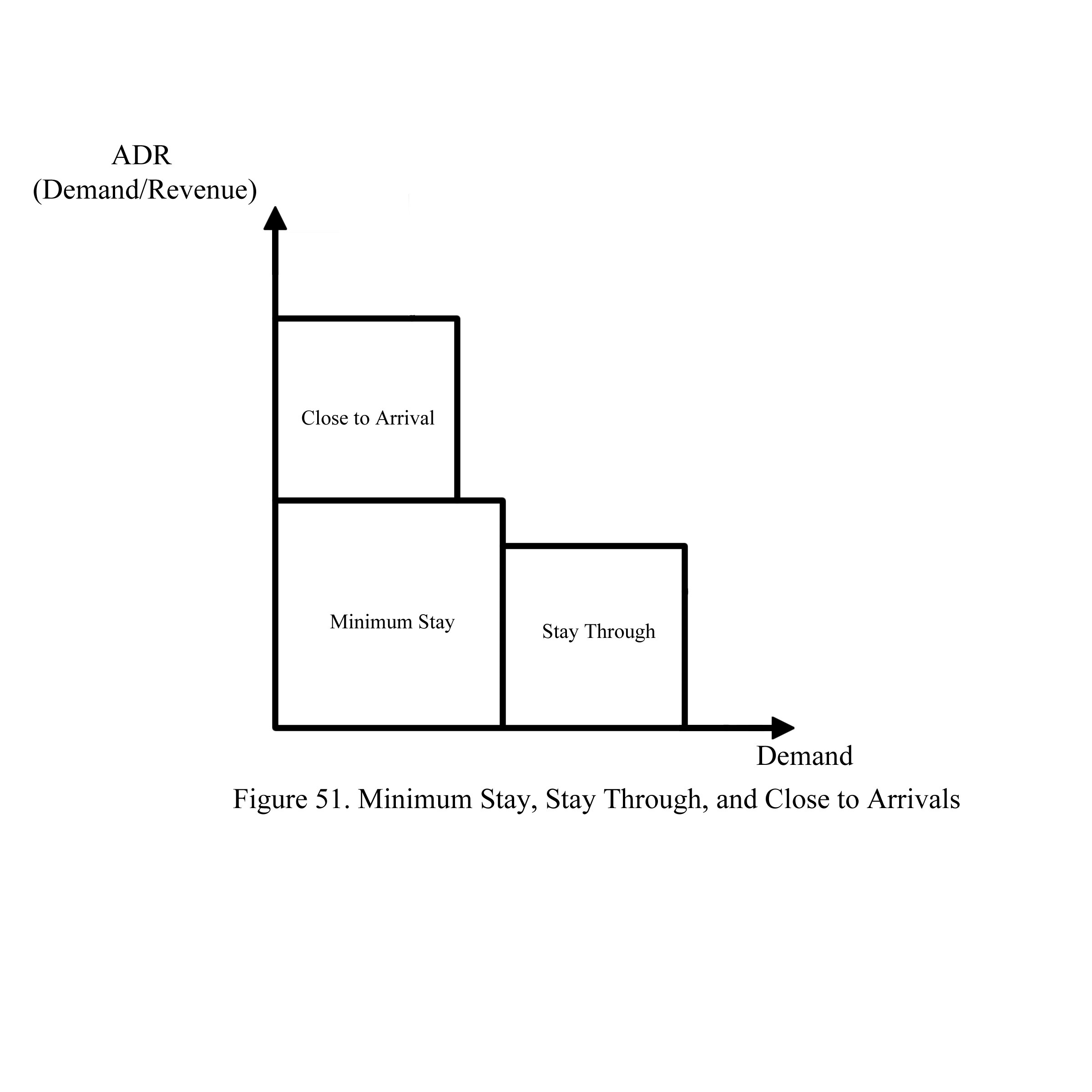

Minimum stay is a time that a hotel must make a guest stay one or more days in order for it to have an equal or good payout. A minimum stay is a policy set by a hotel that requires guests to book a room for a certain number of consecutive nights as a condition for making a reservation. Hotels often face periods of high demand, such as weekends, holidays, special events, or busy tourist seasons. During these times, there is a significant opportunity to increase revenue. By setting a minimum stay requirement (e.g., 2 or 3 nights), hotels can avoid filling up rooms with shorter stays that may leave gaps in occupancy, ensuring they capture more revenue over the full period of high demand. If a hotel allows guests to book single-night stays during high-demand periods, it may result in a lower overall room utilization. For example, a one-night stay on a Friday during a long weekend could prevent the hotel from selling that room to someone who wants to stay for the entire weekend. By imposing a minimum stay requirement, the hotel protects its room inventory, ensuring it can accommodate guests who are likely to pay for multiple nights, thus increasing the total revenue from each booking. Minimum stay restrictions also help hotels manage their occupancy patterns more effectively. By encouraging guests to book longer stays, hotels can smooth out fluctuations in room occupancy across several days. This is particularly important during peak seasons when shorter stays can create a disjointed booking pattern, leaving rooms empty for parts of the day or week that are harder to fill. For example, a two-night minimum stay might encourage weekend guests to check in earlier or stay later, filling mid-week gaps that are harder to sell. High-value guests, such as those attending conferences, festivals, or sporting events, often require multiple-night stays. If a hotel accepts too many one-night bookings during these periods, it could lose the opportunity to accommodate higher-paying guests who want to stay for the entire event. By implementing minimum stay restrictions, hotels ensure they capture the full revenue potential of high-value guests and avoid low-yield bookings that block room availability. Suppose a beachfront hotel is located in a popular vacation destination where demand peaks during holiday weekends and summer months. To make the most of the high demand, the hotel implements a 3-night minimum stay requirement over long weekends, such as Labor Day. This ensures that the hotel is not booked for only one night by guests looking for a quick getaway but rather captures the full value of guests staying for the entire holiday period. By doing so, the hotel not only boosts revenue but also optimizes its staffing, housekeeping, and operational efficiency since longer stays result in fewer turnovers and more stable occupancy. Fewer room turnovers reduce housekeeping and operational costs, as the hotel does not need to clean and prepare rooms as frequently. Minimum stay policies help create a more balanced flow of occupancy, avoiding gaps and optimizing room usage. (Figure 51).

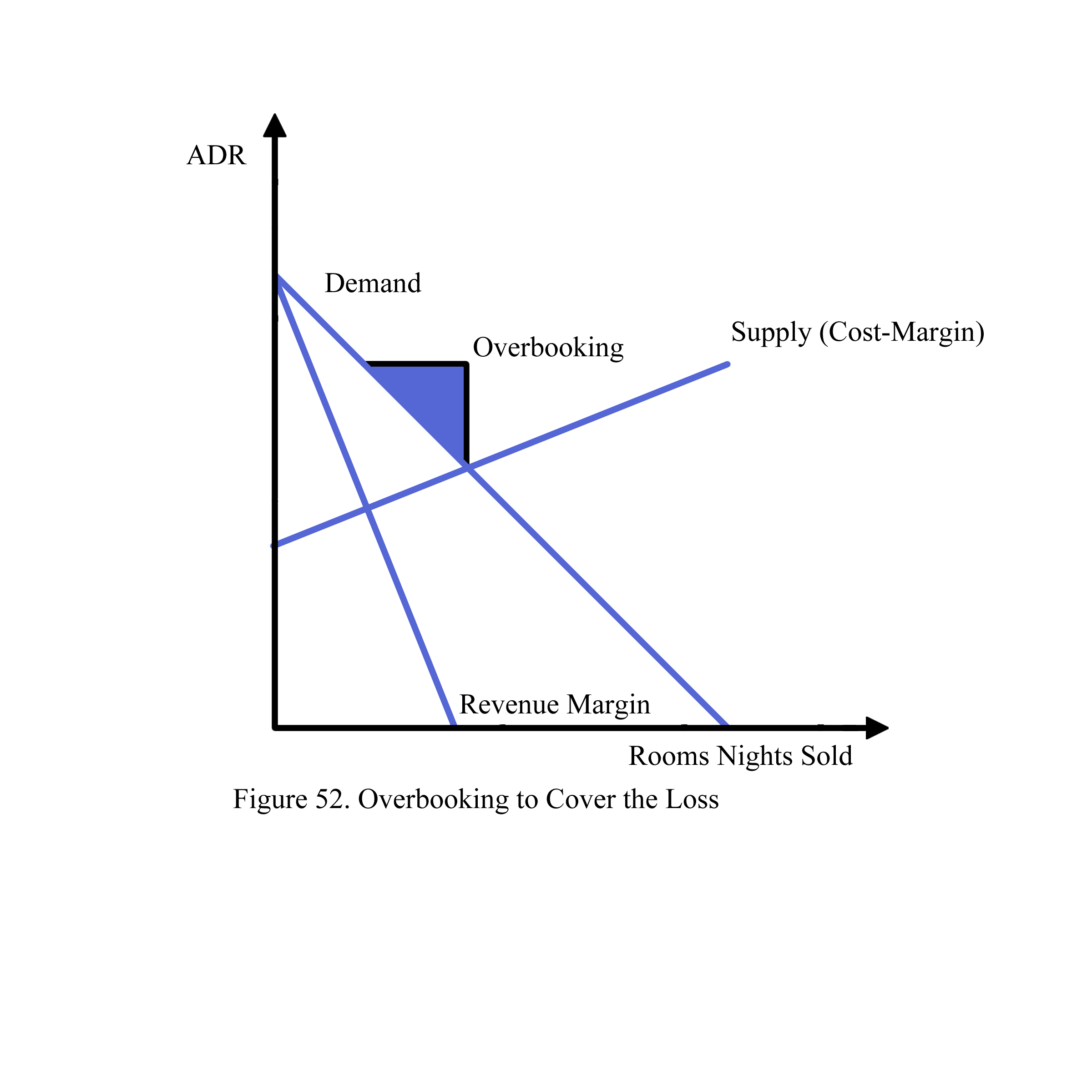

12. Capacity management

In hotel revenue management capacity management refers to the process of controlling and optimizing room inventory to maximize occupancy and revenue. This strategy involves managing the supply of available rooms while accounting for various factors that can affect actual demand. These factors include early check-outs, cancellations, no-shows, room spoilage (where rooms remain unoccupied after the hotel has stopped taking reservations), and group attrition (when fewer guests attend a group booking than originally anticipated). Early check-outs reduce expected occupancy, leaving rooms vacant for the remainder of the originally booked period. Guests may cancel their reservations, sometimes at the last minute. Without proper capacity management, this can result in unsold rooms and lost revenue. No-shows create the same issue as cancellations—rooms remain unoccupied, leading to lost revenue. To mitigate this, hotels may overbook or implement policies like non-refundable deposits to cover the cost of no-shows. Room spoilage occurs when a hotel keeps rooms unoccupied despite having the potential to sell them. This often happens when a hotel closes room availability too early, thinking it will reach full capacity, but cancellations or no-shows cause the rooms to remain vacant. Group bookings, such as conferences or weddings, can lead to group attrition when fewer guests arrive than initially booked. In group bookings, spill-over refers to the number of rooms reserved in the group block that are not occupied by group members, often due to late bookings or changes in plans. After a certain cut-off date, rooms not claimed by group members are released back into the general inventory. The wash factor represents the proportion of group members who check out earlier than the entire length of the event. This can lead to a higher-than-expected number of vacant rooms toward the end of an event. Hotels need to account for this when setting room block sizes and planning staffing and operational needs. One of the most common strategies used in capacity management is overbooking, which involves accepting more reservations than there are available rooms. This is done to compensate for the expected loss from early check-outs, cancellations, and no-shows. By overbooking, hotels aim to fill rooms that would otherwise go unoccupied due to these factors, thereby maximizing occupancy and revenue. In cases where too many guests arrive and the hotel is overbooked, some guests may need to be “walked” to a nearby hotel. While this can be inconvenient for the guest, hotels often compensate by covering the cost of the alternative accommodation and offering future discounts or perks (Figure 52).

The policy of meeting only those who stay in approved hotels is often used by event organizers to incentivize attendees or participants to stay at hotels that are part of a preferred or contracted group. Many large events such as conferences, conventions, or sports tournaments have partnerships with specific hotels. These hotels may offer financial kickbacks or reduced venue costs to the event organizer based on the number of rooms filled. If attendees stay elsewhere, it can reduce these benefits, so organizers encourage participants to book only at approved hotels. Organizers can more easily coordinate logistics, such as transportation or shuttle services, when attendees are concentrated in specific, approved hotels. By ensuring that all participants stay in approved hotels, organizers have better oversight of where attendees are staying, which can be important for safety, security, or compliance reasons, especially for corporate or government-related events.

The policy of no transportation for those who do not stay in hotels is designed to encourage event participants or group members to stay in specific hotels by restricting transportation services (such as shuttles or buses) only to those who have booked accommodations at designated properties. When attendees are provided with free or subsidized transportation, they are more likely to choose to stay at hotels approved by the event organizers. By limiting transportation to only those staying in designated hotels, the organizer can reduce transportation costs by limiting the scope of the service. By concentrating guests in a smaller number of approved hotels, transportation can be streamlined, reducing delays, travel time, and logistical confusion.

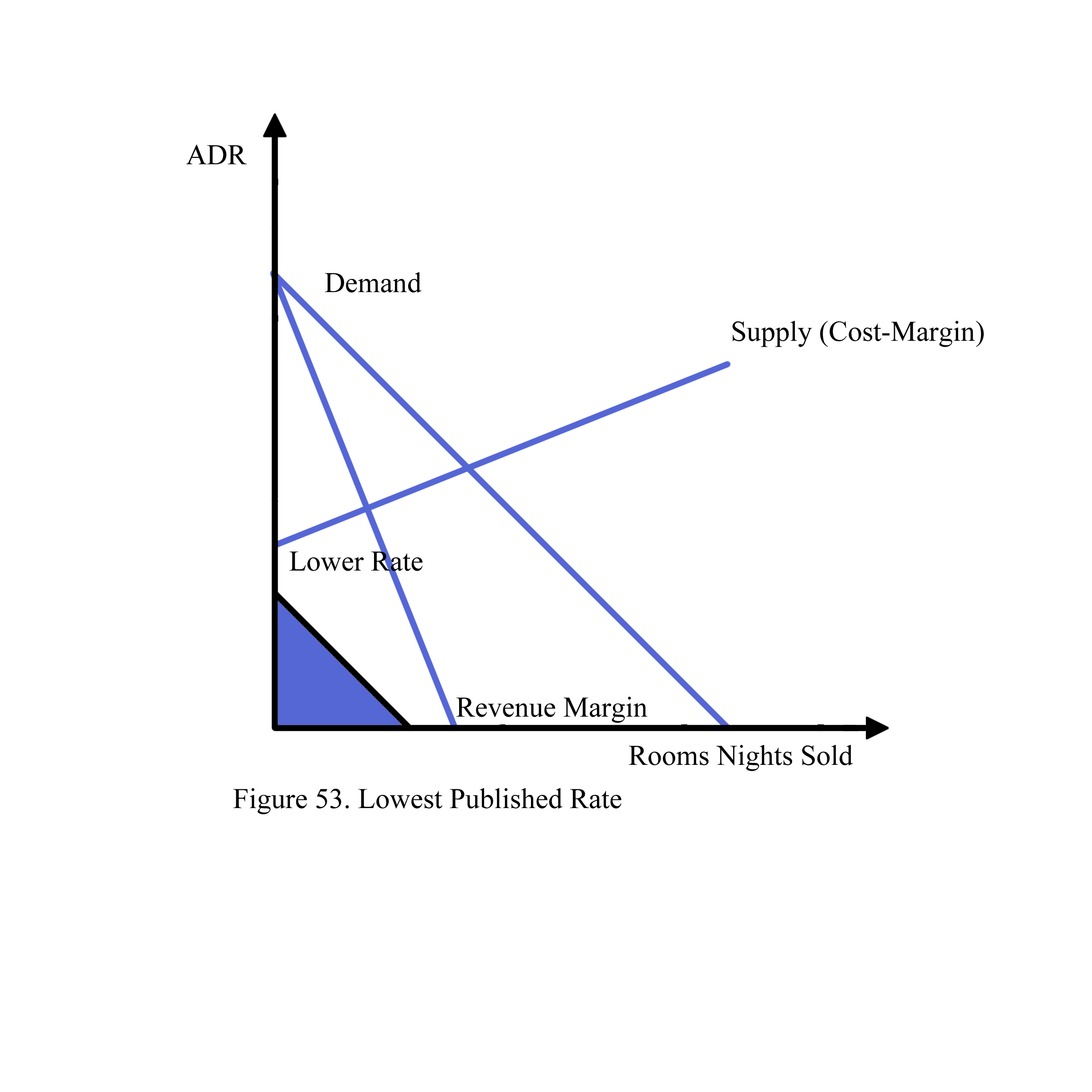

The policy of the lowest published rate for hotels’ discount rates ensures that guests booking under a group or event block are getting the best possible deal, thereby encouraging them to book within the block rather than searching for lower rates elsewhere. When event attendees or group members are assured they’re receiving the lowest rate available, they are more likely to book rooms within the designated block, ensuring the group or event meets its room quota requirements. Offering the “lowest published rate” ensures that attendees book through the designated block, preventing revenue leakage for both the organizer and the hotel. Offering the lowest published rate incentivizes attendees to stay within the group block, helping organizers meet their commitments and avoid additional costs. (Figure 53).

13. Displacement analysis

In hotel revenue management displacement is used to determine whether accepting a particular group or booking will result in a loss of more profitable individual bookings. It involves weighing the potential revenue of a group booking or discounted rate against the revenue that could be earned from regular guests during the same period. By analyzing both inelastic and elastic demand scenarios, hoteliers can make informed decisions about pricing and booking strategies.

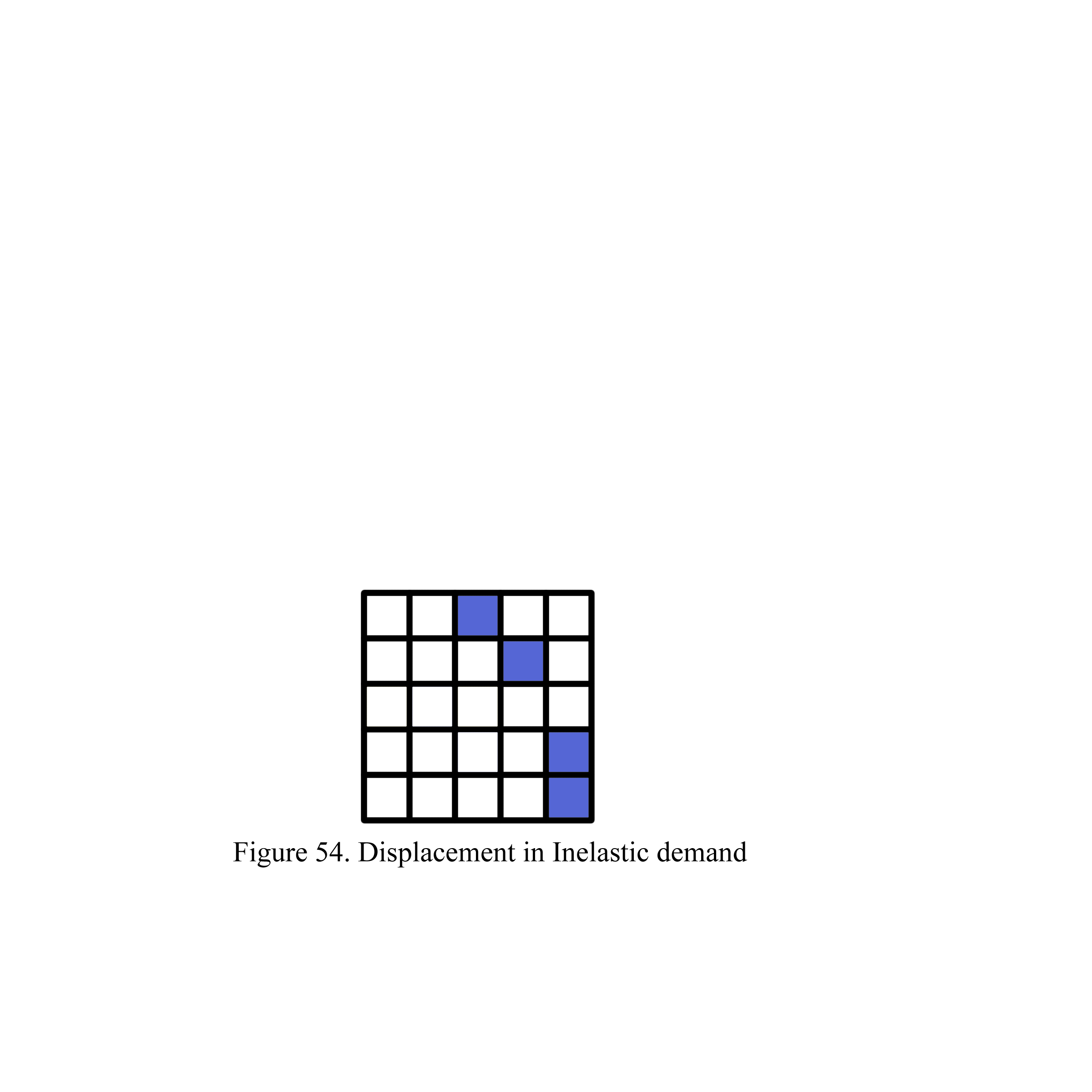

13.1 Inelastic Demand and Revenue Margin

Inelastic demand refers to a situation where customer demand for a service or product remains relatively unchanged despite fluctuations in price. In the context of the hotel industry, inelastic demand occurs when guests are willing to pay higher rates because their need for accommodations is so strong that price changes do not significantly affect their booking decision. This is typical during periods of high demand, such as during major events, holidays, or peak tourist seasons. Revenue Margin refers to the change in a hotel’s revenue resulting from price adjustments. In periods of inelastic demand, hoteliers can increase room rates without risking a significant drop in bookings. As occupancy rates rise and the hotel reaches near-full capacity, the revenue margin improves because guests are less sensitive to price increases. For instance, if a hotel experiences an influx of guests due to a large convention or special event in the city, the hotel can raise room rates, knowing that many guests will still book despite the price hike. A beachfront hotel during a popular summer festival may experience inelastic demand. Guests attending the festival will need accommodations regardless of the price increase, so the hotel can raise rates by 15-20% to maximize its revenue. Since guests are unlikely to find alternative accommodations during such a busy period, the demand remains stable, and the hotel’s revenue margin increases. Figure 54 illustrates the relationship between price increases and revenue during inelastic demand periods, showing how higher room rates lead to higher revenue without significantly reducing occupancy.

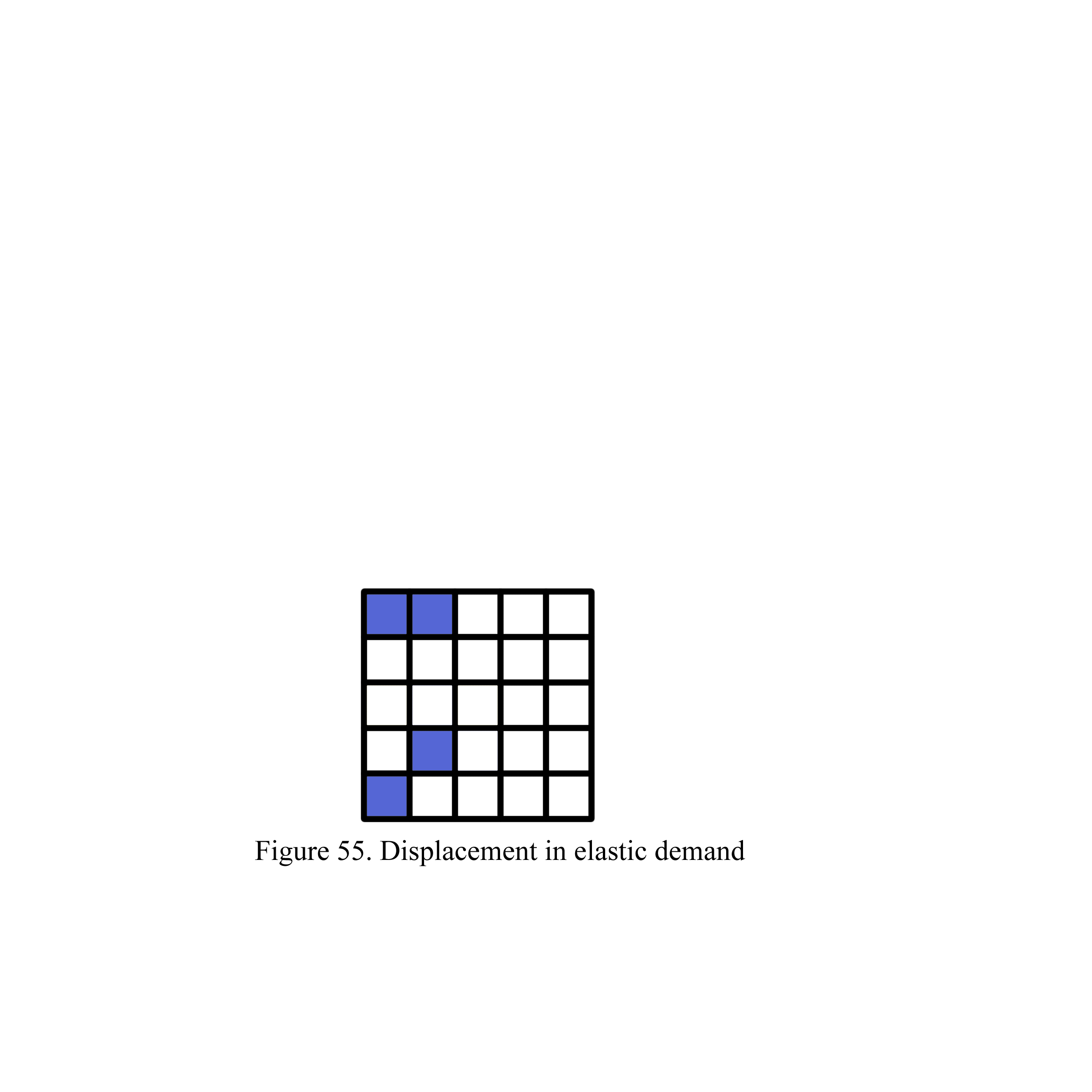

13.2 Elastic Demand and Revenue Margin

Elastic demand is the opposite of inelastic demand. In this scenario, small changes in price can significantly impact the decision of customers to book a room. When demand is elastic, guests are more price-sensitive, and even a slight increase in rates could lead to a significant drop in bookings. Hotels often face elastic demand during off-peak seasons, weekdays, or in highly competitive markets where guests have many alternative options. In periods of elastic demand, hotels need to be more cautious about raising prices, as doing so could lead to lower occupancy rates and, in turn, reduced overall revenue. To encourage bookings, hoteliers may need to lower prices or offer discounts to attract cost-sensitive guests. By reducing room rates, hotels can maintain or increase their occupancy levels, which helps sustain their overall revenue margin even during periods of lower demand. A city-center hotel in a business district might experience elastic demand during the weekend when business travelers are less likely to book. If the hotel raises prices, potential leisure travelers may choose cheaper accommodations, leading to lower occupancy. To avoid this, the hotel could lower rates by 10-15% during the weekend to attract more guests and keep rooms occupied. Figure 55 demonstrates how changes in pricing during periods of elastic demand directly affect occupancy rates and overall revenue, emphasizing the need to balance price and volume.

14. Hurdle Rate

The hurdle rate is the minimum acceptable rate a hotel is willing to offer for a room on a given day or week. It represents the lowest price at which a hotel can still cover its costs and generate a sufficient return. The hurdle rate takes into account both fixed and variable costs, such as housekeeping, utilities, taxes, and debt servicing. This concept helps hotels avoid selling rooms at a price that does not cover their operational expenses, ensuring that they achieve a minimum level of profitability. The hurdle rate serves as the breakeven point where the revenue from a room booking meets or exceeds the average cost of providing the room. If a hotel sets prices below the hurdle rate, it risks losing money on that booking. However, during periods of low demand, hotels may lower their prices to the hurdle rate or slightly above it to avoid having unsold rooms, which would result in zero revenue for those nights. A hotel calculates its hurdle rate based on the following costs: Housekeeping and room service: $80 (variable cost that can fluctuate depending on guest usage). Taxes and debt servicing: $60 (fixed cost). Total minimum cost: $140.

In this case, the hotel must set a minimum room rate of $140 to ensure that it covers both variable and fixed costs. If the hotel charges less than this amount, it will not generate enough revenue to break even, leading to a negative impact on the revenue margin.

Figure 56 illustrates the relationship between the hurdle rate, revenue margin, and average costs, showing the point at which a hotel can achieve profitability without undercutting its operational costs.

Key terms:

Discount: A reduction in the standard room rate offered to attract customers, increase occupancy, or compete with other hotels. Discounts can be applied in various ways, such as percentage off, fixed amount off, or special promotional rates. To encourage bookings, especially during low-demand periods or to attract specific customer segments.

Example: A hotel might offer a 20% discount on room rates for guests who book at least 30 days in advance.

Cost Allocation: The process of distributing costs associated with operating a hotel (such as utilities, staffing, and maintenance) across various departments or units to determine their impact on profitability. To understand the financial performance of different departments or services and to set appropriate pricing strategies. Costs are allocated based on criteria like usage, revenue generated, or space occupied by different departments or services.

Example: Allocating a portion of the hotel’s overall utility costs to each department (e.g., housekeeping, front desk) based on their energy consumption.

Close to Arrivals: A strategy to manage room inventory and pricing for reservations that are close to the arrival date. This involves making pricing and availability decisions based on the current booking situation and demand. To optimize revenue from last-minute bookings or manage availability as the arrival date approaches. Hotels may adjust prices or availability based on the remaining time until arrival and current occupancy levels.

Example: A hotel might offer discounted rates for rooms that are still available within a week of the arrival date to fill remaining inventory.

Stay Control: Techniques used to manage the length of guest stays, including setting minimum or maximum stay requirements. To optimize revenue by influencing booking patterns and ensuring efficient use of room inventory. Hotels may implement restrictions on the length of stay during peak times or offer incentives for longer stays during low periods.

Example: A hotel might require a minimum stay of 3 nights during a busy holiday season or offer discounts for extended stays during off-peak times.

Tactical Discounting: Strategic use of discounts to achieve specific short-term objectives, such as increasing occupancy, attracting specific customer segments, or responding to competitive pressures. To achieve targeted goals quickly and effectively through temporary price reductions. Discounts are applied based on current market conditions, competitive actions, or specific promotional goals.

Example: Offering a flash sale with a 25% discount for bookings made within the next 24 hours to drive immediate reservations.

Rate Structure: The framework for setting room rates, including the various rate categories, pricing rules, and how rates are adjusted based on factors such as demand, length of stay, and booking channels. To provide a clear pricing strategy that aligns with the hotel’s revenue management goals and market conditions. Rate structures may include standard rates, promotional rates, corporate rates, and seasonal rates.

Example: A hotel might have a rate structure that includes different rates for weekdays versus weekends, early booking discounts, and last-minute rates.

Duration Constrained: A pricing or inventory strategy that limits the length of stay that can be booked, typically to optimize occupancy and revenue. To manage inventory and maximize revenue by controlling the duration of stays. Hotels set restrictions on the minimum or maximum length of stay for certain periods or rates.

Example: A hotel might impose a maximum stay of 5 nights for promotional rates to ensure room availability for other potential bookings.

Capacity Constrained. A situation where the hotel’s available room inventory limits its ability to accommodate all demand. This constraint influences pricing and booking strategies. To manage revenue and occupancy effectively when the hotel’s capacity is fully utilized or nearly so. Pricing and inventory strategies are adjusted based on the hotel’s capacity limits to maximize revenue and manage demand.

Example: During high-demand periods, a hotel may increase rates significantly due to limited available rooms.

Constrained Demand. Demand that is limited by the hotel’s ability to provide rooms or services, often due to capacity or availability constraints. To address the limitations of demand that cannot be fully met due to restrictions in inventory or other resources. Revenue management strategies focus on maximizing revenue from the available inventory when demand is constrained.

Example: A hotel with limited rooms available during a major event might focus on optimizing pricing for the limited demand it can accommodate.

Unconstrained Demand. The total demand for hotel rooms without any limitations or restrictions imposed by the hotel’s capacity or availability. It represents the full potential demand if there were no constraints. To understand the maximum possible demand and guide strategic decisions for pricing and inventory management. By analyzing unconstrained demand, hotels can better estimate potential revenue and make informed decisions about capacity and pricing.

Example: If a hotel could theoretically sell 200 room nights but only has 100 available, the unconstrained demand is for 200 room nights.

Dynamic Pricing: Dynamic pricing involves adjusting room rates in real-time based on current market conditions, such as demand, availability, and competitor pricing. To maximize revenue by setting prices that reflect real-time market conditions. Prices may increase during high demand periods or decrease during low demand periods. Tools like revenue management systems (RMS) help automate these adjustments based on algorithms.

Example: A hotel might raise rates for rooms during a major local event when demand is high and lower them during off-season periods to attract more bookings.

Segmented Pricing: Segmenting pricing involves setting different rates for different customer groups based on their specific needs, preferences, or booking behaviors. To capture revenue from various customer segments by tailoring prices to their willingness to pay. Hotels may offer corporate rates for business travelers, advance purchase discounts for leisure travelers, or special rates for groups.

Example: A hotel might charge higher rates for flexible, last-minute bookings and offer discounted rates for guests who book months in advance.

Forecasting. Forecasting is the process of predicting future demand based on historical data, market trends, and booking patterns. To make informed decisions about pricing and inventory management to optimize revenue. Revenue management systems analyze past booking data, local events, seasonal trends, and other variables to forecast future demand.

Example: A hotel might use historical occupancy data and upcoming local events to predict higher demand and adjust prices accordingly.

Inventory Control: Inventory control involves managing the availability of rooms to maximize revenue. This can include strategies like restricting availability for discounted rates or managing room types. To ensure that rooms are allocated in a way that maximizes revenue and occupancy. Hotels may set limits on the number of rooms available at discount rates or control the release of room types based on demand.

Example: A hotel might hold back a portion of rooms from online travel agencies (OTAs) to sell directly at higher rates.

Overbooking: Overbooking is the practice of accepting more reservations than there are available rooms to compensate for expected cancellations and no-shows. To maximize occupancy and revenue by reducing the impact of cancellations and no-shows. Hotels use historical data and forecasting to determine the optimal overbooking levels and manage potential overbookings through compensation or relocation strategies.

Example: A hotel might overbook by 5% based on historical no-show rates, ensuring that even if some guests do not show up, the hotel remains fully occupied.

Revenue Optimization: Revenue optimization involves strategies and tactics to maximize the total revenue generated from room sales and other hotel services. To achieve the highest possible revenue by balancing pricing, occupancy, and inventory. This includes implementing dynamic pricing, adjusting room availability, and utilizing forecasting to make data-driven decisions.

Example: A hotel might use a combination of high rates during peak periods and promotional discounts during low periods to optimize overall revenue.

Length of Stay (LOS) Controls: Length of Stay controls are strategies that manage the minimum or maximum length of stay requirements to optimize occupancy and revenue. To influence booking patterns and ensure that room inventory is utilized efficiently. Hotels might impose minimum stay requirements during peak periods or allow shorter stays during low periods.

Example: A hotel might require a minimum stay of 3 nights during a major local festival to maximize revenue, while allowing one-night stays during quieter periods.

Rate Parity: Rate parity ensures that the room rates are consistent across all distribution channels, including direct bookings and third-party sites. To prevent rate discrepancies that could lead to customer dissatisfaction or loss of bookings through specific channels. Hotels use rate parity agreements and tools to ensure that rates offered on OTAs, hotel websites, and other booking platforms are the same.

Example: A hotel ensures that its room rates on its own website are the same as those listed on OTAs like Booking.com and Expedia.

Upselling and Cross-Selling: Upselling involves encouraging customers to purchase a more expensive room or upgrade, while cross-selling involves offering additional services or amenities. To increase revenue per booking by enhancing the customer experience and offering value-added options. Hotels might offer room upgrades, premium packages, or additional services like spa treatments or dining experiences.

Example: During check-in, a guest might be offered a suite upgrade for an additional fee or a package that includes breakfast and parking.

Competitive Pricing: Competitive pricing involves setting room rates based on the rates charged by competing hotels in the same market. To remain competitive and attract customers while maximizing revenue. Hotels monitor competitors’ prices and adjust their own rates to remain attractive while ensuring profitability.

Example: A hotel might adjust its rates based on the pricing of nearby hotels with similar amenities and location to attract more bookings.

Minimum Stay Requirements: Minimum stay requirements involve setting a minimum number of nights a guest must book to make a reservation. To maximize revenue during peak periods or special events by ensuring longer stays. Hotels may impose minimum stay requirements during high-demand periods to increase average length of stay and revenue.

Example: A hotel might require a minimum stay of 3 nights during a local festival to ensure higher occupancy and revenue.

Inelastic Demand: Price increases during high-demand periods lead to higher revenue without significantly reducing occupancy. Hotels can capitalize on this by raising room rates, especially during events or peak seasons.

Elastic Demand: During low-demand periods, small price increases can lead to a drop in bookings. To maintain occupancy, hotels should lower prices or offer discounts, keeping rooms filled and preserving overall revenue.

Hurdle Rate: This is the minimum rate a hotel must charge to cover its costs and achieve profitability. Hotels use the hurdle rate as a baseline for pricing decisions, ensuring that they do not sell rooms below a certain price threshold, even during low-demand periods.

Review Questions:

- When raising rates to be consistent with competitors, draw graphs that show (1) the average and the other two marginal costs of the comp set, (2) raise rates to packages, (3) closed to arrivals, (4) sell through, and (5) minimized early departure.

- Draw graphs to show (1) discounts for those who book longer stays, (2) restrict bookings for shorter stays or minimum length of stay restrictions, and (3) Reduce or eliminate 6:00PM holds by tightening guarantee and cancellation policies

- Draw graphs to show (1) reassign room inventory, (2) sell to price-sensitive groups when occupancy is low, (3) spill over, and (4) wash factor.